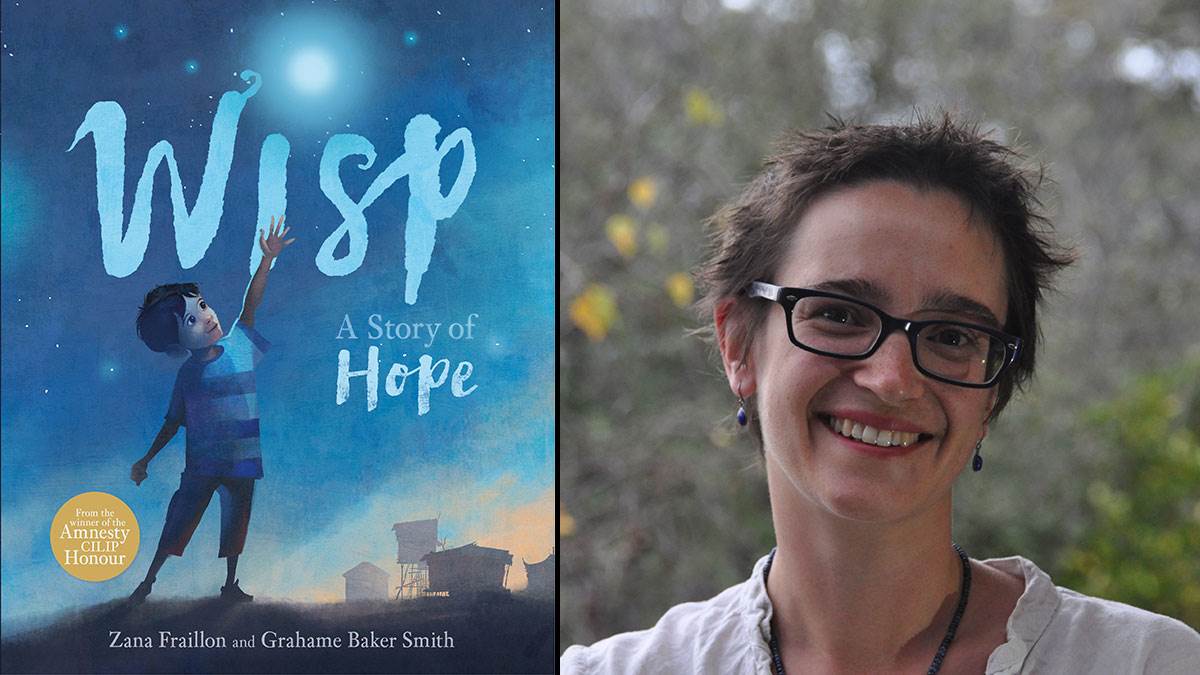

'A story of hope': Zana Fraillon on how she wrote a picture book about refugees

Published on: 16 October 2018 Author: Zana Fraillon

When The Bone Sparrow author Zana Fraillon was asked to write a picture book about refugees, she had no idea how to start. But then the idea of Wisp came to her...

It was my publishers at Hachette who asked me to write a picture book about a child growing up in a refugee camp. At first, I wasn't sure I could do it. I stood at the kitchen table, unable to fathom how I would undertake this challenge. But I knew I desperately wanted to.

I wanted to for the same reason I wrote The Bone Sparrow and The Ones That Disappeared. I wanted to give voice to those who had been silenced, so we know to listen for the real voices, and the real stories of the real people, who for too long have been silenced. Hidden out of sight. Twisted into nothing more than statistics to be batted about and used for political gain.

And I also knew that young children, with their wonderfully wide open minds and ability to imagine worlds we adults can't even try to conceive, are the perfect readers.

They gladly jump inside another's skin and parade about, exploring lives and existences so different from their own with infectious enthusiasm and wonder.

They unhesitantly demand answers to all the unasked questions, poking and prodding at all the details hidden in the shadows until their curiosity is sated - for the time being. This was exactly the audience I wanted to reach.

But how could I show these brilliantly, enthusiastic young people the reality of life in a refugee camp without destroying their very belief in the world? And how could I pay respect to the millions of real life victims and survivors without showing the horrific conditions they are living in? How could I help bring their voices to our ears and at least try to create some sort of bridge between our two worlds?

How Wisp came alive

I can't quite remember how the idea of a wisp came to me. I know I had been down at the river with my own children, climbing trees, blowing on dandelion seeds and making wishes. I know I had done more kitchen table gazing, to no avail.

I know I had been thinking about the vastness of the world, and the smallness of the camps and detention centres. I know I went to sleep, with pictures drawn by refugee children of their childhoods behind the wire fences floating through my head, and had wondered what one would make of a river, when seen for the very first time, or a tree, if it was first climbed when you were no longer a little child with a light body and agile limbs to swing and jump with such carefree joy.

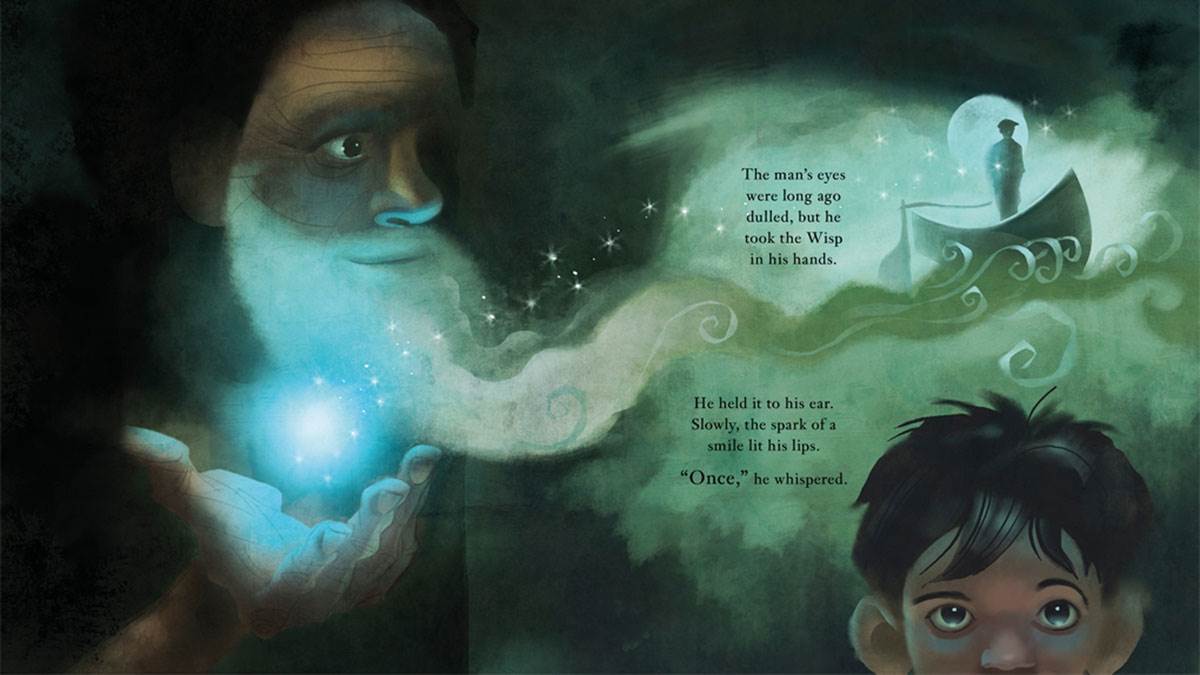

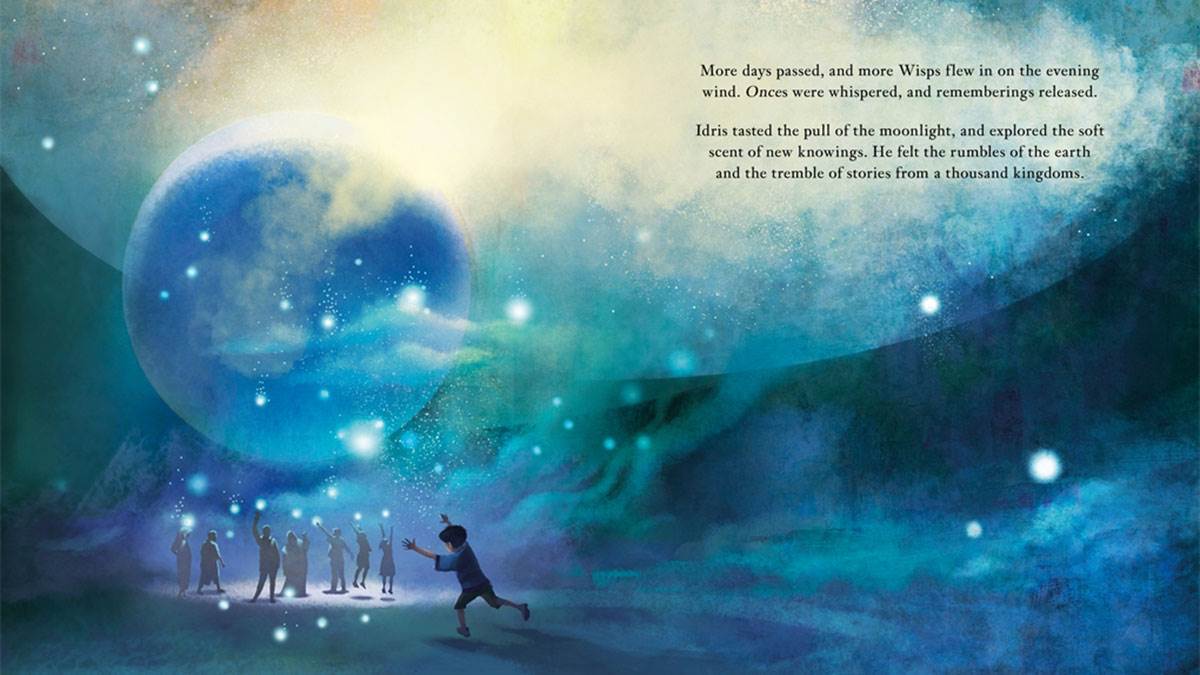

And when I woke, Wisp woke with me. Just like I wrote in my first draft, a wisp was born. I knew exactly what the wisp would do – it would show the brilliance and wonder and knowledge and understanding of the people forgotten in refugee camps and detention centres worldwide. The songs and the stories and the cultures and the dreams that we are all missing out on.

And I knew that it would be a child that would find the wisp, when all others had failed to see its beauty and promise. Because as adults, we so often fail to see beauty and promise.

I also saw how I could make this story one of hope, even when the setting was so inherently bleak. All I had to do, all the wisp had to do, was to give the readers a chance to imagine a different reality.

Bringing the story to life

When Hachette came back with Grahame Baker-Smith as an illustrator, I knew immediately that he would be able to transform my words into a world more brilliant than I could even imagine. He did, and in a way that so perfectly matched my own ideas and thoughts that it felt as though the words and pictures had always co-existed.

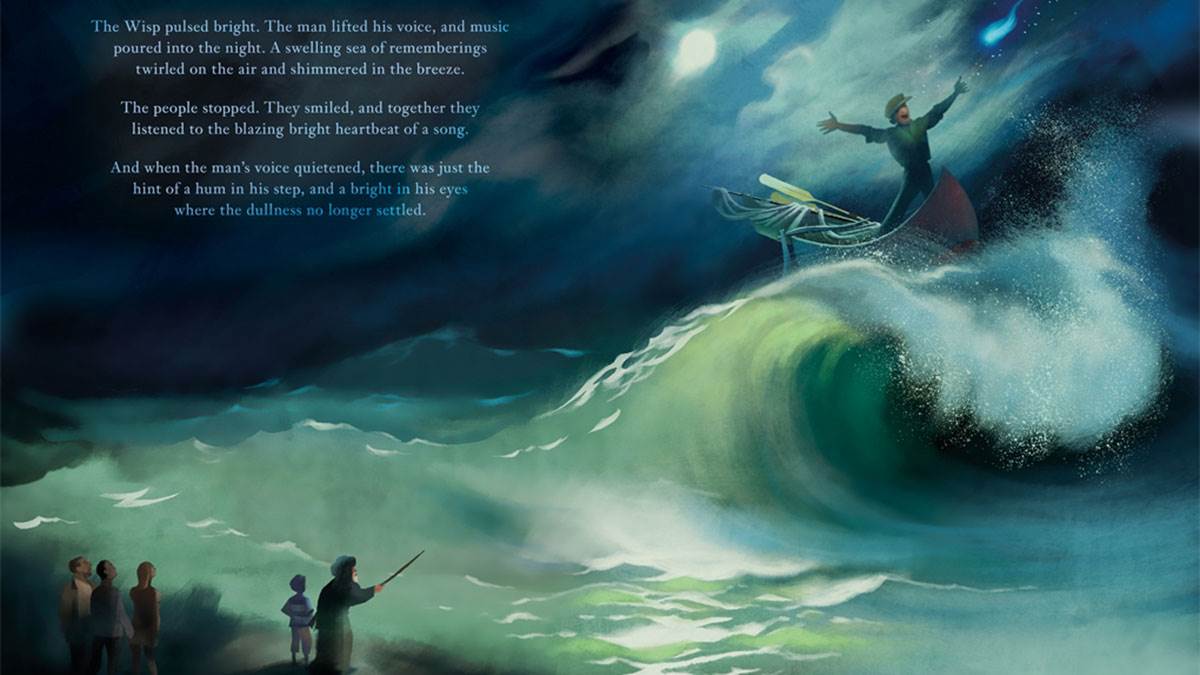

Grahame brought the story to life. He gave the people bodies and memories and dreams and desires. His pictures allow the reader to see more with each reading, to imagine more, and to somehow see beyond what is shown on the page.

Wisp became more than a story of a child growing up in a refugee camp. It became a springboard for understanding how our world is now, and hope for everything it could become.

It is about imagining our past, our stories, our futures. About imagining the world we want to live in. It whispers of community, and of story, of memory and shared culture, of difference and of celebration.

And I realised that creating a picture book for young people about the refugee crisis is perfect, because it is these young people, from both worlds, that will cross that bridge together. There is always hope for the future, as long as we can keep imagining.

The Day War Came: telling the story of child refugees

How classrooms can be a place of healing for refugee children

Boy 87 author Ele Fountain: 'I truly understood the need to write'

Topics: Picture book, Politics/human rights, Refugees/asylum, Features

Add a comment