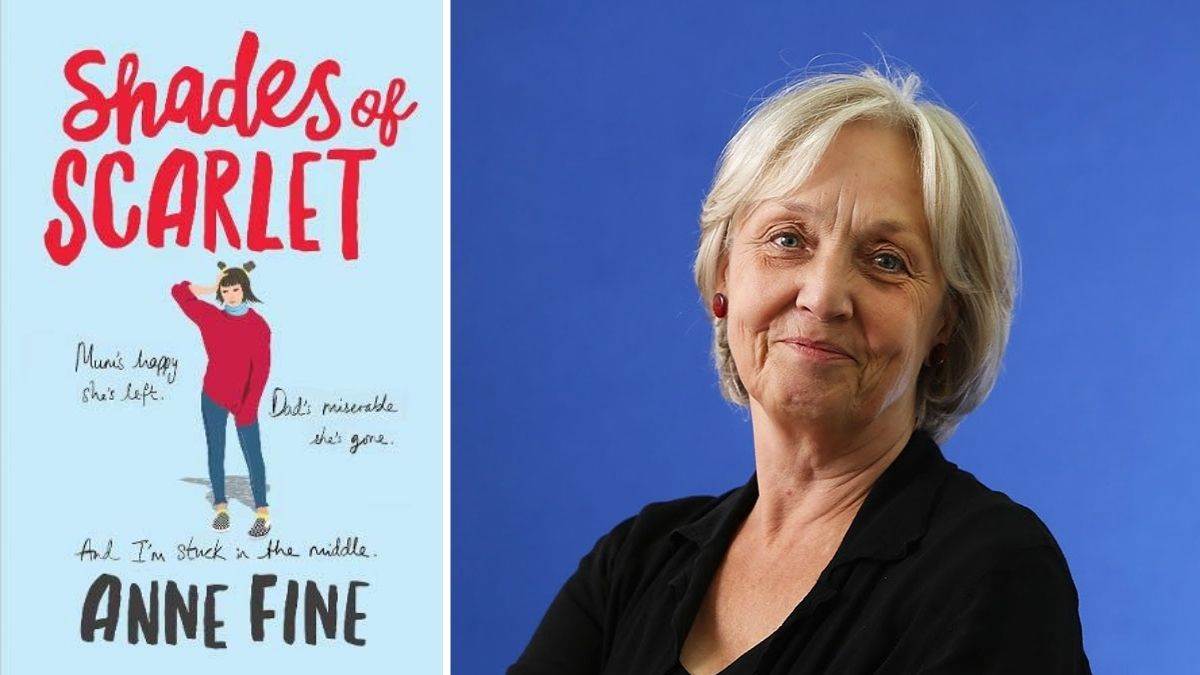

Shades of Scarlet: Anne Fine on talking to children about separation and divorce

Published on: 22 March 2021 Author: Anne Fine

Shades of Scarlet is about a girl navigating the emotional impact of her parents' divorce. Author Anne Fine shares some of her own experiences in writing about these topics for children, and reiterates how allowing children their own feelings can help them adjust to a different family life.

There are no villains

Writing Shades of Scarlet was a pleasure because, unusually, I'd chosen to write about a girl who's tough and smart and sensitive enough to not only realise what's happening around her during her parents' separation, but basically equipped, with only a few wobbles, to deal with it well and come out not only more mature, but smiling. It helps, of course, that there are no villains in this novel, no outsiders who know or care so little about young people, that they make things even more difficult than they would be anyway.

I used to be surprised that divorced families are seen almost as 'Anne Fine's literary stomping ground'. Looking back, I have, statistically, only the same percentage of split families as are around us. But these particular books have definitely gained more notice, and gathered many more readers, along the way.

I don't believe I'd given any thought at all to the children of divorce until we came back to Scotland after three years abroad. In the Californian school my children attended, divorced parents sat together at concerts and meetings, changed arrangements to suit one another's schedules and happily ferried cellos and tubas from one house to the other. I know these marriages had often been little short of fleeting, and the Scottish parents surrounding me on our return had usually invested years more in their marriages before giving up. Still, I was shocked by the frequency of the attitude: "Well, if your father will be there, don't expect me to come too."

I wrote Madame Doubtfire to show how, after divorce, the only excuse for contact between the parents is to make life easier, not harder, for the child. But in the book (unlike the film) there was no step-parent figure to complicate matters.

The cover of Madame Doubtfire by Anne Fine

The cover of Madame Doubtfire by Anne Fine

Blended families can work brilliantly

Nonetheless, Goggle Eyes has one by accident. I wanted to show both sides of a then very live argument about nuclear weapons. How better than to have Kitty a committed campaigner, and Mum's new partner to be of the opinion that these weapons had kept the peace for decades and should be valued? (Today, of course, Kitty's sympathies would be for Extinction Rebellion; but most of the political arguments in the book still resonate.) I was fascinated to find most readers responded more to the emotional development in this Carnegie winning book. But I was deeply disturbed by the number, and force, of the letters I received from young readers. "The end of your book was a total cop-out. I have a stepfather (or mother, or brother, or sister) and I will never get to like him."

We all of us know that separated and blended families can work brilliantly, with many intractable problems born of unhappy marriages relaxed or removed.

Still, all those children who'd written to me, so unhappy in their own homes! It set me writing Step by Wicked Step, a collection of stories about the children of separation and divorce. Some of the families make it work; some don't. It's based on a huge amount of research reading, and proved in places, emotionally, the hardest book I ever wrote, by far.

Allowing children space for their own feelings

A worrying feature was learning how difficult it could be when a parent determinedly attributed their own feelings to their offspring. In a typical case in one particular study, a mother might claim, "Oh, Maya was very unhappy when her dad first left. But since Greg came to live with us she's been much happier." But it's all too easy, especially when you yourself are in upheaval, to see what you want to see and hear what you want to hear, because the researcher who interviewed Maya might separately report the child as saying, "I still cry every night, but I don't say anything to Mum because it might upset her."

The cover of Goggle Eyes by Anne Fine

The cover of Goggle Eyes by Anne Fine

Another mystery for me was why parents seemed so quick to believe the frequently voiced theory that 'children blame themselves for the divorce'. Not in my experience, they don't. They know only too well exactly where to lay the blame. It's just that when the rock on which they stood has already shifted so badly, few children probably choose to set off further wobbles by coming clean with what they really think.

So when Mum gives her the lovely blank book, small wonder Scarlet's suspicious. A simple gift? Or is it to tempt her into keeping a diary, so Mum can keep tabs on what's in her daughter's mind? It raises an interesting question, because so many of my books involve the business of children writing down their own accounts of what has happened to them. Why is this? I suspect it's because we all know from experience that it is really, really hard to write lies. Think of the Christmas cards you've started to put a bit of news in, and then, as it pours out on the page in front of you, decided, "No. Don't feel like going there. Not now. Not yet."

How reading together can lead to talking together

I have no doubt that parent and child reading a book in tandem invites and stimulates honest discussion. "That's exactly how I feel!" "It's not been at all like that for us, has it?" That's all to the good. I have so many letters from parents saying how much my books, shared, made it easier for the child to bring up things that were worrying or upsetting them, from the important ("Dad's girlfriend never, ever leaves me alone with him, not even for a moment.") to the more trivial ("Stop calling her 'your mother' as if she's never, ever been anything to do with you!")

That stuff can be willingly shared because reading about other people's problems helps anyone approach the similar ones they themselves face vicariously and safely. But it's my view that children need their privacy.

I wouldn't write a diary - ever - if I thought my mother might read it. It's not that I don't think writing out your problems isn't really good therapy. It is. And by the time that Scarlet comes to tell her story, she has the sense of proportion that tends to grow only with time.

But don't make the mistake that Scarlet's mother makes. If you buy your child a lovely blank scarlet book to use as a diary during the maelstrom itself, then lash out a little bit further and buy them a strong tin box with a good padlock as well.

Topics: Family, Fathers, Mothers, Personal/social issues, Everyday life, Relationships, Features, Feelings