Mary Hoffman: why children need more diverse books in the world

Published on: 22 September 2016 Author: Alex Strick

Mary Hoffman burst on to the children's book scene over 40 years ago. Ever since, she's been making sure stories represent us all.

We caught up with the writer to hear why this is so important to her - and how, even today, we still need more children's books that do this.

So far, you've written over 100 children's books. Has it always been important to you that your stories reflected different families, backgrounds and lives?

Yes. My first published picture book was Nancy No-Size [in 1987], about a little girl in a mixed race family. My own husband is half-Indian, and between our and his sister's family, there were five girl cousins who were quarter-Indian and had a range of skin tones.

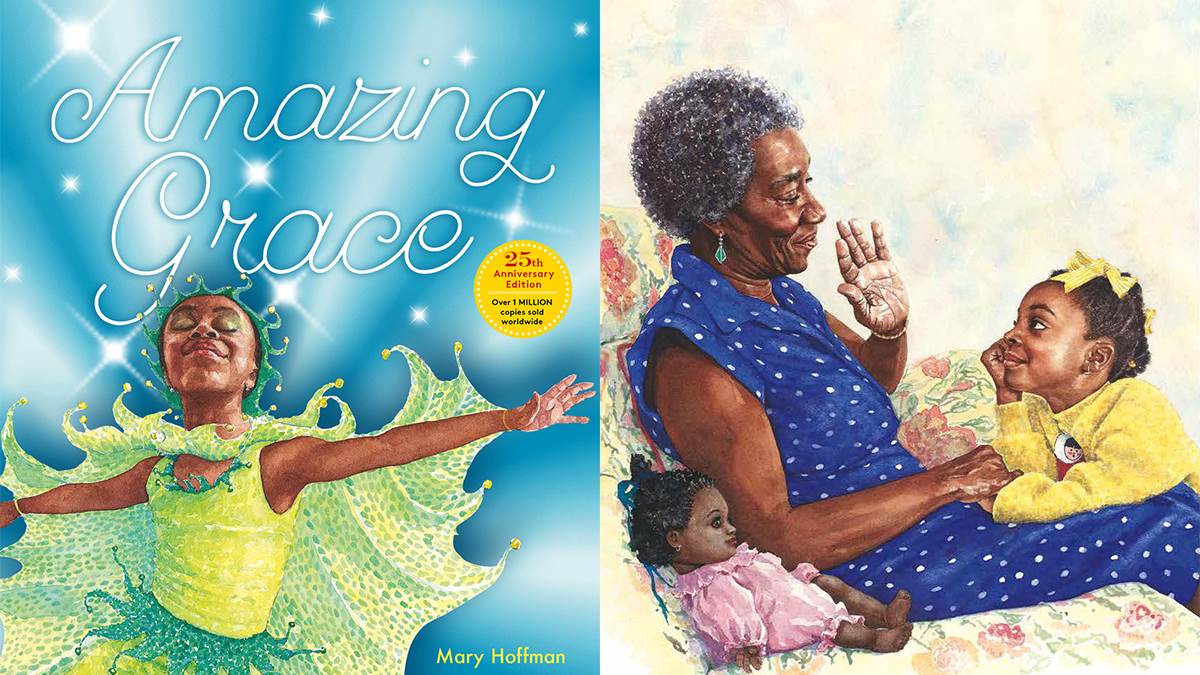

A few years later came Amazing Grace, which was groundbreaking in so many ways. As well as a black protagonist, it features a single-parent family and a powerful message about gender equality...

Now Grace is over 25 years old, how do you feel things have changed, in terms of diversity in children's literature?

Not far and fast enough! But that's true of the society it reflects. When I realised I was a feminist over 35 years ago, I never thought that we'd still be arguing for equal pay for equal work in the 21st century. Or having to legislate against FGM. Or taking away benefits for disabled people and the poor.

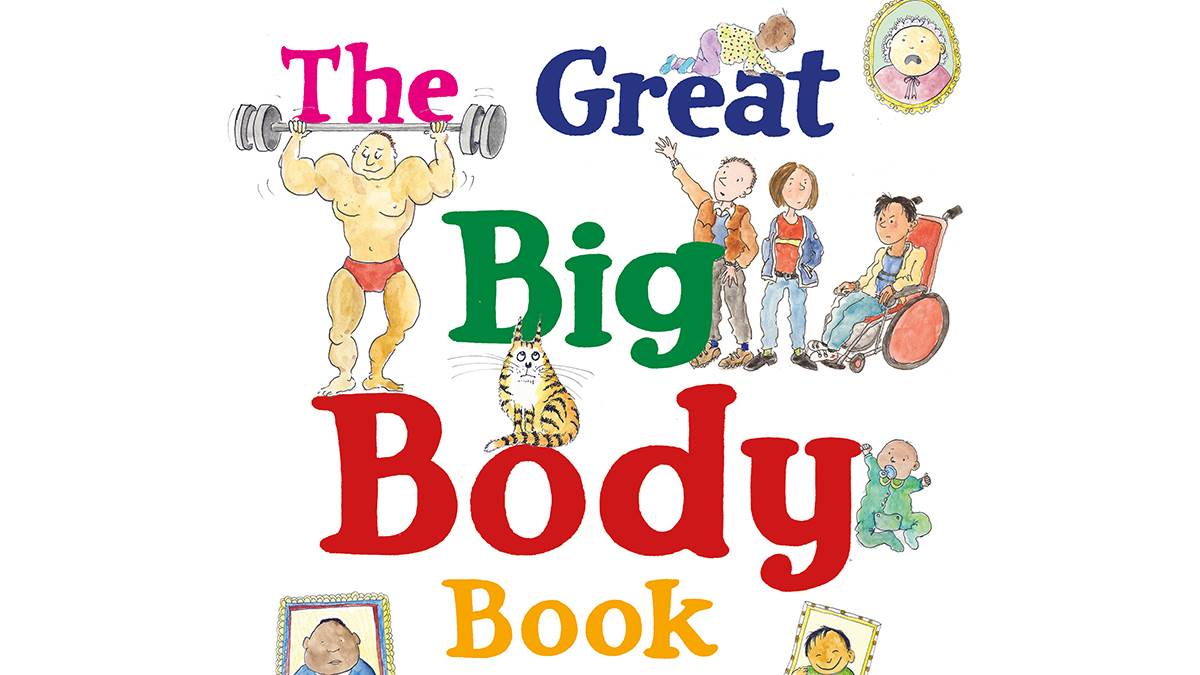

How did the idea for the Great Big Book series first develop, and how important was it that Ros Asquith was your illustrator?

I had wanted - for a long time - to write a picture book that reflected the wide range of actual families in our society. Ros was crucial to the whole project. I had met her a couple of times and believed she would understand what I was trying to do politically. And I was dead right!

The series continually builds on the range of disabilities included, going far beyond just the occasional wheelchair. Is this something you and Ros discuss in your plans for each book or does it happen organically?

We do. Ros is also a writer and I (although not an illustrator) have a visual imagination. So we have meetings to talk through the topic and what the spreads are likely to be.

We talk about a range of disabilities, as well as race, sexual orientation, gender identity, family and economic structures, etc - which sounds very po-faced but is actually crucial to what we are trying to do in the books.

How has your own experience shaped your interest in disability issues and other aspects of diversity?

I had two much older sisters and the oldest had a (mostly) invisible disability, in that she was an epileptic. She died when she was 19 and I was 8, and that had a huge impact on my life. Now my second-oldest sister has become multiply disabled, after a devastating stroke last year.

My sister-in-law is registered blind and uses a white stick. Her granddaughter has decided she is her guide dog, named Sapphire. So I am becoming more and more aware of these issues.

But as I get older myself, I find myself more aware of ageism - people over 60 being shown with walking sticks, grey hair, bent shoulders, when many of us are skipping about after hip replacements, unashamedly dyeing our hair and going to yoga or pilates, still working and/or looking after grandchildren. It's the big new '-ism' to my mind.

You are a parent of three children yourself. Over the years, how did you make sure you found time to read with them - and which books did they seek out?

Fortunately, my husband and myself are both avid readers and book-buyers and it helped that I also reviewed books.

We had 'family reading' as well as bedtime stories for individual daughters. I remember reading aloud the whole of The Lord of the Rings, including lots of different character voices, and the girls clamouring for 'just one more chapter'. Now the two younger daughters have children of their own and reading books is filtering down to the next generation - to my great joy.

More than ever, children need books that are exciting, surprising and stimulating. They need 'mirror' books and 'window' books: stories that reflect themselves, but also all sorts of lives they have never imagined.