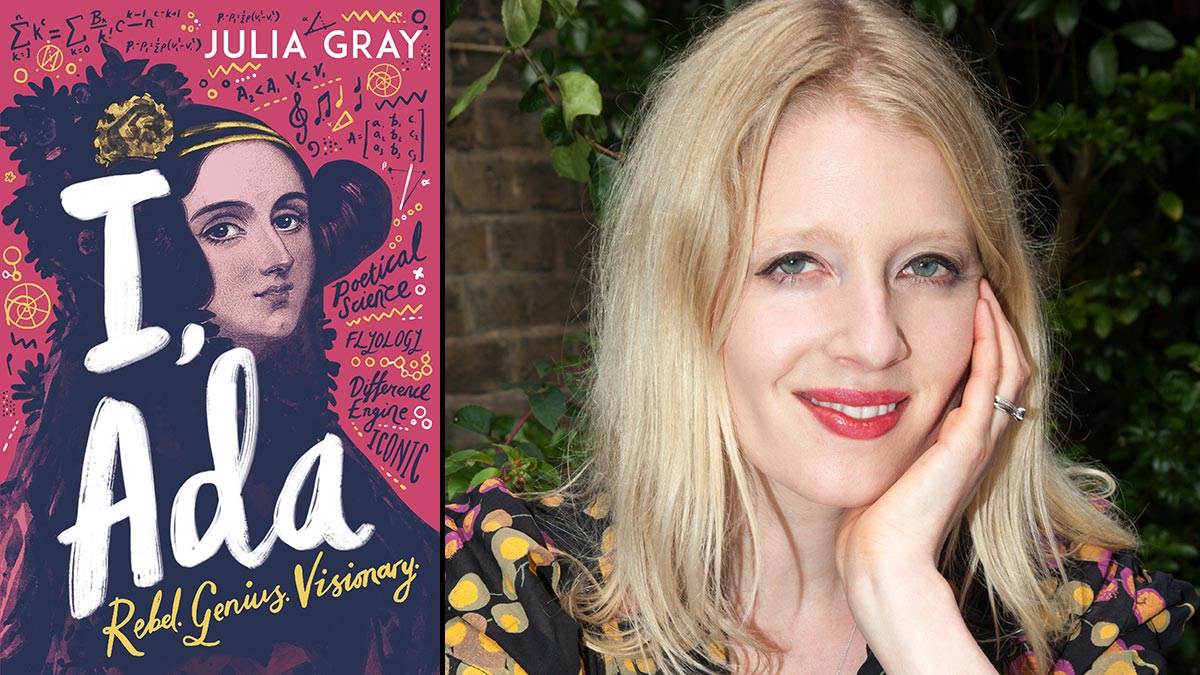

I, Ada author Julia Gray: Why children need stories about incredible women in STEM

Published on: 30 September 2020 Author: Julia Gray

When she started researching Ada Lovelace's life, author Julia Gray was blown away. Here, she explains why it's so important for children to have stories of inspiring women...

I don't think I read a lot of biographies as a child. Although I had a book that I loved about Helen Keller, the majority of the biography books I owned were about men - kings, composers, explorers. Certainly, I never read about female engineers, scientists, inventors or mathematicians. I wish I had.

I don't think I read a lot of biographies as a child. Although I had a book that I loved about Helen Keller, the majority of the biography books I owned were about men - kings, composers, explorers. Certainly, I never read about female engineers, scientists, inventors or mathematicians. I wish I had.

When I first began researching Ada Lovelace in 2017, I was struck by a kind of wonder at what she managed to achieve in only 36 years.

Ada was the daughter of the poet Lord Byron and Annabella Milbanke, a talented mathematician. The marriage had not been a success and Annabella had taken her daughter away at the age of six weeks - Ada never saw her father again. Although girls did not usually receive any kind of formal education, or go to university, Annabella made sure that Ada was tutored in a range of subjects from an early age, hoping in part that a rigorously structured programme of learning would prevent Ada from developing worrying poetical tendencies inherited from her father.

By the time she was a teenager, Ada could speak several languages and was already an accomplished mathematician, combining a steely desire to deepen her knowledge with a passion for asking questions. (She also had a strong independent spirit and a romantic streak that Annabella's best efforts had not managed to diminish.)

It was a time of growing industries and rapidly-advancing technologies. As a debutante in London, she was introduced to Charles Babbage, who was working on an automated counting machine that he called the Difference Engine. Powered by steam, it would, he hoped, eradicate the problems caused by human errors in the existing tables of calculations. With her impressive knowledge of maths and her ability to grasp the heart of an idea, Ada was thrilled by his designs and a friendship developed between the two.

Ada married Lord King, later the Count of Lovelace, in 1835. She continued nevertheless to work on mathematics and to correspond with Babbage, who was still trying to secure enough funds to bring his plans to fruition. His newest project was a machine called the Analytical Engine, which would be able to use each calculation as the basis for further calculations, a far more complicated proposition.

Ada was commissioned to translate an essay on the Analytical Engine written by the engineer Luigi Menabrea in French. Aged only 26 and a mother of three, she devoted herself to this task, not only producing an excellent translation of the essay but also, crucially, contributing her own extensive notes at the end.

She speculated that the Analytical Engine could be used not only for numbers, but also, for example, to compose music, visualising in essence what the modern-day computer might be like. She also produced a chart that demonstrated how the Engine could in theory process a sequence of 50 Bernoulli numbers – this, in effect, is the first-ever example of a machine algorithm, and the reason why Ada is often called the world's 'first computer programmer'.

The importance of sharing women's stories

Illustration: Emily Rowland

If the first thing I felt on reading about Ada was wonder, the second was surprise that I had never really known her story. Today, Ada Lovelace is rightly celebrated in all kinds of formats, and I am always delighted by how much the children I meet know about her.

Biography is an enormously popular segment of non-fiction for children (in 2018, for example, biographies accounted for 22 of the top 100 best-selling children's titles). The stories of women like Marie Curie, Emily Roebling, Chien-Shiung Wu, Annie Easley, Rosalind Franklin, Dorothy Hodgkin and, of course, Ada Lovelace are widely available and accessible.

Writing and researching my own book about Ada, I became ever more impressed by her determination, passion and brilliance - and was also able to find out more about Florence Nightingale, Mary Somerville and Caroline Herschel in the process, as each of these notable women is mentioned in the book.

To mark the publication of I, Ada, my publisher, Andersen Press, came up with the delicious idea of doing a podcast series – On the rADAr: Conversations with Extraordinary Women in Science.

I interviewed five women who have fascinating careers in STEM: creative scientist Dr Shama Rahman; neurologist Dr Suzanne O'Sullivan; biologist Dr Vanessa Lowe; rheumatologist Professor Tonia Vincent; immunologist Dr Susanna Bidgood, and in November at the Richmond Literary Festival we'll be recording a special live episode for which my guest will be broadcaster and statistician Timandra Harkness.

I am very grateful to all my guests for sharing their stories with me: explaining how they came to choose their particular pathways; describing the challenges and the joys and the minutiae of their jobs; and telling me about the qualities that they think are the most important for their chosen lines of work.

All over the world, women still remain under-represented in STEM fields. To be able to read and hear about the achievements of women in those fields, both historically and currently, makes a critical difference to the girls who might otherwise grow up believing these pathways are not for them. I hope these stories will continue to be told.

Topics: Non-fiction, Historical, Science, Features

Add a comment