'Children see themselves in Kipper': Mick Inkpen on 30 years of The Blue Balloon

Published on: 14 March 2019

It's 30 years since we were introduced to children's book favourite Kipper in The Blue Balloon! We spoke to author-illustrator Mick Inkpen about why the dog is still so popular with young readers...

It's amazing that The Blue Balloon is 30 years old! Congratulations. What first inspired the story?

Three ideas merged in the course of one afternoon. Sadly it doesn't always work that way!

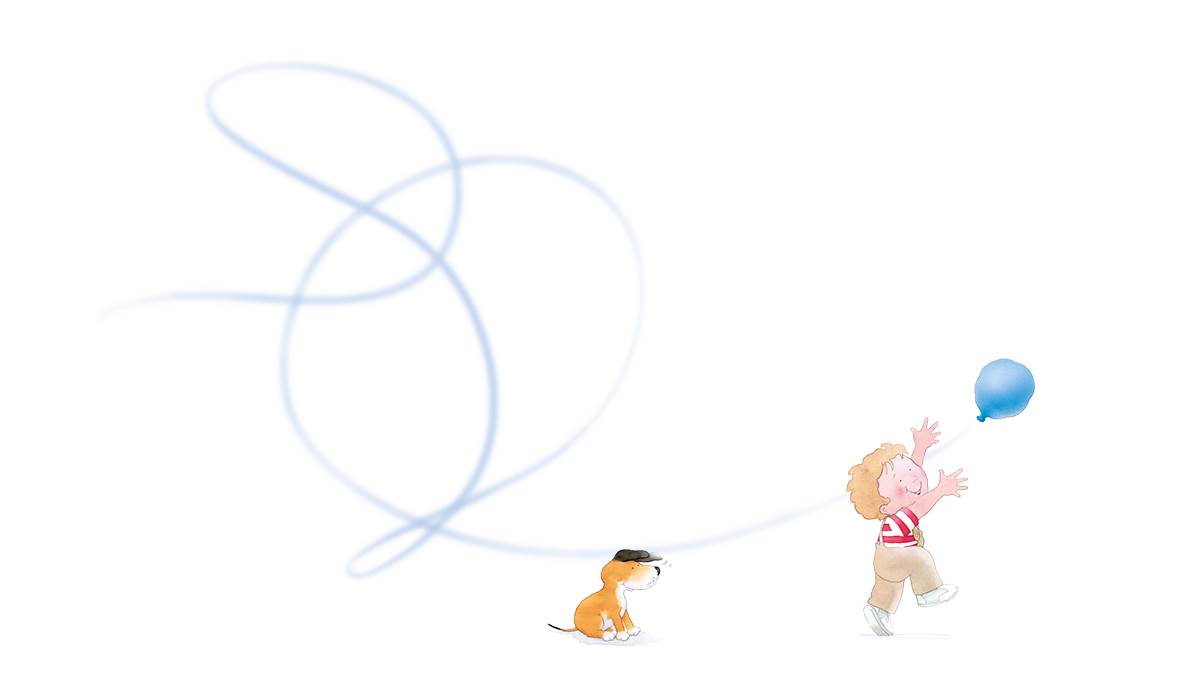

Firstly, I wanted a subject with universal appeal and a simple balloon seemed perfect. Balloons are essentially happy, celebratory things. They cost very little yet they possess personality; they are by turn floaty, farty, bouncy and explody. And like us, they grow wrinkly and expire.

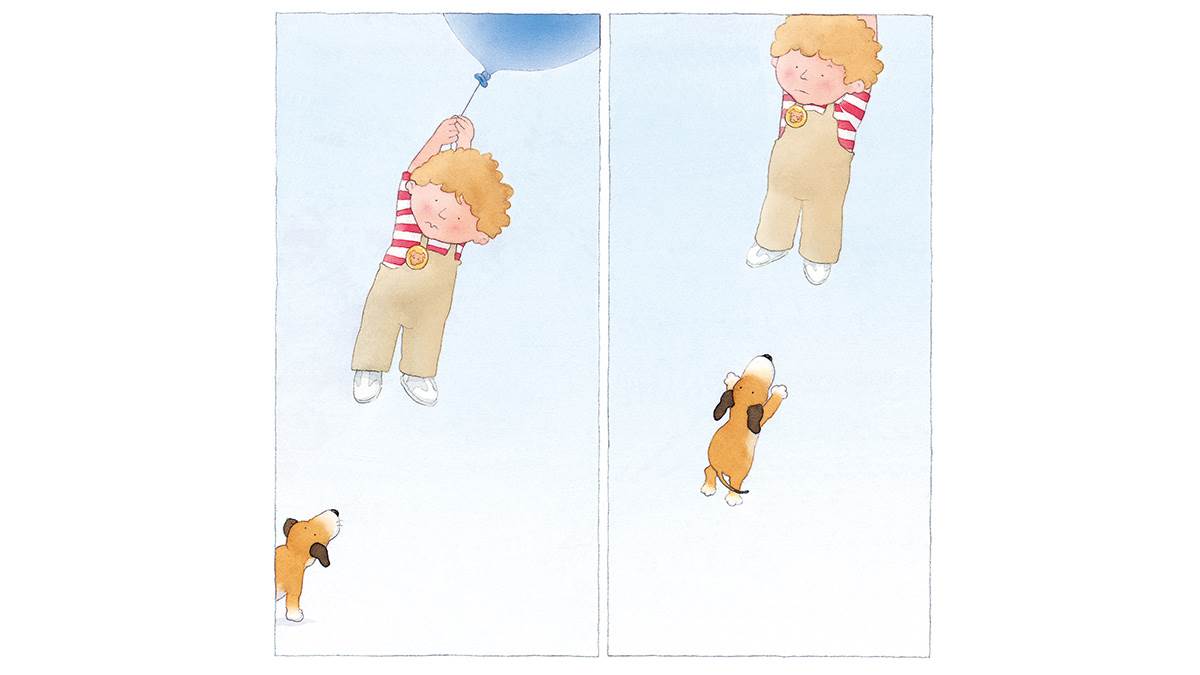

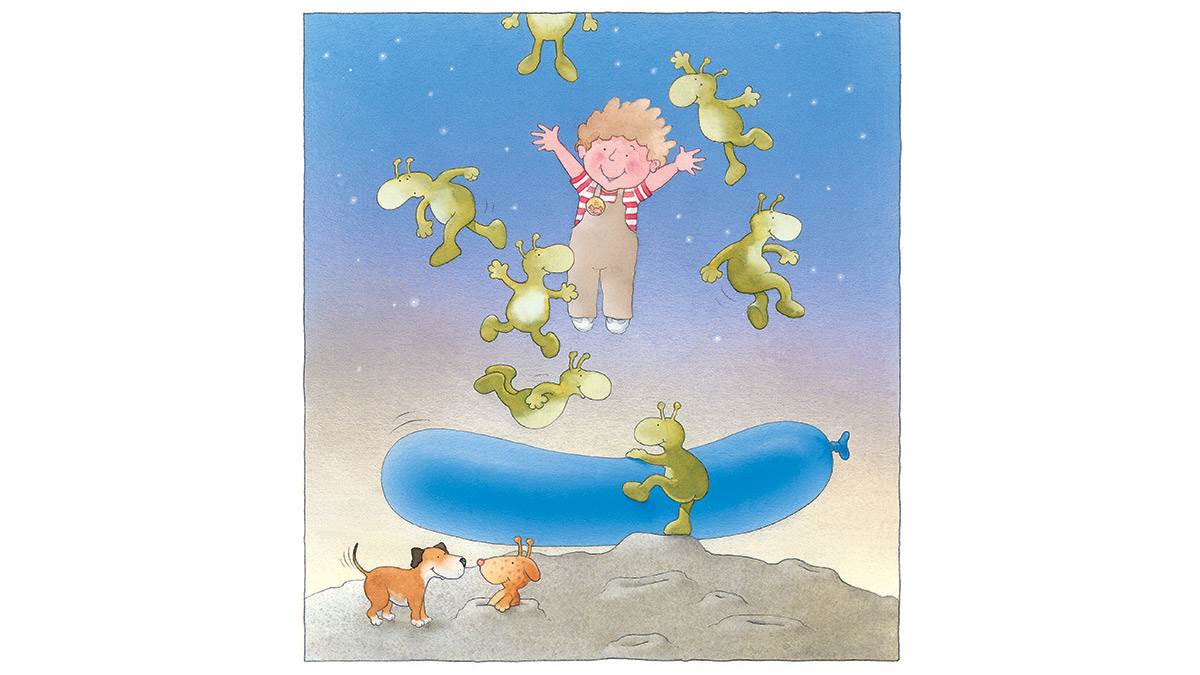

Secondly, it occurred to me that there was no reason that my balloon should not possess 'Strange and Wonderful Powers'.

Thirdly, I began to wonder if it might be possible for the balloon to escape the boundaries of the book itself. At this point, the oversized pages and fold-outs began to feed back into the playfulness of the story and led directly to the dramatic irony of the reveal at the end, where the readers finally know more than the boy narrator about what is happening to the balloon.

I had no idea at all how much the decision to experiment with the physical form of the book affected the difficulty and cost of making it until my publisher took me to Italy to see its production. The whole print shop had been re-configured with a long line of machines, all but one of which were responsible not for printing, but for putting the book together.

What themes have you had in your mind when writing for young children?

I tend not to impose external constraints on my writing; rather I let my own playfulness determine the flow and content of a story, trusting my intuition as to what direction the story should take. That way I can better connect to the child in myself and avoid talking down to my readership.

I think playfulness is hugely important, particularly as children encounter an education process which is subjected increasingly to the requirements of tick boxes. Although valuable, assessment is powerless to inspire learning. A child develops in ways more complex than can adequately be described by targets, and those things which do not readily lend themselves to evaluation must suffer by comparison with those that do.

Imagination, for example, is hard to evaluate but is as important as mathematical skill.

That is obviously true for writers like myself, but a healthy imagination coupled with the willingness to take risks also has the power to turn narratives into reality. How else is a potential business entrepreneur to create a new business out of nothing, except by first imagining the possibility?

But if at school things like imagination and risk-taking cannot easily be empirically assessed, and are therefore disregarded as children move towards exams, how are they to be nurtured? The same can be said of empathy, leadership, intuition, verbal communication skills, commercial savvy and so on.

Just as I am wary of limiting the idea of education to those things which can be subjected to external testing, so too am I distrustful of the idea of imposing themes on stories. Let a story find its own path, and if the writer has managed to close the gap between the child in himself and the words he writes, then themes and much more besides will emerge.

Kipper is such a favourite of so many children - what's essential in creating a character that children will love?

I guess children see themselves in Kipper. He does the kind of things that they do; noticing the smell of a beach ball, or becoming besotted with a pet hamster, or seeing how high he can huff his breath on a cold day in November.

An important part of the attraction of characters like Kipper is that they allow children to venture beyond their own limitations. Kipper has no parents telling him what to do. Through him, children can vicariously experiment in ways that are not possible in reality. If he wants to roll in the snow down Big Hill or camp overnight in the woods, he doesn't have to ask permission. That freedom is very attractive for young children who themselves constantly rehearse growing up. Nor is he limited by reality.

Children can travel around the world with him in a hot air balloon or visit the bears under the stairs.

The fact that he exists in the white world of the page itself rather than in a fully realised location or exact point in time allows these different kinds of reality to coexist without contradicting each other. That mix is very close to the way children use their own imaginations when playing. Essentially, he's a more vivid version of themselves.

Your books are used widely in schools. Have you researched literacy?

The short answer is no. Although we used a structured reading scheme to help our own children over the first tricky hurdles, we also read many picture books together.

My own feeling was that the carefully designed progression of the reading scheme was really helpful in creating an easily negotiated learning gradient, while the picture books vitalised the whole learning process and gave it a point. Our kids were incentivised to read because the picture books they read were so much fun and sharing them was such a rewarding experience.

My role is not to teach children to learn to read but to tell them stories. Happily, storytelling and literacy are inseparable.

The Blue Balloon marked the point at which I decided to trust my own intuition when writing for young children. I had some doubt about using a lengthy word like 'indestructible' in the narrative, but felt that very young children would probably enjoy getting their tongues around one or two difficult words, provided they weren't bombarded with them.

A couple of years later a friend told me that his toddler, having been introduced to The Blue Balloon, now enjoyed stomping around the house declaring loudly that he was indestructible. Whether he understood the exact meaning or was just enjoying the sound didn't seem to matter.

As the author of so many books that are favourites with children and families, what were some of your own favourite books as a child?

We didn't have all that many books at home when I was small, so pretty much any book I was given became a favourite. Two in particular I remember.

Jennings' Little Hut was given to me by an aunt. It was about the adventures of a public schoolboy, a world entirely unfamiliar to a boy from Romford, but I loved it.

The second was from a wonderfully written and illustrated Ladybird series. It was entitled What To Look For In Autumn. No prizes for guessing the other three titles in the series.

Comics were our staple, though. My brother and I read the post-war Victor from cover to cover every week, squabbling over whose turn it was to have it first, and leaving the dull, picture-less story till last.

We also had the improving Look and Learn which remained pristine and unread in its specially purchased red collector binder. It was a kind of supplementary educational insurance policy my mum took out for us. We neither looked nor learnt; sadly we scorned it and lusted after The Beano, which remained exotically out of reach, ruled out by our parents. I had great parents - but they were wrong about The Beano.

Topics: Picture book, Classics, Animals, Features

Add a comment