How historical fiction speaks to young people

Published on: 25 January 2024

Author Candy Gourlay shares her thoughts on the value of historical stories, and recommends her favourites.

I love history. Correction: I love history now – because when I was a child, history meant dates to memorize, figures from long ago that I couldn’t relate to and events that seemed to have no relevance to my own life.

It was only in adulthood that I fell in love with historical fiction, when I read Toni Morrison’s Beloved just because it was a set text in my son’s English class. Beloved is set in a historical moment that scholarly texts describe as ‘liminal’ – a moment on a threshold, like when a door opens and you enter a completely different space. In Beloved, this was the end of slavery and the beginning of so called ‘freedom’ for Black Americans in the 19th century. (To be honest, the book did not speak to my teenage son … but it spoke to me. I continue to reread it to this day.)

Liminal spaces …standing on the boundary of what had been, looking into the uncertain future is something we will experience over and over in our lifetimes.

I believe readers learn a lot from living these charged moments vicariously in good fiction. These liminal spaces can be frightening and dark, but experiencing them through stories from the past we learn that life goes on, life gets better. We learn that there is hope.

I’ve noticed that the best historical fiction seems to favour liminal spaces.

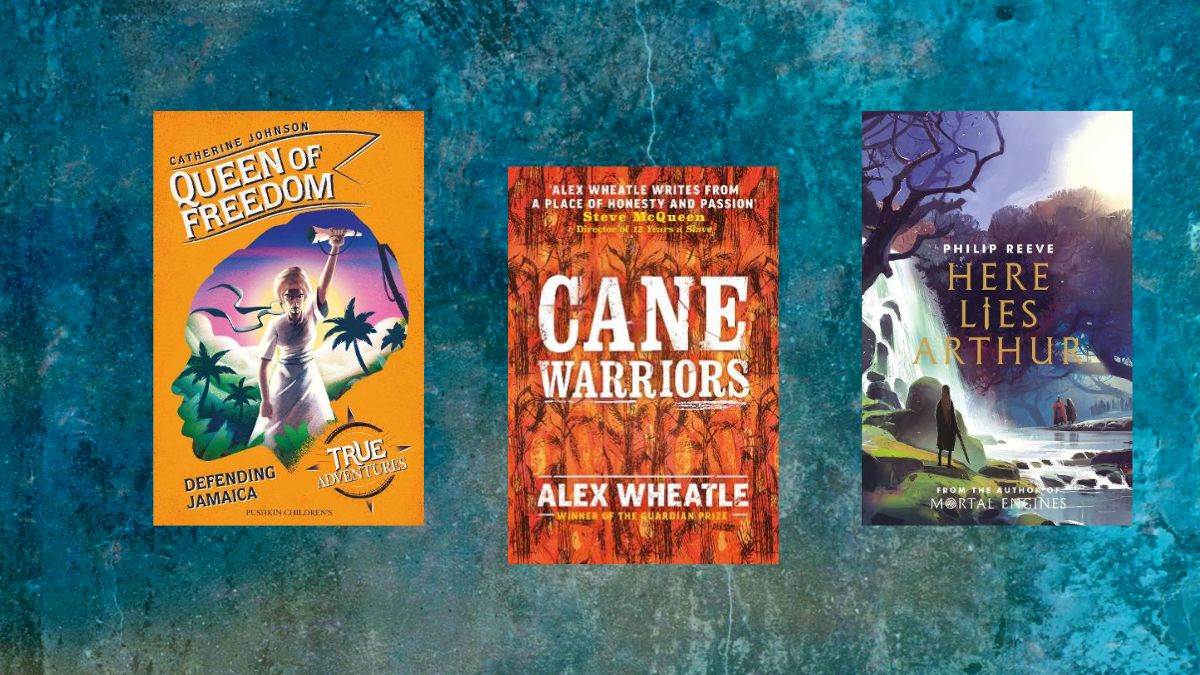

Here Lies Arthur by Philip Reeve (11+), set in the 5th century with crumbling remains of Roman temples and brute warlords fighting to set up their own fiefdoms, tells the story of how Arthur became king via the machinations of Merlin, more an Alastair Campbell-style strategist than a wizard. A powerful book.

Revolution is a liminal space, a moment when despair turns into action. Cane Warriors by Alex Wheatle (13+) and Queen of Freedom by Catherine Johnson (9+), are both set in Jamaica when enslaved peoples turn against their brutal British overlords. A boy decides to become a Cane Warrior and join the resistance. A woman leads escaped slaves and becomes a guerrilla leader. Brave and heart-stopping.

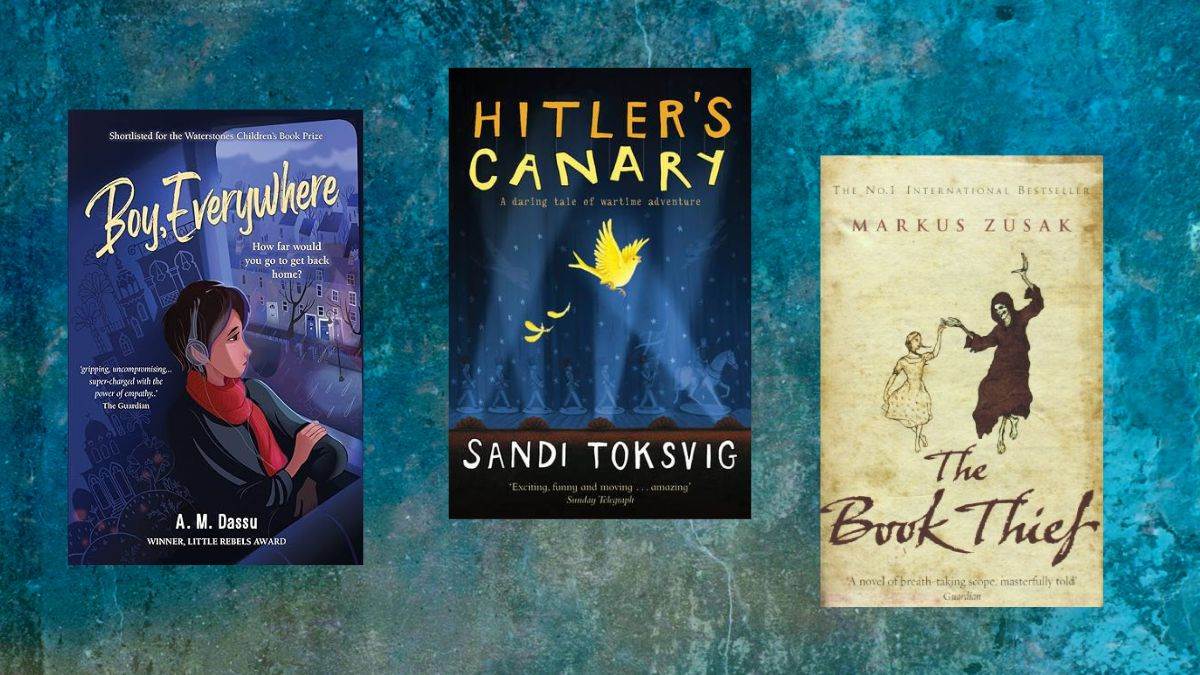

War is another liminal space and I’ve noticed that World War II is a popular setting for children’s historical fiction. I love the ones set in unexpected places – like the big hearted and comedic Hitler’s Canary by Sandi Toksvig (9+) set in Denmark as the Nazis march in. And the ones with unexpected heroes like the working class kids who hide a German pilot in The Machine Gunners by Robert Westall, or the absolutely ordinary middle class kid turned refugee in Boy Everywhere by A.M. Dassu, the Germans who risked their lives to save Jewish children in the moving The Safest Lie by Angela Cerrito, Death snarkily narrating the story of The Book Thief by Markus Zusak, the Sikh pilot in the French countryside in Mohinder’s War by Bali Rai.

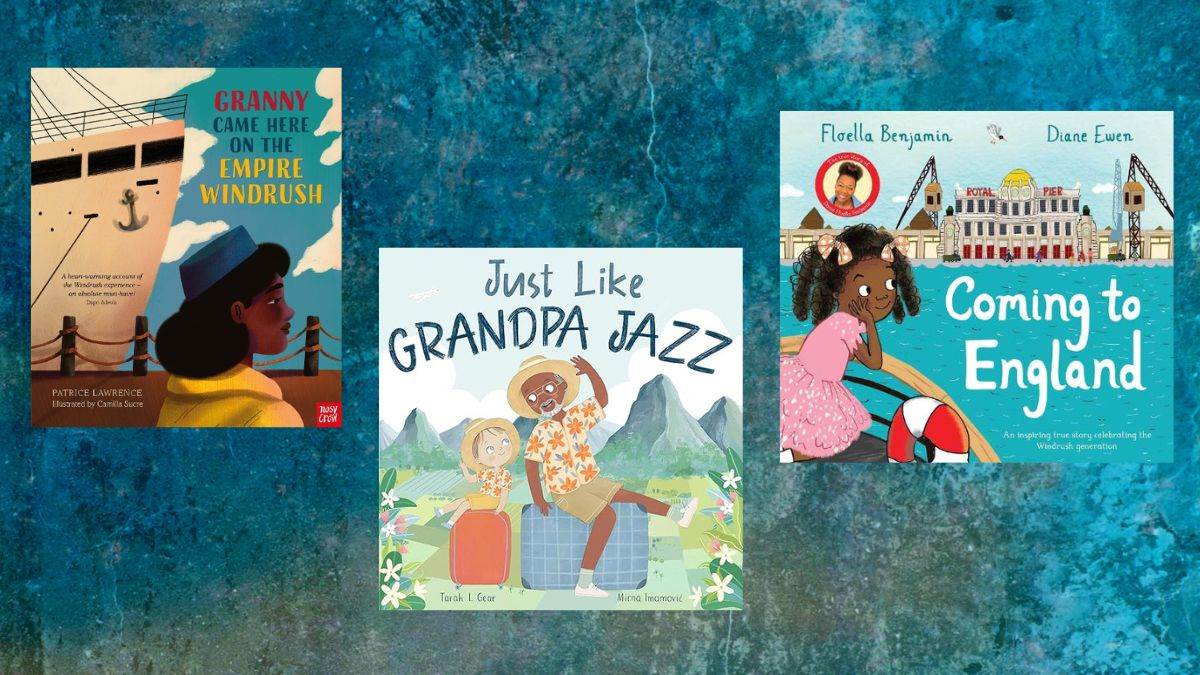

Leaving and arriving is another liminal space and I have been so heartened to see the flood of books celebrating the iconic Empire Windrush, one of the ships that ferried Caribbean peoples to fill labour shortages in mid-20th century Britain. Among them are Just Like Grandpa Jazz by Tarah L Gear, illustrated by Mirna Imamović, Coming to England by Floella Benjamin, illustrated by Diane Ewen, and Granny Came Here on the Empire Windrush by Patrice Lawrence, illustrated by Camilla Sucre.

I am from the Philippines and the canon of historical fiction for young readers set in my native land is very small. It has really pleased me to have now written three books set in foundational histories of my country – and yes, all of my books occupy those fascinating, liminal spaces!

There’s Ferdinand Magellan, one of the First Names series combining comics and biography, hilariously and skilfully illustrated by Tom Knight. Every Filipino child is taught that it was the Portuguese (turned Spanish) explorer Ferdinand Magellan who ‘discovered’ the Philippines. But how do you discover people who are not lost? Ferdinand's little adventure was the beginning of profound change in the fortunes of Filipinos.

It really pleased me that my publisher included a cartoon of early Filipinos on the cover saying, ‘Oy! We’ve lived here for centuries!’ The whole book explores (with humour) that liminal period of 16th century European explorers discovering the East, and what followed.

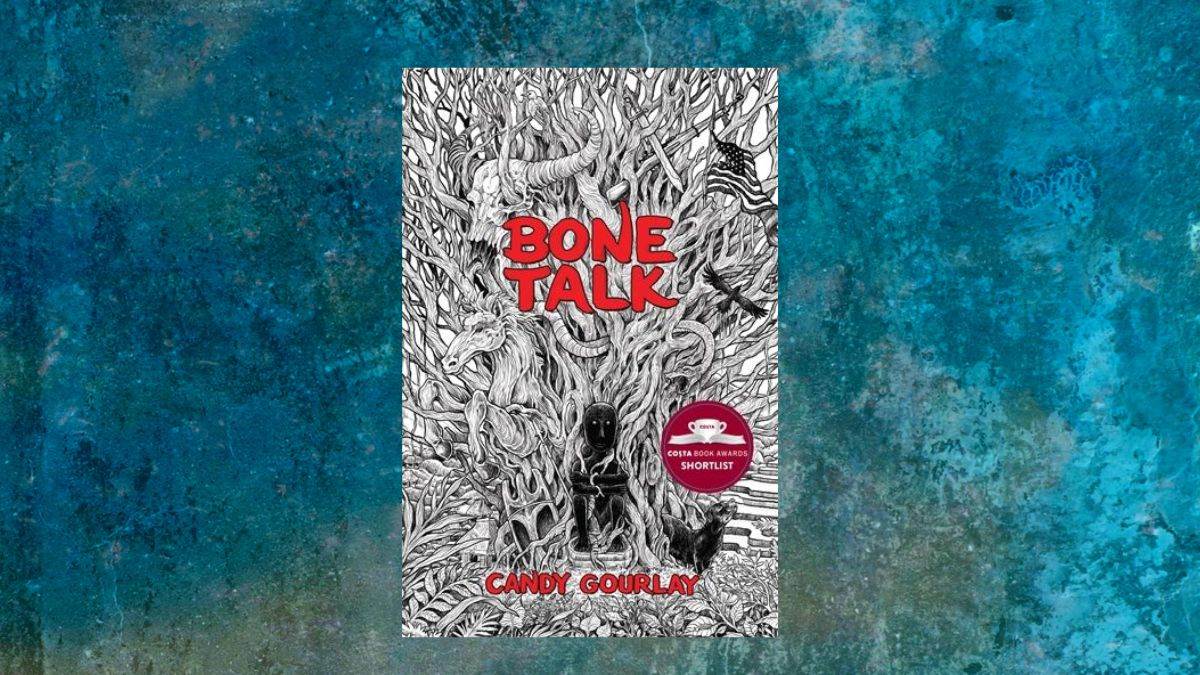

Bone Talk (10+) is set in the Philippines of 1899 – Samkad knows what he wants to be when he grows up: a warrior like his dad, with his own spear and shield. But then strange-looking men with eyes the colour of the sky and hair the colour of straw arrive, and everything changes with the United States’ invasion of the Philippines. Bone Talk was shortlisted for the CILIP Carnegie Medal and the Costa Prize in 2019.

This was followed by Wild Song – which has just been released in paperback – woo hoo! – peopled by the same characters as in Bone Talk but not a sequel. It is set in 1904, and members of Samkad's village are transported by Americans, now governing the Philippines, to the 1904 World's Fair in St Louis, Missouri.

Wild Song (12+) is told in the voice of Samkad's best friend, Luki (who, now that they're teenagers, has become his love interest). It's not just a run-of-the-mill first-person narration either; Luki is recounting events to her just-dead mother. Stories of the World's Fair of 1904 have previously been told by Western voices. By having Luki speak to her mother I could evoke an indigenous voice from an animistic background.

What happens to Luki's people at the World's Fair makes for shocking reading but I wouldn't have written Wild Song if I didn't have confidence that my young readers will relate to Luki's trials and tribulations.

They will quickly recognise unsavoury vintage attitudes that persist to this day. They will themselves have experienced the confusion of sorting right from wrong when powerful voices are shouting in your ears. They will themselves be resisting the expectations of their elders, without being able to articulate what they really want.

And recognising themselves in this true story from a hundred and twenty years ago, they will realise that they, like Luki, have the resilience to face overwhelming odds and move through their own liminal moments with grace and hope.

Wild Song has been nominated for the Yoto Carnegie Medal for Writing and shortlisted for the inaugural Nero Book Award.

Topics: Historical, Features