'Friendship and glimmers of hope': How classrooms can be a place of healing for refugee children

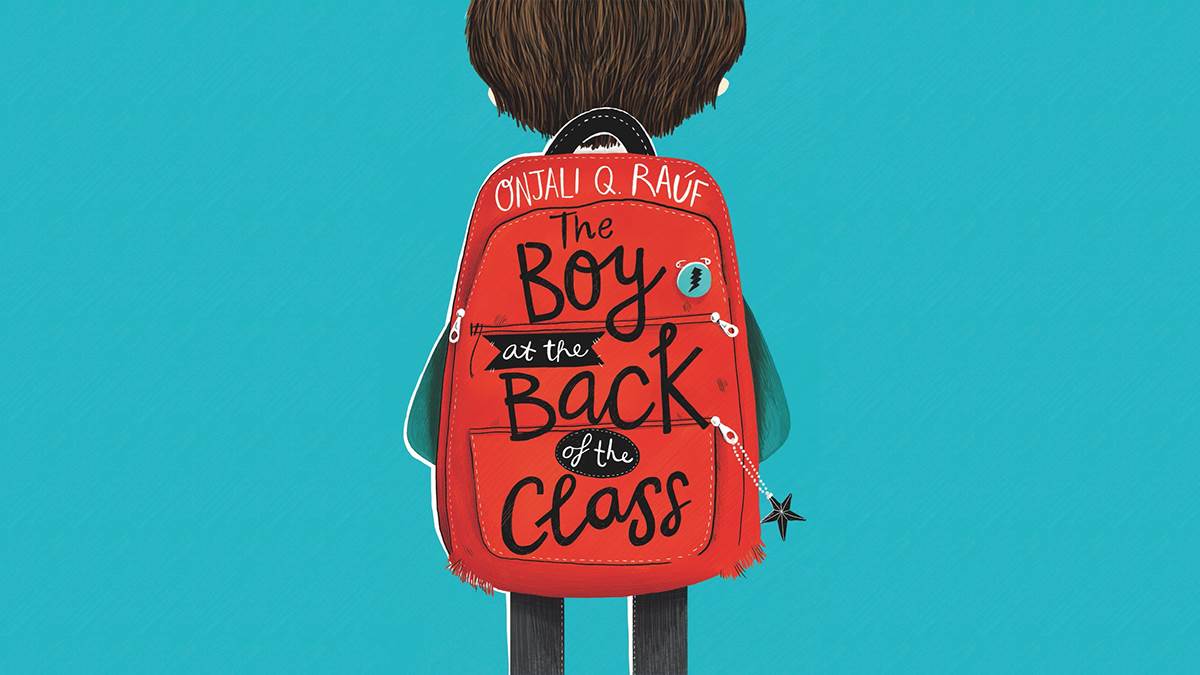

Published on: 20 September 2018 Author: Onjali Q Raúf

The Boy at the Back of the Class author Onjali Q Raúf knows that starting school can be a difficult time for young refugees - but also that the friendships they build can offer them hope.

When I was younger, in the final few weeks leading up to a brand new school term, I would get so excited that I could barely sleep - to the point where I would actually make myself ill.

A-million-and-one questions would flit through my brain like bees in a rush, and I would stay awake for hours, imagining the answers to each and every one.

They were questions like, will my new teachers be of the Miss Honey or the Miss Trunchbull variety? Will all my friends still be there, and what do I do if they're not? What will the popular kids think about my new school shoes? How can I get away with not wearing my glasses so that everyone will stop calling me 'Four-Eyes'? What new tricks will the school bullies be getting up to this year (and will I be safe)? Will the school library have the books I've been dying to read all summer but couldn't get my parents to buy? And most important of all, will the school canteen still be serving fish fingers and chips and sticky toffee pudding on Fridays (please God, let the answer be yes)?

But for a refugee child who is completely new to a country and plunged into living, breathing and functioning in cultures both alien and, at times, hostile to them, the 'normal' worries children have upon returning to school are superseded by genuine fears: fears which most of us would find hard to imagine.

And despite having had the honour of meeting hundreds of refugee children in my voluntary work as an aid worker and learning of their struggles - both before and after they reach the UK - I still cannot bring myself to confront just how deeply lonely they can feel. Especially for those who have survived the journey when their parents and other loved ones haven't.

School is a battleground - but there's also hope

For most refugee boys and girls like Ahmet, the young boy in my book, school is yet another battleground, and one to which they must quickly adjust in order to survive. From getting to grips with speaking, reading and writing in a brand new language at warp speed, to becoming acclimatised to a classroom setting where bombs and tear gas aren't a reality, the obstacles and traumas they face daily can seem insurmountable.

Yet alongside those struggles - colossal and unfathomable as they may seem to those of us who have not experienced war, starvation, homelessness, outright hostility and devastating racism - are endless moments and glimmers of hope. And the strongest of those glimmers always seems to be rooted in friendship.

The greatest moments of my work (and sometimes my life) in relation to the refugee crisis are seeing people young and old break through every kind of barrier imaginable to reach out to someone in need. And whilst it is beautiful when adults cross those divides, there is something especially magnificent when children make the effort.

They seem to do it with an innocent steadfastness and in a spirit of self-sacrifice that is often all-encompassing. I love seeing and hearing of instances when a refugee child in a deep state of trauma is befriended by someone of whom they are initially deeply suspicious, and noting how their faces, their demeanour, and their eyes literally light up when they finally realise they have a friend standing before them.

How real life inspired The Boy at the Back of the Class

There are many instances taken from real life of children going out of their way to befriend 'the strange/silent/new' kid in The Boy at the Back of the Class.

An example is the story of the lemon sherbets which the narrator tries to give to Ahmet on his first day: this was inspired by the story of a young refugee girl living in the camps of Calais, who was given endless packets of crisps by another young French girl living in the local area - whose parents dropped off fresh bread whenever they could - in her attempt to make friends.

I heard of her efforts through a fellow aid worker, and thought how beautiful it was that this little human being was trying to communicate her desire to be a friend through a packet of crisps.

The Boy at the Back of the Class was never really written with the sole aim of highlighting the struggles refugee children face when entering a new school. The main hope was that it would serve as a reminder - perhaps more to myself than anybody else - of the huge roles our children play in filling the immense voids created by The Grown-Ups of our world, and of just how much we have to learn from them.

The classroom will always be a battleground for every child, regardless of who they are, how old they are, where they have come from and how big or small those battles may be.

But for a refugee child especially, it can also be a place of immense healing and hope and recovery. If, that is, we're all willing to help make it so.

Read our review of The Boy at the Back of the Class

More books about refugees and asylum seekers

Add a comment