The responsibility of writing stories for children about the climate crisis

Published on: 13 February 2023

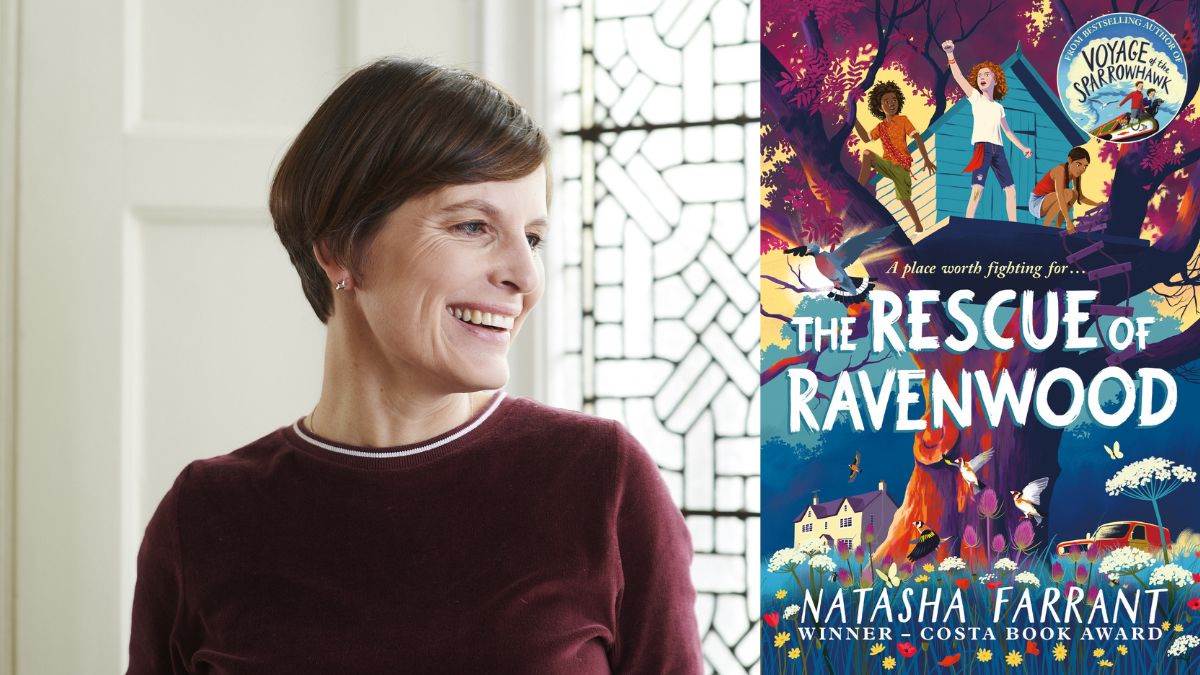

Author Natasha Farrant shares how stories affect children deeply, and how important books about the environment can be.

Picture, if you will, an eleven-year-old child, circa 1980. She is walking with her mother around a Welsh lake and she is talking – absolutely non-stop – about her favourite books. There are four children and they are sent away to a big house and there is a wardrobe and there is a witch and a lion and a faun…

The child, dear reader, was me. I can tell you absolutely nothing about the lake – I’m not even sure it was in Wales – but shall I describe to you in detail the voyage of the Dawn Treader?

Show me a cherry tree in blossom, and I am Anne Shirley, driving to Green Gables for the very first time. Put me in a rowing boat and I am George from the Famous Five, ready to battle storms. The point is, children consume books differently to adults. Now, however good the book, I am almost always a reader. As a child, I lived books, to the point where they became an active part of who I am. Medical research tells us the stories we read light the same parts of the brain as if we were to experience them in real life, and this is never more true than in childhood, when the neuroplasticity of the brain is at its highest. This is why writers for children carry a particular responsibility. The stories we read in childhood become a part of us at a cellular level.

I grew up in London, a privileged upbringing with regular access to gardens at home and wild places on holiday. Certain landscapes, returned to again and again, have become a part of me, but no more so than the landscapes I read about in books. Avonlea, Kirrin Island, Laura Ingalls Wilder’s American prairies, the Pyrenees of Belle and Sebastien.

And I was lucky. Growing up, much of the natural abundance I read about could still be found around me, even in the city. The narrow hedge behind our apartment building was alive with bluetits, sparrows pecked at milk bottle tops on frosty mornings, butterflies returned en masse in the summer and everywhere I walked in the countryside rabbits scurried before me. All so common I barely noticed them, all heart-breaking rarities now.

More and more, this loss is the only story I want to tell. The challenge of how to safeguard our natural world underpins so many aspects of my life, and writing about it is my way of taking action. The question is, how to write about the climate and environmental crisis for young people? Keeping in mind that particular responsibility a children’s writer has towards their readers, how to steer a path which is both hopeful and true?

I wish children everywhere could grow up free of care, untroubled by war and want and climate chaos. But we are where we are, and children are not fools. They know about the climate crisis – they’ve been hearing about it since the day they were born. It makes me so angry when I hear people say that the next generation will save us. Firstly, there isn’t time for that. And secondly – why should they? They didn’t make this mess. Plus, they’re children. How can we heap responsibility on their shoulders for saving the entire world? Rather than pretend they can solve a whole crisis, perhaps the most useful thing to do, with my writing, is to give them a toolkit, as it were, for navigating an imperfect world.

In The Rescue of Ravenwood, it’s not the whole planet that needs to be rescued but one place – a house, a wood, a garden, a solace for wildlife and for people. It’s an adventure about three children who will stop at nothing to save it, and who in the process take control of their own future. As I wrote, it occurred to me that perhaps talking to children about the climate crisis is simpler than we think. Perhaps, rather than give in to despair, what we need is a call to arms for each of us to do what we can. It’s a thought best summed up by one of the main characters, Bea, in conversation with a fellow passenger on a train.

“We have to fight for the precious places, don’t we?” Bea says. “It might not change the world for everyone, but it’s a start, isn’t it?”

To which her interlocutor replies, “It is a very good start indeed.”

To quote Neil Gaiman, paraphrasing Chesterton:

“Fairy tales are more than true — not because they tell us dragons exist, but because they tell us dragons can be beaten.”

If you can imagine something, you’re already on the path of making it happen. And if writing is a form of activism, this is never more true than when writing for children. Writing for children is an act of hope, of belief in the next generation. I want to offer my readers a vision of the world as it could be – a world of life and abundance, in which children band together to fight and win, in which their actions make a difference. I want that vision to sink into their bones.

To conclude where I started, by that lake which may have been in Wales. A few years ago, roadworks led me on an unexpected drive across Exmoor. At one point, we reached the top of a hill and there beneath us between two hills lay a body of shimmering water. I recognised it at once. Cair Paravel, I breathed, and you know what? I wasn’t wrong. A few minutes later, we came to a village. Warleggan, its entrance sign proclaimed. Twinned with Narnia.

In that moment, in my heart and possibly against all rational judgement, I knew that all would be well with the world. For hadn’t I learned it long ago, in books?

Natasha Farrant is the author of The Rescue of Ravenwood.

Topics: Environment, Features