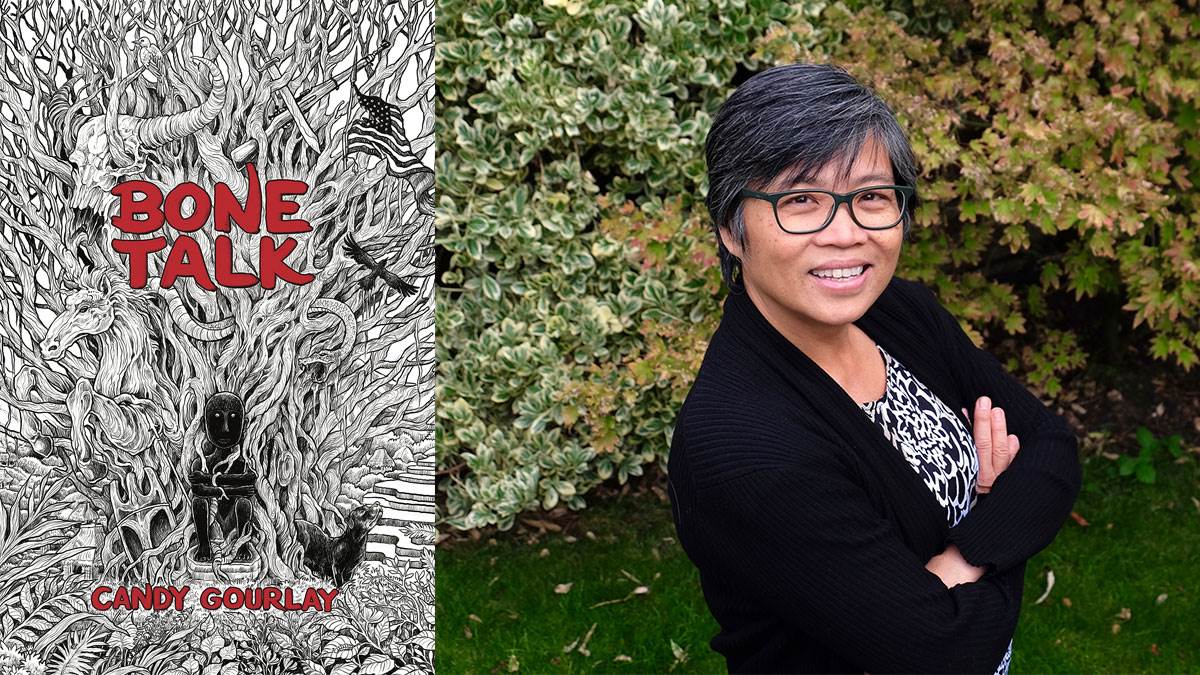

Another story to tell: writing about cultural appropriation in Candy Gourlay's Bone Talk

Published on: 17 October 2018 Author: Candy Gourlay

When author Candy Gourlay set out to write about the appalling "human zoos" of the past, she didn't know that her book would swerve in a different direction – and ultimately, for the better.

My third novel, Bone Talk, was published in August. But truthfully, it was not the book I set out to write.

I had begun to write the story of a boy who finds himself in the St Louis World Fair of 1904. A world fair is a huge exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of a nation – and the one in St. Louis was epic! It exhibited amazing new technology like the x-ray machine, the electric typewriter, the baby incubator, the first electric wall socket, and a gazillion other new inventions!

Most of the United States was still rural and electricity-less and more than 19 million Americans came to gape at these wonders.

But my hero was not going to be one of those 19 million. He was one of the exhibits.

Watch Candy Gourlay talk more about the St Louis Fair

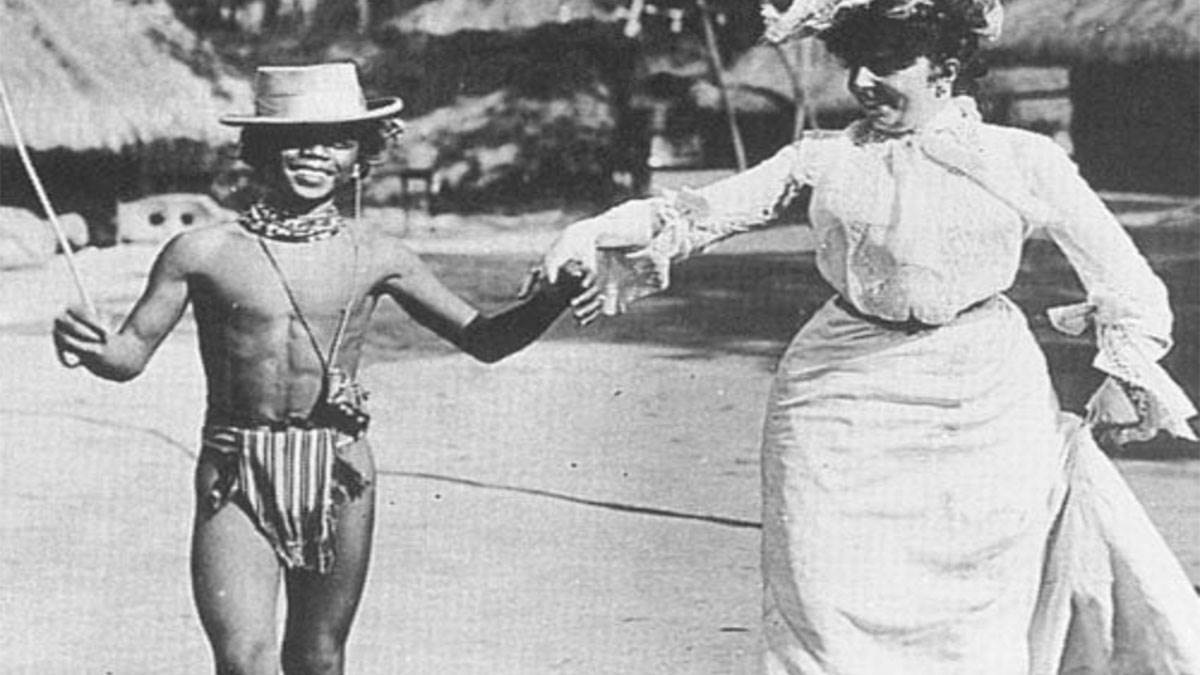

From human exhibit to hero

Back in the 1800s and the early 1900s, European countries, and later, the United States, saw nothing wrong with human zoos. Travel was beyond the reach of many and displaying people from other countries was considered educational. Perhaps it was. But the people who came to look were encouraged to feel superior to the people on show. And the people on show – well, you can imagine how they must have felt.

The St Louis Fair exhibited people from many different cultures: the Ainu, an indigenous people of Japan; African tribesmen; Native Americans; Patagonians …

But the World Fair’s star turn was an exhibition of selected peoples from the Philippines.

My hero was going to be a boy who belonged to a mountain people called ‘Igorots’, who at the time were headhunters.

How to write this story well

I was so excited to write the book. I wanted to turn the tables on all those people who came to stare. I wanted to show how America must have looked to my Igorot hero.

But slowly I realised that to begin my story at the World Fair, to show the G-string wearing Igorots against the backdrop of the Fair’s colonnaded buildings and grand inventions, would be a repeat of the indignity they suffered in 1904 – when they were presented to the world as savages. To this day, the Igorots continue to suffer the backlash from that fair, forever embedded in the American memory as a lurid sideshow, and in the Philippines, enduring discrimination and treated as inferiors by some Filipinos.

A book without context would be horribly harmful – and the worst kind of cultural appropriation.

I asked myself: “Am I the right person to tell this story?”

The answer was: MAYBE … if – and it was a big IF – I could write the story well.

But how do I write the story well?

I thought long and hard about it. Was it about just getting all my facts right?

History written by one side

I spent many hours in the British Library reading many books and soon realised that the written record was not told by Igorots but by American diarists, ethnologists, politicians and historians.

The world has largely forgotten that the Philippines was invaded by the United States in 1899. Filipinos resisted in a war that came to be called the Philippine Insurgency by Americans and the Philippine American War by Filipinos.

The American histories and diaries from that long-ago era were written with many agendas. One of the agendas was to portray the Igorots as primitives and savages with silly superstitious beliefs.

The Igorots were secretive about many of their practices, including headhunting, but Americans were eager for sensational images to send home. One photographer got Igorots to pose with artificial heads and then toured America exhibiting his photographs and proclaiming the savagery of Igorots. Fake news – but America loved it.

This meant the story of the Igorots was told by their enemy. It became even more important to get their voices right.

I found a diary written by an American housewife, Maude Jenks, who accompanied her anthropologist husband, Albert, during his time in the Philippine mountains. Albert wrote a detailed, anthropological text called The Bontoc Igorot about the culture they encountered. Maude wrote about the people who liked to hang around her front porch, the little boys who borrowed early readers and tried to teach themselves English, the women who haggled over vegetables at the market. Here at last was a record of ordinary Igorot voices.

Seeing the world with Igorot eyes

I guess, for the author grappling with the issues of cultural appropriation, the most important thing is not just to represent facts but humanity. We’ve got to get the soul right.

I need my reader to see the world from the eyes of the Igorot. And in so doing, experience their world of belief and ritual not as a curiosity … but as logical and true.

So in the end, the book I wrote – Bone Talk – is not set in the World Fair. It is set much earlier, in 1899, when the invasion forces of the United States enter the remote mountain region of the Igorots.

Samkad is ten years old, old enough to become a man. He can’t wait to be given his own shield, his own spear and his own axe to chop off the heads of his enemies. His best friend, Little Luki, watches enviously. She wants to become a warrior too, but no girl in their world has ever become a warrior.

Suddenly, strangers come to the village. First, a boy named Kinyo whose magical throat can speak the strange noises of other languages. Then, a kind, bumbling giant named Mister William, who is covered all over with hair the colour of dog. And then men who look like Mister William and yet are cruel and murderous, soldiers of the American invasion that led to the Philippines becoming a US colony for the next 50 years.

In their home, on their terms

'None of it happened but it’s all true,' says the screenwriter Aaron Sorkin, about his films featuring the inventor of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg, and the Apple magnate, Steve Jobs.

I can say the same thing about Bone Talk. I have written fictional characters and put them in a fictional village … but the essence of their experience is absolutely true. This is what it’s like to meet your invader for the first time before he changes you forever.

Frank Cottrell Boyce, author of the brilliant and funny Millions, recently told an audience of authors and librarians: 'Books are overwhelmingly important compared to other media because only books can show us that nothing is as simple as we think. It’s complicated.'

I am still hoping to write a book set in the St Louis World Fair. But before they discover St Louis, I need my readers to visit a world of mountains carved into rice paddies and mossy, misty forests. A world where the invisible spirits of the dead live alongside the living. A world where nothing has changed since people began to remember.

I need my readers to meet the Igorots in their own home, on their own terms.

Topics: Historical, Inclusive, Politics/human rights, Writing, Diversity (BAME), Features

Add a comment