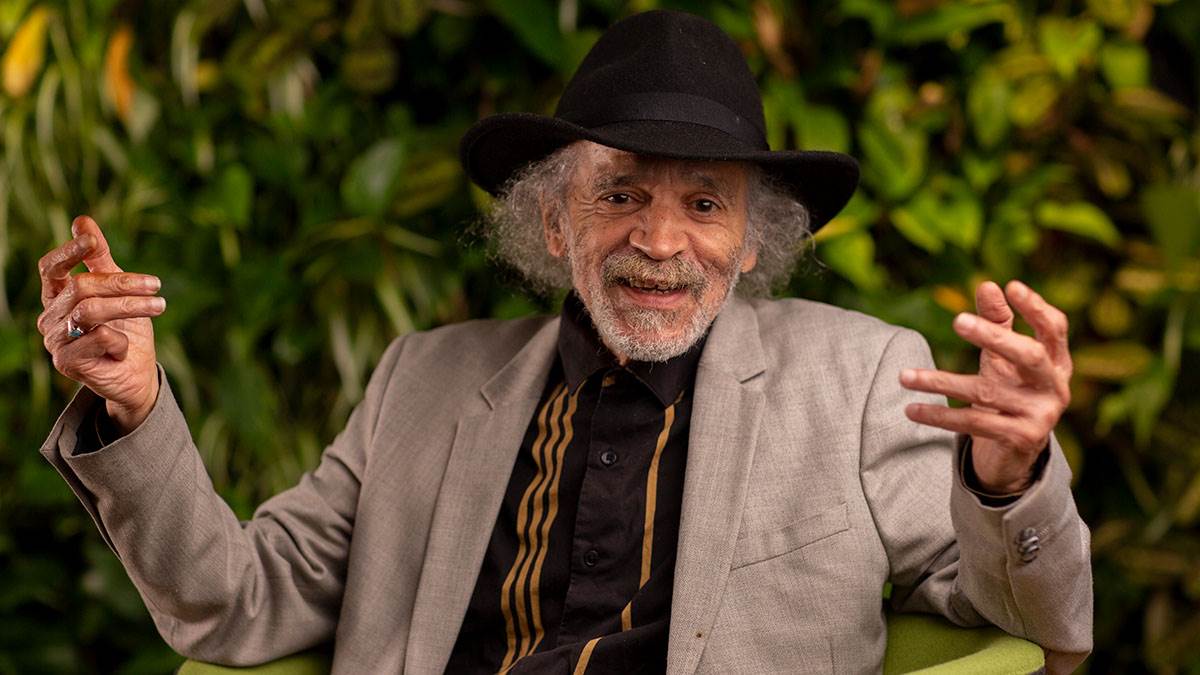

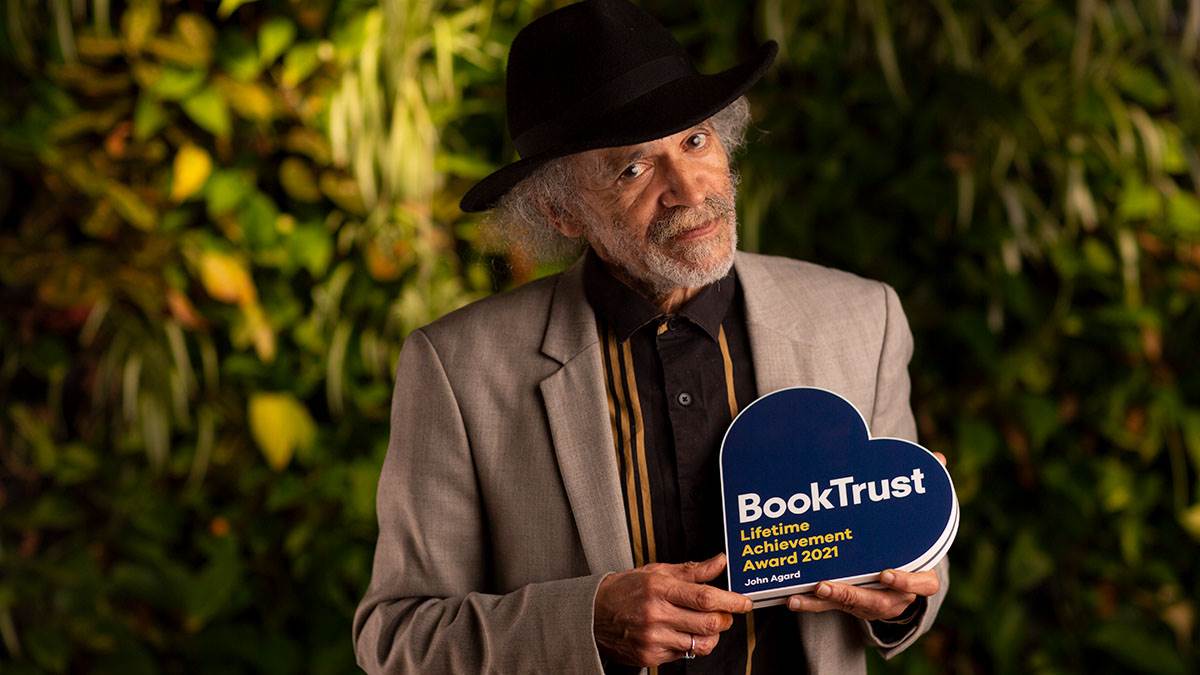

'We are all creatures of language': Lifetime Achievement Award winner John Agard on his incredible life and career

Published on: 09 November 2021 Author: Emily Drabble

John Agard has been crowned the winner of our 2021 Lifetime Achievement Award! Here, he talks to Emily Drabble about the power of poetry and how it feels to receive the Award...

John Agard was born in 1949 in Georgetown, Guyana (then called British Guiana). He moved to England in 1977 when he became a touring lecturer for the Commonwealth Institute to promote a better understanding of Caribbean culture.

Over the course of the next eight years he visited 2,500 schools and started writing poetry for children. Since then, he has published more than 50 books of poetry, stories and non-fiction, and has co-edited anthologies with his wife Grace Nichols. He won the Queen's Award for poetry in 2012 and his poems 'Half Caste' and 'Checking Out Me History' have been on the GCSE curriculum since 2002.

First of all, John takes us on a trip down memory lane back to his very beginnings as a poet...

Looking back to my childhood, I didn't tell myself I would be a poet but anything that pertained to language interested me. Don't forget, Guyana was a British colony, so I had all these influences.

Whereas now a young teenager may pretend to be a rapper and strut their stuff in front of the mirror, I would pretend I was a cricket commentator and create a fictitious commentary using words such as 'majestic' or 'magnificent' in the style of the legendary cricket commentator John Arlott.

I'd read Enid Blyton - it might be Five go Down to the Sea. Blyton might use the word 'flabbergasted', or the word 'consternation'. I'd say words out loud – 'preposterous' - it just sounds good in my mouth! I'd read The Hardy Boys. And then I'd go to the market and get in Calypso and vibrant Caribbean Creole, which can be so spicy and so bawdy.

We would shift gear, shift registers of speech, but speaking English all the time. There were all these different strains of language emerging in me. But I didn't know I would be a poet yet.

What were your school days like?

I went to a Roman Catholic Jesuit secondary school in Georgetown called St Stanislaus College, and was taught mainly by priests. My favourite teacher was my English teacher Father Maxwell, who made the dictionary an adventure. I became an altar boy, so I had to reply to the priest in Latin, and that had a magical liturgical song about it.

The school had a fascinating tradition of inviting one of the boys to read to the priests from a book every day. So imagine me standing there as a 13-year-old reading P. G. Wodehouse, putting on an imaginary flamboyant tie as Bertie Wooster! Of course, I wasn't conscious of class in the English sense. Friends of mine now with a working class background would dislike that type of thing but to me, I'm just seeing the language.

At the age of 14, I joined the Junior Dramatic Theatre Guild. I got the part of Captain Hook, and went on to become the White Rabbit in Alice in Wonderland and Feste in Twelfth Night.

I got excited by anything to do with language. We had a tradition of elocution - you had to recite a poem in front of your class. I was in love with this. I had an obsession with being an actor but my mother said, 'Acting is a hobby.' She pointed to a friend who was working in the bank with a decent job.

When did you write your first serious poem?

I wrote my first poem in the Sixth Form during my exam. Picture me aged 16 writing this on my exam paper:

'Sitting in my classroom cell.

I chew my pen as words come tumbling down on printed lines before my eye.

Oh, Wordsworth, why were you born to wrack my brain with songs of praise to lifelong nature?'

I failed the exam, but a teacher, a white teacher called Michael Gilkes, fresh out of Oxford, said, 'John, well, you wouldn't pass your exams by scribbling poems at the back of the exam paper. Having said that, I like this poem'. And one thing led to the next - he spoke to colleagues at neighbouring schools and got other teachers involved. This shows how a teacher can give you that sort of desire and feed you!

And this poem was published in a magazine called Expression 1, printed on this dinosaur machine called a Xerox. Then Expression 2 was published and later when we were around 18 years old, we young poets would meet, and Expression 3, 4, 5 6 were published and so on. I have some old copies of these and I treasure them. That humble situation was the springboard for many of us to go on to pursue wonderful academic careers, become novelists and published poets.

Authors and illustrators on why they love John Agard

After leaving school at the age of 19 after his A Levels, John taught French and Latin at O Level for a year and then got a job as a librarian, in the same library where he had borrowed his copies of Enid Blyton and The Hardy Boys when he was a child. He was commissioned to manage the mobile library, going to the outer districts of Georgetown and says now, 'That was a wonderful time in the Book Mobile, it was the best job ever. It was like a holiday!'

What is it about poetry to reach parts and people that other art forms might not reach?

We are all creatures of language, so whether you live in a deserted desert and have never seen a movie, or live in the far reaches of the Amazon and have never heard of an opera, or are a Yoruba farmer, gathering yams in West Africa - you have heard your mother speak to you. You heard your dad speak to you. You've heard a lullaby.

Bear in mind that before books were written, poetry was part of a day to day ritual. So, with due respect to the magic of opera or the brilliance of a movie, we are creatures of language. We all have a diversity of languages. And before poems were written down, they were sung. There were Irish charms for milking a cow. Poems by the Inuit for caribou hunting.

A lot of oral poetry is keyed into our heartbeat. The words you hear at your mother's lap. The utterance of words in the right order can excite, be thought-provoking. We are so surrounded by language if you get tuned in. And I would like to think in my biased way that poets return us to the complexity and the fragility of language and by the same leap, the complexity of us as human beings and our fragility.

Poetry liberates you to the musicality of language, to which we were born with that heartbeat, but also the joy of words which we all have.

You write poems for everyone, but what has drawn you to focusing on writing poems for children?

I came to England on 4 November 1977, and in 1978 I got a job at the Commonwealth Institute as a travelling lecturer visiting ten schools a week for eight years - eventually I visited 2,500 schools. I was the Man from Guyana. I started to realise that a little poem could make the talk exciting, so I started writing poems for them. So that's where it started.

Why are libraries important?

Libraries are crucial because a school librarian or a public librarian, simply by directing an eager mind in the right direction of a book, could change your life. Librarians get the books to the children who read them.

You might be a librarian who is simply an employee of a library, or you might be one who is a bit eager and sees a mixed race child and says, 'Have you read this book by Jackie Kay, she has a Nigerian dad, I think you might like that, come with me.'

And if that child never experienced a book outside of white writers, well, the librarian can change lives. Librarians, booksellers, teachers, they're all part of the magical linking from utterance to something life-affirming and even life-changing: the book.

How big is the impact of meeting an author and poet on a child?

I would only have realised that by coming to England because in our school days, we couldn't meet the writers we loved. There were dead.

But much later when I was standing outside a pub in Nottingham a young woman in her early 20s came up and said, 'Are you that bloke that wrote Half Caste? I heard you and because of that day I wanted to do creative writing.'

She had attended one of the GCSE poetry live gigs which have allowed thousands of teenagers from Coventry to Nottingham to Dubai to meet the poets they study. So I can't deny the fact that the live performances and visits are exciting and impactful.

From 2002, John's poems have been on the national curriculm and widely studied in schools, and he's been doing GCSE Poetry Live shows, meeting thousands of pupils across the country.

John, what do you think about the latest statistics that show only 1% of GCSE students in the UK study a text by a writer of colour?

Let's put it this way, the British superstructure may not be as aggressively racist as America and United States. But there are subtleties, maybe even subconscious perceptions, that make them feel more at ease with racism.

Bearing in mind that many colonialists felt Africa had produced no literature, it was all about the West - a jump from Homer to Jane Austen. If you are potentially tribally blind, and some of these guys who might be Ministers of Education might have come from a rugby college and Oxford aristocratic background, whether they like it or not they have absorbed within their DNA a paternalistic, condescending attitude towards so-called, in inverted commas, 'exotic natives'.

So the brilliant boxer, he knows his place. You celebrated it. Attitudes get more ambivalent when the mind enters the arena. Don't get me wrong, you will have many who are humble enough to say, 'I never knew this existed. I must re-educate myself. I must re-condition myself.' But it's very perfidious and it's very insidious.

How does it feel to win the Book Trust Lifetime Achievement Award?

This has come out of the blue from BookTrust, an organisation that takes books to heart and is very, very knowledgeable about the tremendous wealth of writers, thinking about those who have won before: Judith Kerr, Shirley Hughes, Raymond Briggs, Helen Oxenbury, John Burningham and David McKee.Apart from being the spring chicken of the group, it excites me that they have chosen poetry as I'm the first poet to win.

I got the good news about the Award at a time when I needed the good news. How could I not be excited? Because when you write a book you write in solitude. And then to think of somewhere like the BookTrust, who treasure books and who try to make books part of a life-enhancing experience for a child...

To hear the judges were saying these fancy things about me... I feel happy that I've stuck with this craft from that 16-year-old boy writing in a classroom in a Caribbean ex-colony. What goes through my mind is that it's not just me, but all the people that inspired me. If only my teachers could be there... I'm thinking about who published my first books, who contributed to my journey way back in the Caribbean, my head is back to John Arlott, the legendary cricket commentator!

This thing called poetry has power and I stuck with it and I still get excitement from language. Just finding that joy in standing in front of people and saying a poem. I know this thing connects. This thing could touch a soul. This thing doesn't have to be didactic, I don't have to preach to people. So my whole brain is on a tidal wave of delight.

All photos © David Bebber

Topics: Poetry/rhyme, Lifetime Achievement, Rhyme, Interview, Features