How learning Anglo-Saxon words brought my fantasy books to life

Published on: 01 November 2018 Author: J.R. Wallis

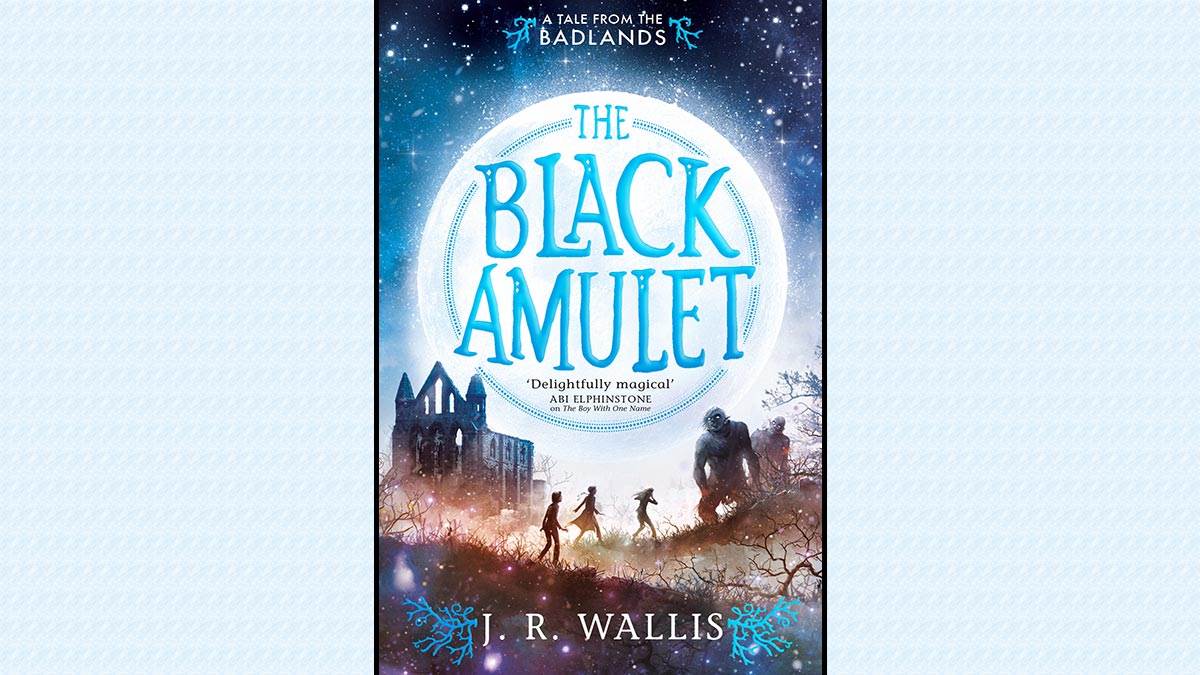

The Boy with One Name author J.R. Wallis is back with the second book in the Badlands series, The Black Amulet. Here, he explains how he made his fantasy world feel real - by learning Anglo-Saxon language...

I used to avoid using research for my stories. I was scared it would act like a brake on my imagination, forcing it to be grounded in the real world, and stripping it of the creativity that allowed me to fly off as an eager fictionaut into unknown places.

But as I've written more, I've learnt the value of research, and how to use it effectively without compromising the spontaneity of writing that I so enjoy. Research can be a valuable key to unlocking the plot of a story when I'm stuck, because even just a tiny detail about something can inspire me to change tack or find a way out of a dead end if I've hit one.

Research has also been vital in helping me create my current series, where monster hunters operate in a liminal place called the Badlands. Despite being a modern day fantasy, I wanted to give my world of monster-hunting a real sense of credibility and believability given the Badlands is somewhere 'on the edge of ordinary people's lives most of the time'.

The books are meant to function as windows into a world that might feasibly exist beyond the pages, so infusing the Badlands and the monster hunters working in it with a sense of realism was important to me. I wanted to give the world some roots in the past, entwining them with my imagination, and decided to use Anglo-Saxon history and language, as an entry in the glossary at the back of the books explains:

'The [Badlander] Order evolved in Great Britain during the 5th century after the arrival of Anglo-Saxons from continental Europe who brought with them their own secrets and methods of fighting monsters. Ancient Britons adopted these techniques as they gradually embraced the culture and language of Anglo-Saxons.'

Discovering another language

Of course, the world of the Anglo-Saxons is a rich one when it comes to monsters and mythology, which is why a book about monster-hunting had a natural link to this time in history for me. But it's the language that really appealed.

It has that sound of the fantastical - of 'ye olden times' - yet the ring of the familiar, too, given that many of our modern words can claim a lineage back to this time. I'm not a philologist, and I'm certainly not Tolkien, but there's clearly an advantage to colouring in a fantasy world with language that not only looks and sounds different to what readers are used to, but also forces them to work to extract the meaning.

I think this actually plays on one of the deep and enduring strengths of all prose fiction - that readers are asked to meet the author halfway in a book, using their imagination to interpret what's written on the page and therefore immerse themselves in a story.

Since I wasn't inventing a language - or, indeed. playing with one as J.K. Rowling did to create the Latin-infused spells that her characters cast in the Harry Potter series - I had an easier time using Anglo-Saxon, following the grammatical rules when I chose to (although there was a healthy dusting off of brain cobwebs about gender and cases that sent me spinning back to my schooldays!)

Knowing when to use it posed an interesting issue since all the magical spells are spoken in Anglo-Saxon and I was wary of using magic as a plot crutch. It also had to work in combination with all the other elements of the Badlander Order, which in my mind had survived for centuries, evolving by keeping pace with the development of the ordinary world and therefore incorporating modern-day words too.

Taking Anglo-Saxon beyond the Badlands...

It's fair to say that while Anglo-Saxon was not an inspiration for the book, it's been a vital element to the creation of the world and the story. But its role hasn't stopped there - there have definitely been some extra benefits since publication.

First, it brings a period of history to the forefront for readers, hopefully without being didactic. Novels have a great capacity to both educate and entertain, by immersing readers into fictional worlds. I recently attended a lecture at the Summer School at Cambridge University given by the crime writer Elly Griffiths, where she made a point that resonated with me about crime fiction being very educational, providing readers with lots of information on a variety of topics from geography to a specific time in history.

A further spin off of using Anglo-Saxon has been the opportunity to open up the English language to readers when I go to schools. It's been interesting to see how easily they can start to trace many of our current words back through time, stripping it down from its Latin and French to a distant period in history - for example, can you guess the meaning of the word clif or perhaps blédan?

There's also the chance to illustrate the the magic that words have - for example, BREÓST-HORD, which refers to the heart and literally means 'breast treasure', or HLEAHTOR-SMIÞ, which means a person who makes you laugh - literally a 'laughter-smith'.

Simply put, it's been very enjoyable learning about a new language for my books. What has been equally interesting to learn is that writing fantasy isn't so much about escapism but reframing our world to look at it afresh; a world that one needs to know well enough in order to twist it into something new using one's imagination.

Add a comment