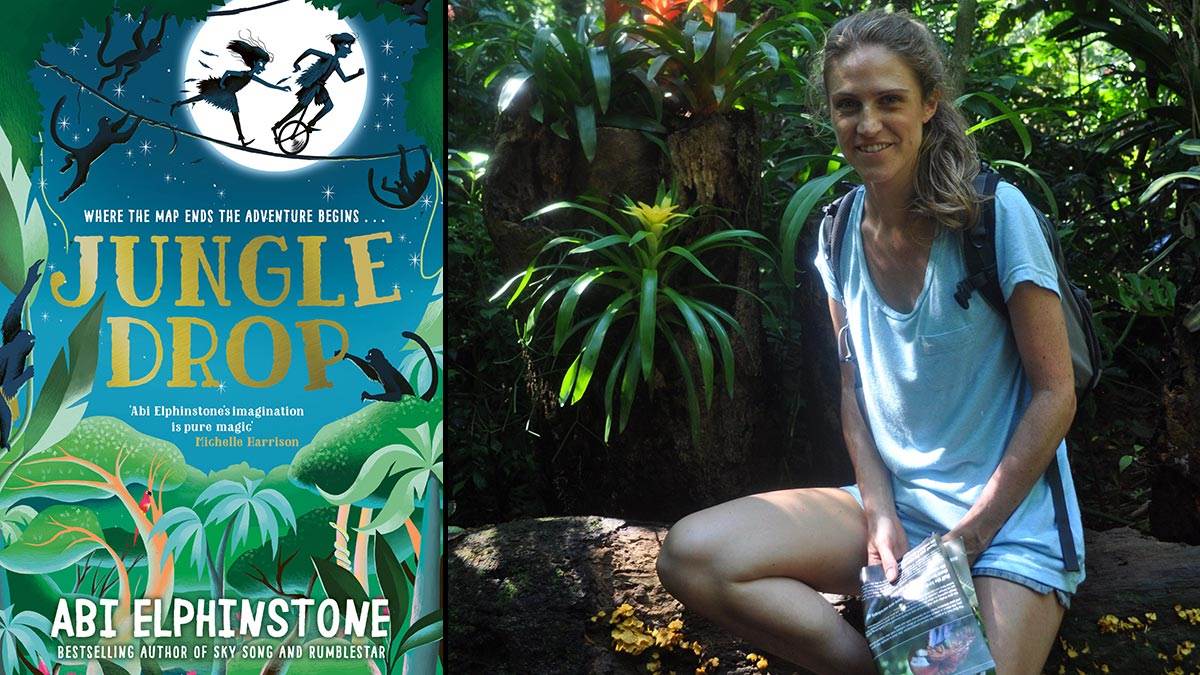

'Kindness is what holds worlds together': How Abi Elphinstone's jungle adventures inspired her new book

Published on: 01 October 2020 Author: Abi Elphinstone

When author Abi Elphinstone visited South America, she formed a strong connection with nature that inspired her new book! She tells us why children need those links with the natural world...

A few years ago, I visited the world's largest tropical wetland. The Pantanal is an enormous patchwork of lagoons, marshes and lakes sprawling Brazil, Bolivia and Paraguay, and it's home to 4,700 plant and animal species - making it one of the most biologically diverse environments on Earth.

I snorkelled in the crystalline waters of the Olho D'água river on the fringes of the Pantanal amongst anacondas (the heaviest snake in the world, with some weighing in at a colossal 200kg), piranhas and pacu. As if the first two species don't sound ominous enough, pacu can reach up to 25kg in weight and have alarmingly human-looking teeth!

Despite feeling unnerved by the presence of these creatures, it was impossible not to marvel at the beauty of the aquatic world around me. Unlike many rainforest rivers, which are murky in colour, the Olho D'água river runs absolutely clear because it passes through a limestone karst nearby and the minerals purify the water.

The river is therefore a light-filled temple of wonder, just one mile long but home to over 65 varieties of fish, as well as alligators and giant otters. And a single snapshot shows its perfectly balanced ecosystem: under a fig tree, tamarins feed on fruit, every now and again dropping some into the river which, in turn, feed the piraputanga fish, who provide food for the dorados, the 'kings of the river'.

I watched capybaras, agoutis, tapirs and giant anteaters scavenging for food while tarantulas the size of side plates rested on leaves and hyacinth macaws, parakeets and Toco toucans - the largest of all toucan species, with beaks that measure up to 50% of their surface area - chattered from the trees.

There seemed to be so many different species in the Pantanal that it felt like you could go for hours without seeing the same type of animal or plant twice. All of them seemed to be flirting, governed as they are by the urge to reproduce and pass on their genes. Trees must scatter their seeds, flowers must be pollinated and animals must display elaborate courtship rituals.

Everything felt interconnected in the Pantanal.

Even the smallest of creatures, like the tiny apple snail, seemed to have a part to play in keeping life there going. The wetlands flood once a year, causing plant-life to die and decay. When this happens, decomposing microbes empty the water of oxygen which suffocates larger decomposers, but the apple snails have both gills and lungs so they thrive in anoxic waters and recycle the nutrients there, turning them into nutritious fertilizer for plants to grow once again.

This sense of interconnectedness in the wild was something I wanted to convey in my latest book, Jungledrop. With the increase of mobile phones and video games, many children are feeling isolated at a time in their lives when they are on the brink of questioning the world around them and their place in it. But they need only look to nature to learn that the oxygen we breathe is generated from the trees and marine plants around us, meaning we all belong to a vast and beautiful web of life.

How my adventures inspired Jungledrop

The Pantanal was a tapestry of noise - barks, coos, grunts, clicks, shrieks - but just south of there, near Bonito, I made an altogether quieter discovery: Abismo Anhumas, an enormous, ancient cave that drops 72 metres into the ground before culminating in an underground lake.

I abseiled the 72 metres down into the cave, which was studded with gigantic stalactites and lit only by a single shard of sunlight that reached down from the jungle above. I felt like Jill Pole descending into the Underland in C.S. Lewis' The Silver Chair!

When I reached the bottom of the cave, I donned a full body wetsuit and swam in the freezing water over dozens of giant stalagmites rearing up from the depths of the lake. The experience was so completely otherworldly - and the 72 metre rope-climb out again so completely exhausting - that I have felt compelled to include mysterious caves in many of my books since. In fact, in Jungledrop the heroine, Fox Petty-Squabble, stumbles across a deeply magical cavern named Cragheart.

The tropical world of the Pantanal and its surrounding areas built my fictional world in Jungledrop. Its pink trumpet trees became my glow-in-the-dark gobblequick trees. Its marsh deer became my swiftwings (a little bit like hippogriffs, but clumsier). Its jaguars became my golden panthers. Its lianas became my Hustleway, the network of jungle creepers that characters race over on enchanted unicycles).

But with Jungledrop, I wanted to write a story that not only revelled in the beauty of the jungle but also highlighted its fragility.

Due to infrastructure development, untreated waste pollution and deforestation, the Pantanal's native vegetation - which provides water and food for millions of people in the region - could disappear by 2050. And so in Jungledrop, I have a rainforest on the brink of ruin. Gobblequick trees are dying, thunderberry bushes are withering away and magical creatures are struggling to survive.

Children need to be aware of the severity of the threats facing our rainforests, and the potential consequences for us all, but they also need to feel that they can do something about it. Fear paralyses but hope galvanises.

And so, on the surface of things, Jungledrop is an adventure story about 11-year-old twins, Fox and Fibber, who are whisked off to the Unmapped Kingdom of Jungledrop to find the long-lost Forever Fern which has the power to restore rain to our world and save the glow-in-the-dark rainforest of Jungledrop.

But really, this is a story about a young girl finding her way - with the help of a flickertug map - and learning what most grown-ups take a lifetime to understand: that kindness - to others, to our planet and, perhaps hardest of all, to ourselves - is what holds kingdoms and worlds together.

Topics: Adventure, Animals, Environment, Nature, Features

Add a comment