How to Train Your Reader

Published on: 29 June 2023

Author-illustrator, and former Waterstones Children’s Laureate, Cressida Cowell shares her tactics for engaging child readers.

My Quest is to create books and to try to get the children of today to read and write and draw with the same excitement and wonder that I did when I was a kid. The 'How to Train Your Dragon' books could really be titled, How to Train Your Reader, because my aim is to take a child who might be a reluctant reader at the beginning of the series and encourage them to love the books SO much that by the end of the 12 books, they’re set on a reading quest of their own.

Not only is there hot competition for children’s time and attention nowadays, books can also suffer from being perceived by children as something old-fashioned, ‘school-y’. In my books I work very, very hard to overturn that impression, by making sure that the stories are worth the effort the child has to put in to access them. The storylines are pacy, and thrilling, with lots of cliffhangers and I pay a huge amount of attention to the visual aspect of the story. Even though these books are for older readers, I pack them with illustrations.

The plots are wildly unexpected, and they rattle along with a roller-coaster energy that is barely in control. This makes things exciting – the reader does not know what will happen next, and you have to make them feel that they might be in the hands of an author who is prepared to give the story a sad ending if necessary. If you know that everything is always going to be all right in the end, where is the tension, where is the drama?

The most important part

The most important thing is to ENGAGE the kid, so absolutely the first thing you have to do is create a character that they care about, because if you don’t do that nobody cares if you drop the character off the cliff. Once I’ve created engaging hero-characters, I want to MOVE the reader, make them laugh, scare a little bit, and make them think.

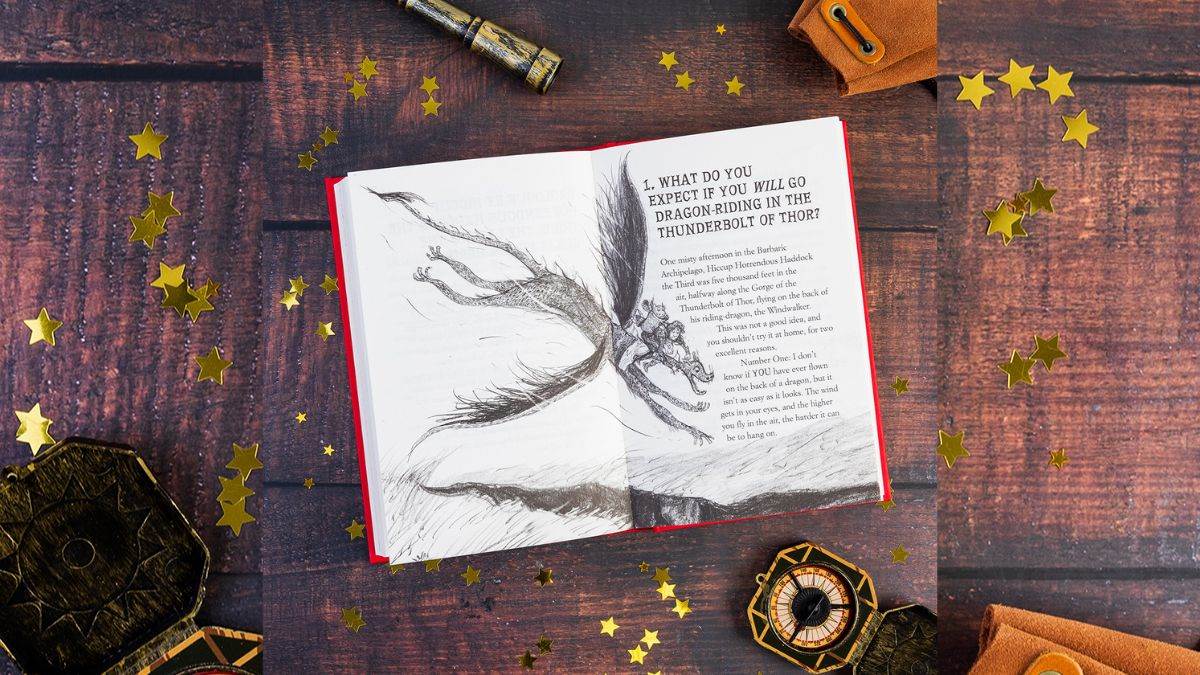

I make the covers friendly and exciting, and preferably shiny and jewel-like, so that in the mind of the child they are ‘sweets’, not ‘Brussels Sprouts’. The illustrations are deliberately child-like and scrawly, and look like something the young reader could do them themselves, which is important to me because I want to get them writing as well as reading – that’s why so many of the illustrations are in pencil, as well. There’s also a lot of movement in the drawings, usually to the right, because I am literally pulling the child to turn the next page.

You might also notice that the books become slightly longer as the series goes on, the illustrations more world-building and dramatic. Again, this is developing the child’s skills as they are reading through – no decision I make about my books is an accident.

The importance of reading aloud

I write the books to be read aloud, and that is a key factor in getting a child to read for pleasure. Books read to you in your parents’ or teachers’ voice live with you all your life. Reading a book aloud is a shared joy, and sends an important message to the children being read to: books are important, books are powerful, magical things, that can make your dad cry, or the whole class laugh, and have the sort of wisdom in them that can change your life. With reading-aloud in mind, I think about the books as a performance, and the mouth-feel of the words, the loudness or softness, or bellow-y ness of the characters.

And I never EVER dumb down. Children are natural philosophers, naturally curious, natural linguists. My job is to engage the questioning spirit of children, so these are the kind of questions I’m asking the kids in these little fantasy books about dragons and wizards: do we live in a world of determinism or free will? What makes a good parent? How should we look after the environment? Is it ever justifiable to go to war?

Playing with language to engage readers

This all sounds rather grand, but I take a lot of care to present it as fun. Take the Dragonese for example. It can just be enjoyed because it’s a very silly language that says things like: ‘mi mamma na likeit yum-yum ondi bum’, which means: ‘my mother does not like to be bitten on the bottom’. But there are other ways the language is used to get them to think about things from a different angle.

The Dragonese word for window is ‘air-square’, which invites the reader to think. A window is the ‘frame’ that shapes the window, but it is also the square of air inside the frame. Many of the words force you to see things from a dragon’s point of view; mice are ‘squeaky-snacks’, dogs are ‘dimwoofs’, love is ‘esallrightreely’ because dragons aren’t really into love. By putting in those words I’m encouraging children in empathetic thinking.

Creating for children is often a balance between having the courage to take something silly and make it serious and meaningful, and taking something serious and having the courage to make it a bit silly.

Training creators as well as readers

In training readers, I’m also training creators. Children have an explosive enthusiasm, a need to express their ideas, and a talent for innovation that surpasses a lot of adults. We know from decades of research that the huge, long-term benefits of reading for the joy of it are life-changing. For every percentage point your literacy level goes up, you’re more likely to be happier, healthier, wealthier, more likely to own your own home, more likely to vote, more likely to not be in prison. BookTrust research suggests that reading for the joy of it is one key indicator in a child’s later economic success, irrespective of what background they are from. Training the readers and creators of the future is a necessity, for all of us.

It is the 20th anniversary of 'How to Train Your Dragon' series in 2023. All books are available now.

Topics: Features, Cressida Cowell