Getting children interested in British imperial history

Published on: 07 June 2023

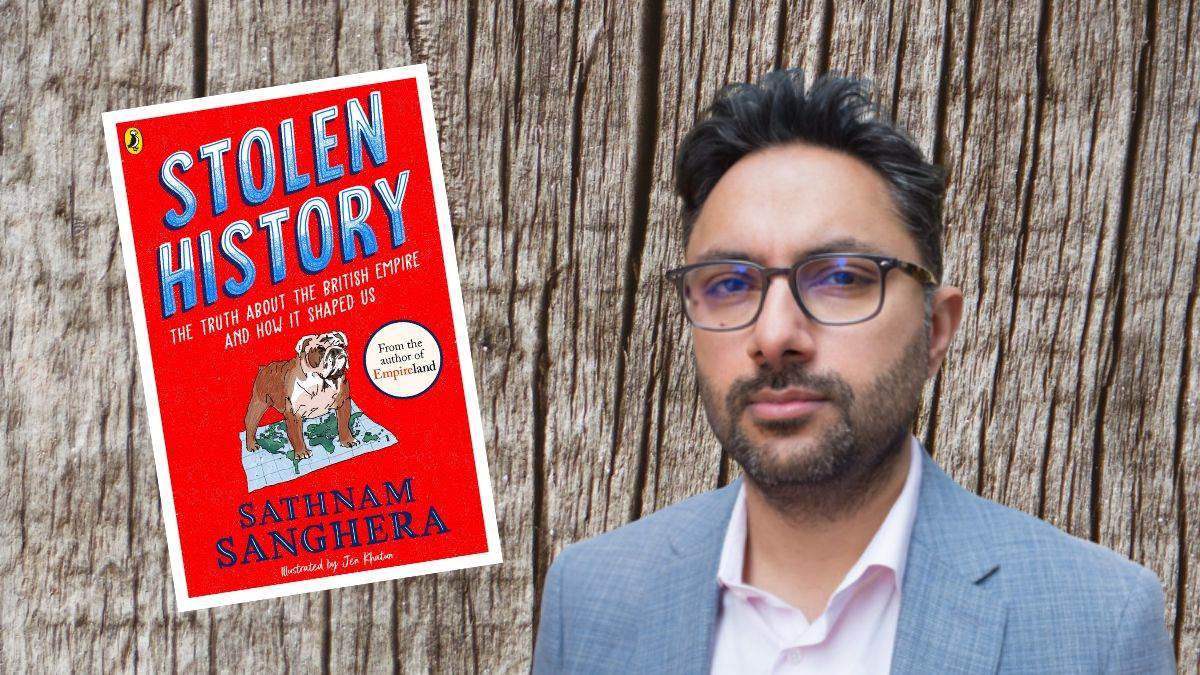

Author Sathnam Sanghera shares why it’s so important to shine a light on this area of British history.

Why is it important for children to understand British imperial history?

You might as well ask why it’s important for children to understand the world around them, because the British empire explains so much about Britain in the 21st century. It explains some of our national wealth (which comes from slavery and colonial enterprises such as the East India Company), it explains the large number of British people around the world (we got about as a result of running the biggest empire in human history), the global prominence of the English language, the importance of the City of London, the popularity of British education, elements of our national and international politics, the role that monarchy plays, our particular brand of racism and the loot that stuffs our museums.

Having not been taught very much at all about British empire at school, it has been a shock for me to discover that it also explains some very specific things about my life. I’m British Sikh, and it turns out that the image of the Sikhs as a military people was shaped and propounded by British imperialists, who trusted them more than other ethnic groups in British India. I studied English Literature at university and it transpires that, counter-intuitively, this subject was being taught in India before it came to Britain. And then there is the simple fact that I am the child of immigrants from the Punjab, which wouldn’t have happened if a bunch of British people hadn’t headed over to India in the 17th century.

The most important lesson for children

Which brings us to the most important lesson for children: the fact that we are a multicultural society largely because we ran a multicultural empire. Britain has long struggled to accept the imperial explanation for its racial diversity. The idea that black and brown people are aliens who arrived without permission, and with no link to Britain, to abuse British hospitality is the defining political narrative of my lifetime. It was famously propounded, of course, by an MP representing my hometown of Wolverhampton, Enoch Powell, who regularly called for the repatriation of immigrants, but it was also taken up by the far- right groups who were so keen to etch graffiti on to Wolverhampton homes and has been spread for decades in press coverage painting brown immigrants as spongers.

In the 21st century it has continued to be perpetuated in the way public figures of colour born in this country are still told to “go home” on a daily basis on social media, in endless talk of “second- generation immigrants” (how can you be an immigrant if you were born here?), in the fact that Shamima Begum, one of three schoolgirls who left London to join the Islamic State group in Syria, could have her British citizenship casually removed by politicians and in the recent Windrush scandal which saw British subjects who had arrived before 1973, in particular those of Caribbean origin, refused benefits, legal rights and medical care before facing deportation.

How can books help?

In short, our national ignorance of empire history is so profound that we have been deporting British citizens to countries they barely know. But this is something every child should be taught. There are now books that can help give children this historical context, whether non-fiction like Stolen History and Black and British by David Olusoga and The Royal Rebel: the Life of Princess Sophia Duleep Singh by Bali Rai, or fiction, like The Elemental Detectives by Patrice Lawrence, or A Nest of Vipers by Catherine Johnson.

If I’d known this history as a child, that there have been people of colour in Britain for many centuries, that there were black people in the courts of Henry VIII, that the first mosque was opened in Britain in 1899, that there were Indian members of Parliament in the 19th century, that millions of black people and Asians fought for empire in both World Wars, I would have felt less alienated. I would have known there were deep reasons for my family’s existence in Britain. And I hope that Stolen History instils British children with a similar deep sense of belonging.

Stolen History by Sathnam Sanghera is out now.

Topics: Historical, Diversity (BAME), Features