A little history of libraries and why they matter

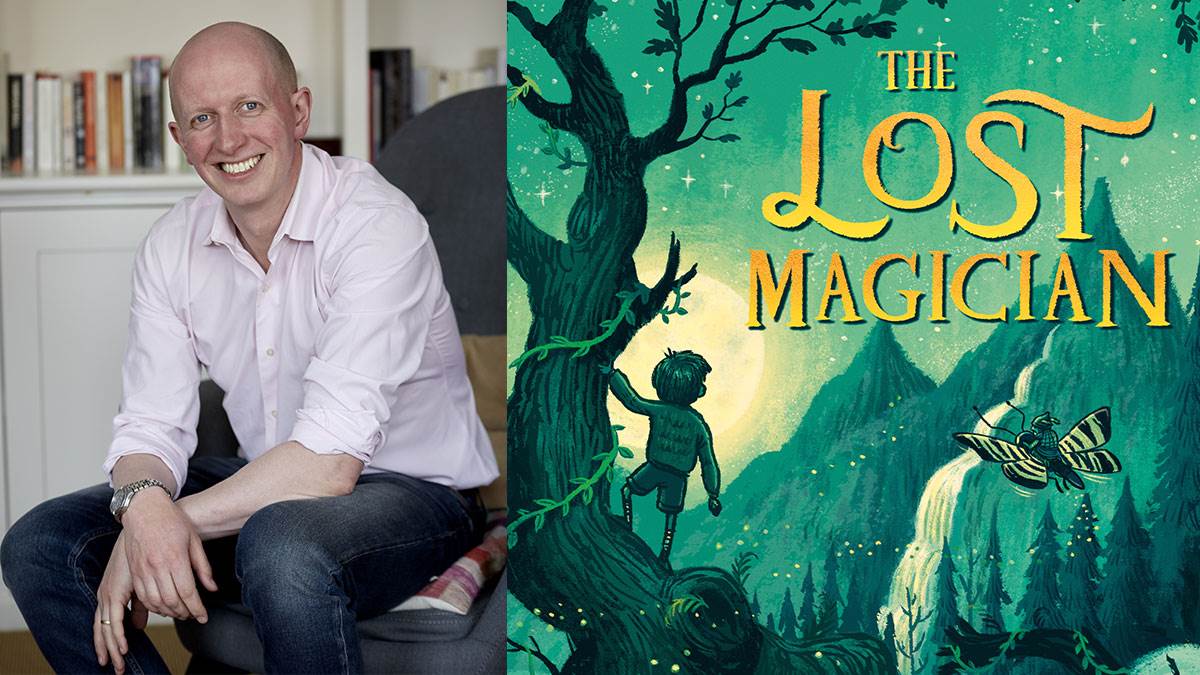

Published on: 25 September 2018 Author: Piers Torday

Author Piers Torday explains why libraries are so important for these times and our children, when the world needs a little more magic.

The books, to begin with, were chained to the bookcase. There were just 24 wooden stools for seating. For well over the first 100 years of its existence, there wasn’t even a list of the books. But it was, most definitely, a public library.

Chetham’s Library in Manchester, founded in 1653, is the oldest surviving public library in Britain. It was built with the legacy of a local textile merchant, Humphrey Chetham, who stated in his will that all future librarians ‘should require nothing of any man that cometh into the library’.

And that remains the same today – for any man, woman and, crucially, child.

Nothing required.

For me that is the essence of a library, and why I love them.

You don’t have to pay to come in. You don’t have to buy anything. You don’t even have to read, if you don’t want to. You can go just to think, or to be quiet. You can study and work there. For some, a library might feel safer than their home, school or workplace.

Libraries: spreading goodness everywhere

From the oak-panelled Chetham’s Library to the latest state-of-the-art library in China, libraries are not just buildings. They are powerful physical symbols of a culture’s belief in the value of shared civic space for all, the right to free thought and expression, and the organisation and distribution of knowledge for the public good.

In fact, “good” is the word I associate with libraries the most. The celebrated Andrew Carnegie founded over 2,500 free public libraries across the world, simply to “do good”. He said:

‘It was from my own early experience that I decided there was no use to which money could be applied so productive of good to boys and girls who have good within them and ability and ambition to develop it, as the founding of a public library.’

No one ever, ever, founded a public library because they wanted to do bad, or do bad things, or bring the worst out in people.

Every single step of human progress, from the swamp to the skyscraper, has been made possible through our ability not just to acquire knowledge, but to store, share and learn from it. Every time we put barriers in the path of that ability, we take a step backwards.

Helping children in a complex world

The famous burning of the Library of Alexandria in ancient times has become so apocryphal, it is hard to know what parts – if any – of the story are true. However, there is an undeniable truth in the warning of the story.

Today, our libraries may not be burning, but they are on fire.

Thankfully, we no longer depend upon clay tablets and scrolls to contain the sum of humankind’s knowledge, which could be destroyed by a single spark. But we face a greater, in many ways, more complicated challenge.

Our ability to access all the world’s information, every last byte of it stored for eternity, is expanding at an unprecedented rate. Unfortunately, at the same time, so is the ability to manipulate that information. This threat to civil society, democracy and informed debate means we must help equip our children with the skills to differentiate between truth and lies, in an ever-connected and increasingly complex world.

News story: fake news not fooling kids who read

Only libraries and qualified librarians can train children to do this. The organisation and classification of information is literally what they do. Which is why we don’t just need more public libraries, but a library and a librarian in every school. I see for myself the extraordinary diversity, engagement and pleasure in reading to be found in schools that have these.

How to make the most of your book nook or school library

Why librarians are magicians

My earliest memory of a library is not a grand old building or even a school, but a van painted a cheery bright yellow. A mobile library, that actually stopped outside our house in 1980s rural Northumberland. We didn’t pay for it. It just came. A van full of shelves of books. I sat on the grey plastic floor and flicked through stacks of picture books – mainly about dogs, burglars and zoos – for what felt like as long as I wanted.

To my young mind, the idea of a travelling library was as magical as the transformative powers of Mr Benn’s fitting room, or as spellbindingly mysterious as the fortune teller Professor Marvel’s caravan in The Wizard of Oz. Other vans came to the house, you see, to deliver parcels or furniture, or even fish. But I had no desire to climb into the back of those. I had discovered my portal to whole galaxies of new experiences.

You see, for me, libraries have always been magical, and librarians have always been magicians.

Last spring, I decided to revisit the book that was perhaps the first and most magical portal of all: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. It was the work that first opened my eyes to the human potential of storytelling. A wardrobe that let you into Narnia. Not that different to a yellow van that lets you into a hundred Narnias, I suppose.

My book, The Lost Magician, is in part an homage to that classic from a modern perspective. A story set in a library of the past, which might help the young readers of today prepare for the challenges of tomorrow. A story about a lost magician...

Now that might do some good.

Add a comment