The importance of exploring grief in children's books

Published on: 05 December 2023

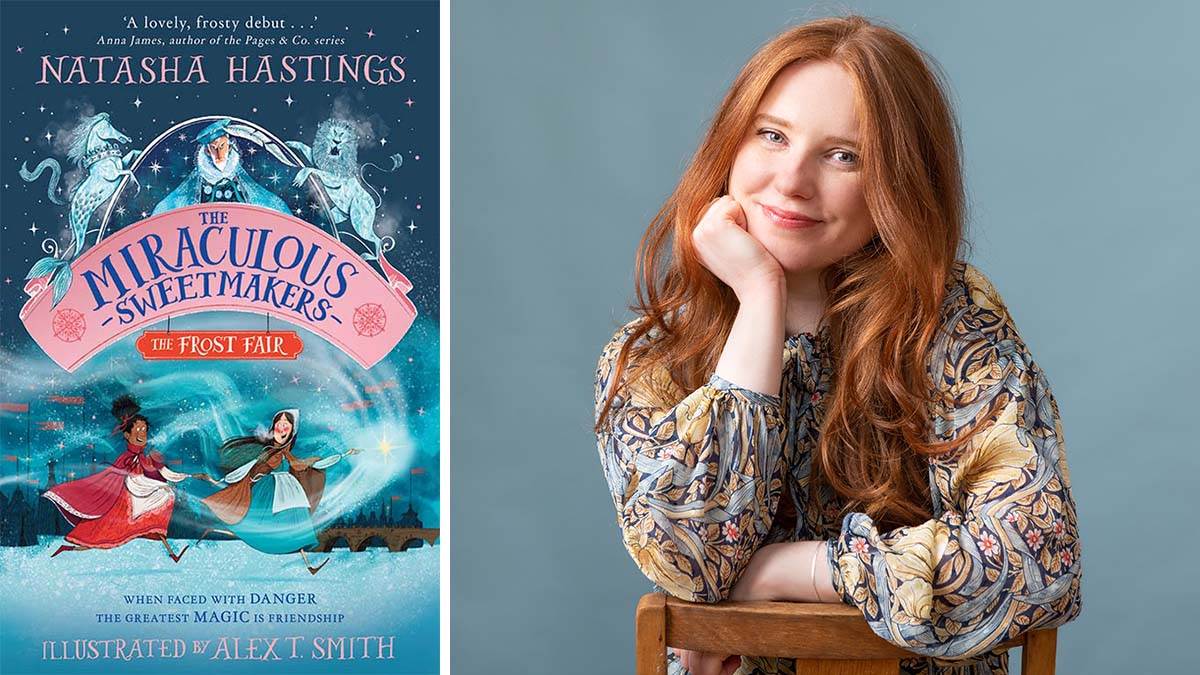

At BookTrust, we know that reading books about difficult subjects can be a way for children to stimulate empathy and to explore emotions. We asked author Natasha Hastings to explore why this can be so powerful.

Photo: Claire Connold

When I was in primary school, someone I was very close to died unexpectedly.

I folded the hurt up in my chest, packing it away as carefully as I used to fold my pyjamas under my pillow. It didn't occur to me to talk about it to any of my classmates or teachers. It didn't feel safe to. Nor did it feel like I could talk about it at home, where my sadness was one hurt in a sea of so many others.

When I first found out about the death, I gave an involuntary giggle. I giggled. For years I thought that made me a spectacularly evil person. Why else would I, finding out some desperately sad news, laugh? It was only much later, while reading a book, that I realised this is a very common nervous reaction. I can't remember what story it was, but I remember staring at the page in shock after seeing a character do the same as I had. It felt as if I'd just been given a soft, warm hug.

How books equip children with emotional tools

I always internally raise an eyebrow whenever someone questions whether it is appropriate for children to read about death and grief in fiction. For children who haven't been bereaved, books give them the means to rehearse feelings before experiencing them, and to empathise with those around them. Sad, unexpected things happen in life, and we can't protect children either from experiencing such things themselves, or else hearing about it from classmates, teachers, friends or family.

Isn't it a good thing to equip children with the emotional tools they need, so they can learn to be kind to themselves and others in a safe context – or do adults expect children to suddenly become emotionally mature upon turning 18?

And what about children who have been bereaved? Are they not palatable enough to be represented in the books they read? Children aren't given a roadmap to cope with grief: they are experiencing everything for the first time. Some children are blessed with emotionally mature caregivers, while others aren't.

I believe it is our duty to equip them with as many resources as possible to navigate one of life's most hurtful paths. After all, pain doesn't pass if we ignore it. It stays until it is managed, often very inconveniently showing up to remind us we haven't dealt with it yet.

Exploring grief in The Miraculous Sweetmakers

In my novel, The Miraculous Sweetmakers and The Frost Fair, grief is blended into the everyday, manifesting itself differently in characters. Thomasina's father becomes a hoarder of his son's belongings. Thomasina's mother takes to her bed and has a very limited engagement with the outside world. And Thomasina has an impossible wish: to bring her brother back from the dead. She blames herself ruthlessly for his passing, speaking to him in her head.

But there is also joy to be found in these pages, where characters seize happiness by selling sweets on the frozen River Thames, or visiting a magical Other Frost Fair, or riding on an enchanted Frost Bear through the woods on a secret mission.

I want to show children that emotions are nothing to be worried about. It is the suppression of them that leads to deep pain. We can best manage them by channelling them into a helpful context.

In my book, Thomasina gets to be angry. Properly angry: at herself, her family and the world. She gets to be loud, and quiet, and tearful, and anxious, and crave reassurance, and she is shy, and confident, and brave, and full of joy. She is an entire, flawed person, and loved because of it. I celebrate her rage, passion and anguish because it makes her vibrant, and feeling, and alive. It helps her heal.

In the penultimate chapter of The Frost Fair, there is an emotional resolution to the tale. Thomasina witnesses her most painful memory – that of her brother's passing. She learns to forgive herself for being a flawed, imperfect human being, in a way I had to forgive myself to write The Frost Fair in the first place. In reading The Frost Fair, whether as a child or an adult, I hope the reader realises we are worthy of love, despite our flaws. That the people who passed always knew this anyway, with a wisdom only the dead can ever have, and loved us because of and not despite our failures.

The impact of stories on children

As an author, you always hope that your book will find someone who might truly need it – but nothing prepares you for when this happens.

While signing books at a primary school recently, a child came up to me and explained that, just like I'd mentioned in the assembly I'd given, someone close to them had recently died, too. I won't tell you the rest of our conversation, because such things are sacred between the author and her readers. What I will say is that when our conversation ended, I was left wondering if what I'd said to try and offer some comfort had been enough in that moment.

But I knew the child had a copy of The Frost Fair. As we packed up my books, walked to a car, and I teared up on the way home, comforted by a very lovely Waterstones bookseller and my publicist, I knew that if I could make even just one person in the world feel less alone, then I'd done my job as an author. That the pain I'd gone through as a child could end up being someone else's soft, warm hug.

The Miraculous Sweetmakers and The Frost Fair by Natasha Hastings is out now.

Topics: Bereavement, Features