Boys do cry: How books could help young boys to express their emotions

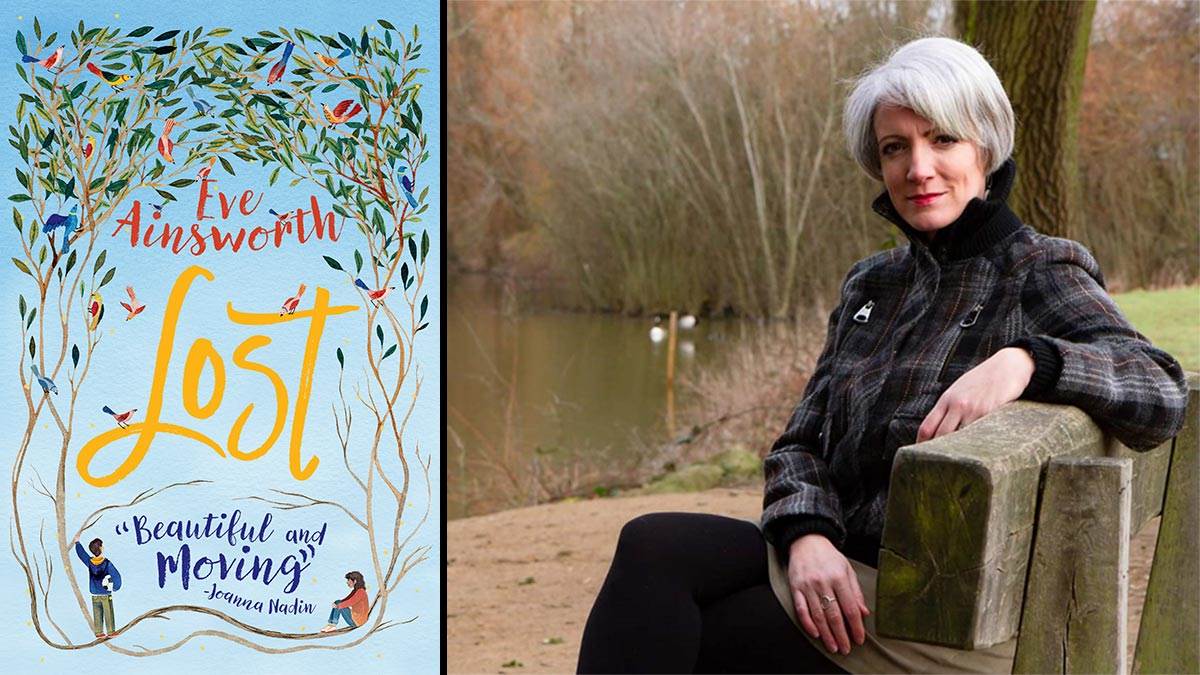

Published on: 17 July 2019 Author: Eve Ainsworth

Eve Ainsworth's new story Lost is a moving tale about a child struggling to cope with the death of his mother. Eve tells us why it's so important that we help young boys to express their emotions...

My 8-year-old son often talks about his worst day at school. It happened when he was six and his best friend laughed at him for being upset about his Grandad dying. The 'friend' said that he hoped his other grandad would 'die too'.

'He called me a baby,' my son said to me in the car, later that day. 'He told me I was a baby for crying.'

I told him that he wasn't a baby; that crying was a normal and healthy reaction to sadness. I read him books like Badger's Parting Gifts by Susan Varley, Granpa by John Burningham and, later, A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness to help untangle some of the fears and feelings that he was struggling to articulate.

Granpa by John Burningham

Fast-forward two years and my son had moved school and was telling his new classmates about the day when he felt sad. He explained how awful it had it been to lose his beloved grandad, but also how horrible it had been being teased for being upset.

It made him question whether he should have kept his feelings to himself. He said that crying had made him feel weak and now he would try to avoid being upset in front of others again.

At only eight, my son was articulating what so many boys of his age and older struggle with – the suppression of emotions.

Seeing crying as a crime

Illustration: Emily Rowland

This was reflected in the work I was doing with a large secondary school in a pastoral support role. I'd seen so many boys lock away their feelings or allow them to escape in more 'acceptable', masculine ways - in other words, in rage or anger.

It was seen as a crime for a boy to cry at this secondary school, as if it was a sign of weakness or failure - even if that would have been the best thing for him to do.

One boy in particular sticks in my mind - a young Year 7 boy who had lost his mum to cancer. I'll never forget how closed-up this student was. He would come to my office and simply sit, slumped at my desk. If I tried to talk to him, he would lie his head down and close his eyes.

A relative told me that his dad was the same. Both of them were refusing to express their feelings for fear of what might come out. Ultimately, both were terrified of unleashing their grief, as if it were some kind of unruly beast that needed to be kept restrained.

It was only through the dedicated work of the charity Winston's Wish that this boy and his father were slowly able to unpick their emotions and allow themselves to properly grieve. And only after this process could the healing begin.

Helping boys to articulate their emotions

Illustration: Erika Meza

This was not an isolated incident. I worked with many challenging and angry young boys. Boys who would shout and kick. Boys who would ram their fists against the walls and slam out of classrooms, hurling a string of abuse at those left behind them.

Ultimately, these were all young men linked by the same thing - they were all struggling with big issues in their lives and unable to articulate how this affected them. Whereas the girls in similar situations would often sit down and express their fears and worries, the boys rarely could.

I worked with boys who were in secondary school and it was much harder, at this age, to knock down the walls that they had begun to construct tightly around themselves.

It's essential therefore to have discussions and interventions targeted at younger children - ideally upper primary, before the pressures of secondary school kick in and before these self-constructed walls are built too high.

This was why I wanted to write Lost, a book about a boy dealing with grief, and why I wanted to target a younger, middle-grade audience.

The difference that books can make

In Lost, Alfie is really struggling to channel his feelings. He thinks that it's wrong to cry. He believes he should be 'strong' for his dad. I wanted to show in this book that true strength comes from accepting the pain and talking about it.

As an author and an avid reader, I am always going to advocate that books can help. But the simple truth is: they can. Books can lessen isolation, bridge the gaps between understanding and help to encourage the need to talk and share our feelings and experiences.

Because that's what we need to do above all else: talk.

We need to be open about the challenges that face us in life, and, more so than ever today, we need to ensure that boys are able to grieve properly. We need to promote the message that crying is not just okay, but is a necessity, for boys as much as anyone else.

How books can help children explore grief

Topics: Bereavement, Bullying, Personal/social issues, Features, Feelings

Add a comment