Developing empathy through books

Published on: 13 March 2024

At BookTrust, we know that reading books with children helps them foster a sense of empathy towards their fellow creatures. We asked Elena Arévalo Melville to explore why this is so powerful.

Empathy is beautiful. Like gold it is precious, but unlike gold, there is an endless supply of it to be learned. It is a skill we can grow and develop.

Reading picture books to children is a two-way gift. Before children learn to read independently (and no reason why it can’t continue after) reading to them out loud is an intimate, precious moment.

You snuggle close and it’s a moment of intense shared internal/external experience. You are not only absorbing the ideas and stories meandering through the pages together, but the vibrations through the skin, and sharing the cadence of breaths, the rhythm of words. You are evoking emotional responses, suspense, surprise. Page-turning is exciting (or you dread it, depending on the book), but it is all explored in a safe space.

The shared experience of reading - commenting on what is seen, then imagining the wider world of the book together, or the consequences of actions in the book and beyond, give children a lot of tools to decode people and relationships later on. But more importantly, the time dedicated to that ritual is an unequivocal signal that your parents or carers, who are your world, have time for you as a thinker: your inner world matters. And if you have an inner world and it matters, it follows that others have their own inner world, and those other worlds invisible to us matter too.

As any book you are reading is not about you but somebody else, you get to experience characters’ struggles and successes. If you connect with them you have a practice run at being in someone else’s shoes, at seeing things from their point of view, whilst also having the distance to see it from yours from the safety of your room.

When you don’t understand why a character did something, you ask the person you are with, and the conversation that follows keeps adding to the model of the world you are building. My theory is that those books that are requested over and over again hold within them something that resonates intimately with the thinker your child is; they hold a particular key to the world model they are building.

How then do we decode the needs of others in books?

In the simplest forms, they tell us, or the narrator tells us, but there are also clues on the page, clues that are applicable to the real world.

In going through the emotions of a character who is overcoming difficulty, we actively flex that empathy muscle: we are imagining their motivations, their objectives, their feelings. Moreover, unlike real life, you can retrace and relive the experience of characters over and over again. You see others’ experiences, trials, lucky escapes, you want them to be OK, to finish the story better off.

This constant reworking of the path of wanting things to turn out OK for someone else, wanting the page turn to reveal improved circumstances, must have an effect on how a young brain develops towards a caring understanding of the world.

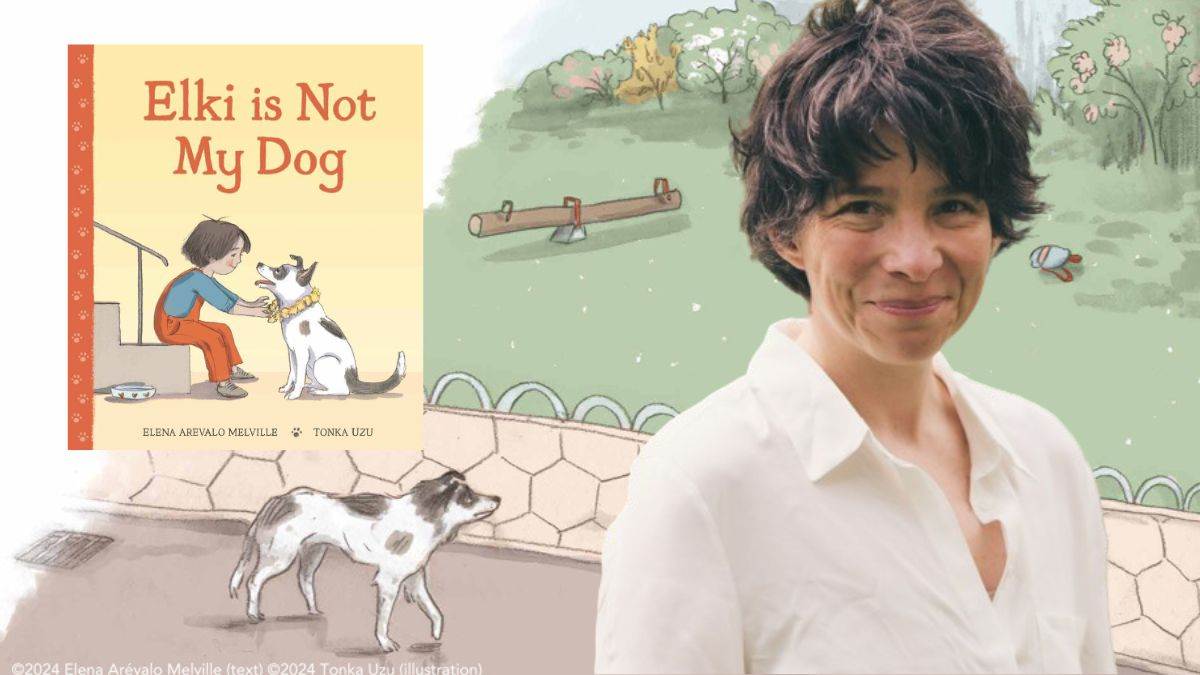

Empathy in Elki is Not My Dog

My latest picture book with Scallywag Press is Elki is Not My Dog. Stray dog Elki enters the story as a group of children are playing in the park behind their block of flats. In the first interaction a first choice is made. One of the children looks at Elki. The text begins:

Elki is not my dog. In fact, I don’t know for sure that her name is Elki.

The other friends then join in.

She must have had a name when we met her, but we couldn’t ask her because none of us speaks ‘Dog’.

Several complex issues are at play here: There is a barrier to communication when we don’t share a language; the opportunity to misinterpret or misunderstand is real, so we acknowledge what we don’t know; however, even though we don’t speak dog, we are able to infer what Elki is feeling through reading and decoding how Elki behaves.

In the story, once a child takes an interest, it ripples through their friends and later their community. Elki responds to that curiosity and kindness. The following pages show the way Elki “speaks” by different behaviours, with illustrations reinforcing the text and their friendship developing despite that lack of shared language.

Language is a true miracle. There are so many ways that we can express our feelings and aspirations and dreams with words, but something we learn from our kids is how much we can express when there is no common language. When we are interested, completely committed to understanding someone who can’t tell us what they need, as we do for our babies, we do it. For me, empathy is a committed interest in others.

In picture books a lot of the information about characters’ emotions is conveyed visually: illustrations depicting body language, eye contact, proximity, gestures, all of which we also use in real life to decode the feelings of others. Illustrators can convey this through careful observation of the real world and children can use those illustrations as safe forms for deep observation. Empathy is choosing to look, seeking to understand, and taking action.

The magic in Tonka Uzu’s illustrations for Elki is Not My Dog comes partly from deep memories from Tonka’s childhood, which were the spark for this book. There was a real dog, whose name we don’t know, and Tonka was one of those real children befriending that stray dog in Sofia, Bulgaria.

Elki is not my Dog contains a sense of collective empathy, a societal binding force that brings the community together. It is the actions of the many that bring Elki comfort, and in return she gives back to all.

The beauty of empathy shines through the community in the book. I hope that golden glow shines out of the book and into your day.

Elki is not my Dog by Elena Arévalo Melville and illustrated by Tonka Uzu is available now.

Topics: Features