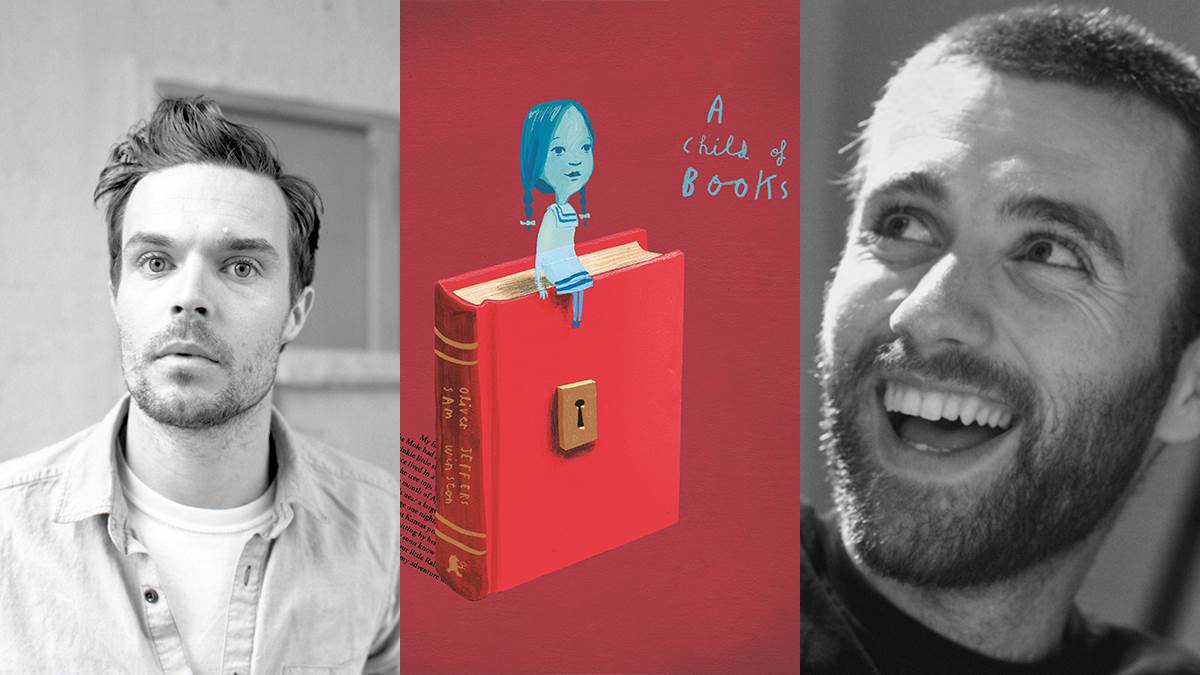

Oliver Jeffers and Sam Winston interview

Published on: 01 September 2016

Oliver Jeffers and Sam Winston talk about their new collaboration A Child of Books, translating stories, and their favourite 'classic' children's books.

A Child of Books is a wonderful and beautiful book about how we are formed as young readers (and throughout our lives) by what we read - what was your absolute favourite book as a child?

Oliver Jeffers: The idea of being formed as a young reader is interesting, because I always remember being a reluctant reader in school. I didn't like having to do something because I was told to. So there were various books that, with hindsight, clearly had an impact on me, but that I didn't enjoy at the time because I was told to read them.

The first book that I remember choosing to read for myself was The BFG by Roald Dahl. I felt like I was being let in on a secret, that wow, these things can actually be really entertaining.

Sam Winston: One that was special to me as a child was In the Night Kitchen by Maurice Sendak. There's something surreal about it, this other world, this alternate space where you don't totally have to get it on logic. It's not something that makes sense in your head. It's much more your gut or your heart. You kind of just go, yeah, of course I'm going to be flying a plane made out of pastry. That's how it is, and that's how it should be.

I would also like to add to what Oliver says about being a reluctant reader - being dyslexic led to a long and labour-intensive introduction to the world of literature. It was a genuine effort but I think the mysterious relationship between word and letterform, and how a whole world comes out of that pairing... that pulled me in.

As we understand it, the foreign language editions of A Child of Books will feature text-as-art from stories belonging to the country of translation in some cases, which, in turn, will be designed by you for every different edition. That's a huge task! What's the most important issue in translating stories, do you think?

OJ: I'm not sure they will be translated per se. We are finding that co-editions publishers are really embracing this book, and that means getting to the heart of it with gusto. We are discovering that publishers are suggesting different stories, relevant to their cultures and recognizable to their audiences that fit in with the essence of each specific spread. This is much better than a straight translation.

SW: Yes, we've found most co-editions publishers want to change certain stories so they are culture-specific. Actually, the 'sleep in clouds of song' spread seems to be the most replaced, and I am presuming this is because lullabies are very regional and more form an oral tradition, as opposed to the classic books that can perhaps travel a little further.

And yes, it's a huge task more akin to an orchestral movement - many people, countries, organisations and languages all needing to create a seamless whole. It's been amazing to see how this project has already captured the imagination of so many and how much enthusiasm it's generated.

What were your aims in creating this book? What do you hope a child thinks and feels when reading it?

SW: The core of the idea of the whole project is in the final line of the book: 'Imagination is free.' If anyone, adult or child, walks away and takes ownership of their own creative process, that's a job well done for us. That's what I think great work can do - when we read the classic texts that we've put into A Child of Books, when we look at art, we're inspired to want to do something, to make something. To be generative ourselves.

OJ: Ultimately this book is an ode to literature, a love of literature that both of us share. We both felt that journeying back through classic literature as a way to explore imagination, and as a way to put the spotlight back to some of these stories, was a worthwhile thing.

Storytelling is a hugely important part of identity, in the stories that we tell, and in the stories that we're told. Our book is partly about that, and it's partly about introducing timid readers to unlocking their imagination. These classic books have helped our imaginations flourish and be defined the way that they are, and we wanted to share them.

SW: Building off of what Oliver's saying about the imagination element and the narrative element, and identity forming, I think we're in a really interesting time at the moment. I think that what we were doing with this project was taking some of the best qualities of what happens in literature, which are storytelling and myth, and combined that with the fluidity of text and language that have come from the advent of digital. We've built those into the kind of story that you can follow in a linear way, but one that also has multiple readings.

A Child of Books references many traditional tales and classics. What is your favourite children's book?

OJ: Gulliver's Travels is a favorite classic of mine, having grown up in Belfast. Jonathan Swift was in Belfast, living on a street called Lilliput Street, and looking up at the cave hill, which looks like a sleeping giant. It's very clear that that's where the idea came from. And this was the city I grew up in. So seeing what this book became and then seeing the origin story of that was a magical thing to me as a small child.

SW: I think I liked books that I didn't really get as a child. One of them was The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. I loved the story. There's something quite unreal about the main character, and as a kid I don't think I fully understood what I was reading. Even as an adult now, when I look back at The Little Prince, I still think there's something otherworldly about it.