How books build empathy and help children see other points of view

Published on: 10 April 2019 Author: Candy Gourlay

Candy Gourlay has just been shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal. She feels this is a message to Filipino children – and children of other backgrounds – that their stories too belong on the pages of a book. Here are the many reasons why that is so important...

Hello, dear readers, your BookTrust Writer in Residence (that’s me!) has just returned from a bit of world traipsing – including a book tour of England that started in Telford and ended in Brighton…

At the beginning of my book tour at Telford Priory School in Shropshire

At the beginning of my book tour at Telford Priory School in Shropshire

Then to Hong Kong for the Young Readers Festival, where I visited two to three schools a day over the space of a week.

Bringing my magic fish bag to Shrewsbury International School in Hong Kong! Photo: Mio Debnam

Bringing my magic fish bag to Shrewsbury International School in Hong Kong! Photo: Mio Debnam

Then over to the Philippines, where I visited more schools and launched the Filipino editions of Is It a Mermaid? and Bone Talk.

Visiting Raya School in Manila. Photo: Allyana Liesel Lopez

Visiting Raya School in Manila. Photo: Allyana Liesel Lopez

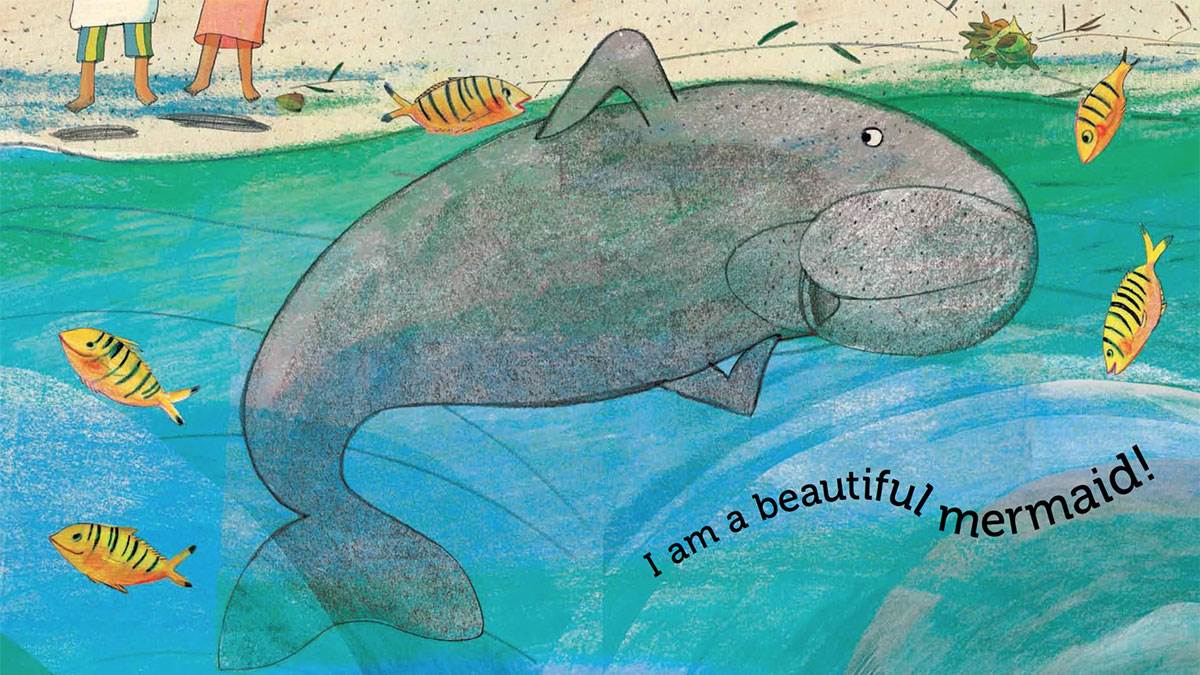

Everywhere, I have been reading aloud from my picture book Is It a Mermaid? (beautifully illustrated by Francesca Chessa). It’s about a tubby, delusional sea cow who thinks she’s a mermaid.

‘I am a beautiful mermaid!’ Illustration: Francesca Chessa

My mermaid sea cow is a cousin of the manatee – the dugong. Just saying the word ‘dugong’ (DOO-gohng) makes everyone laugh – laughter that becomes more boisterous as the dugong’s claims to being a mermaid become more extreme. 'SHE’S NOT A MERMAID!' the children shout.

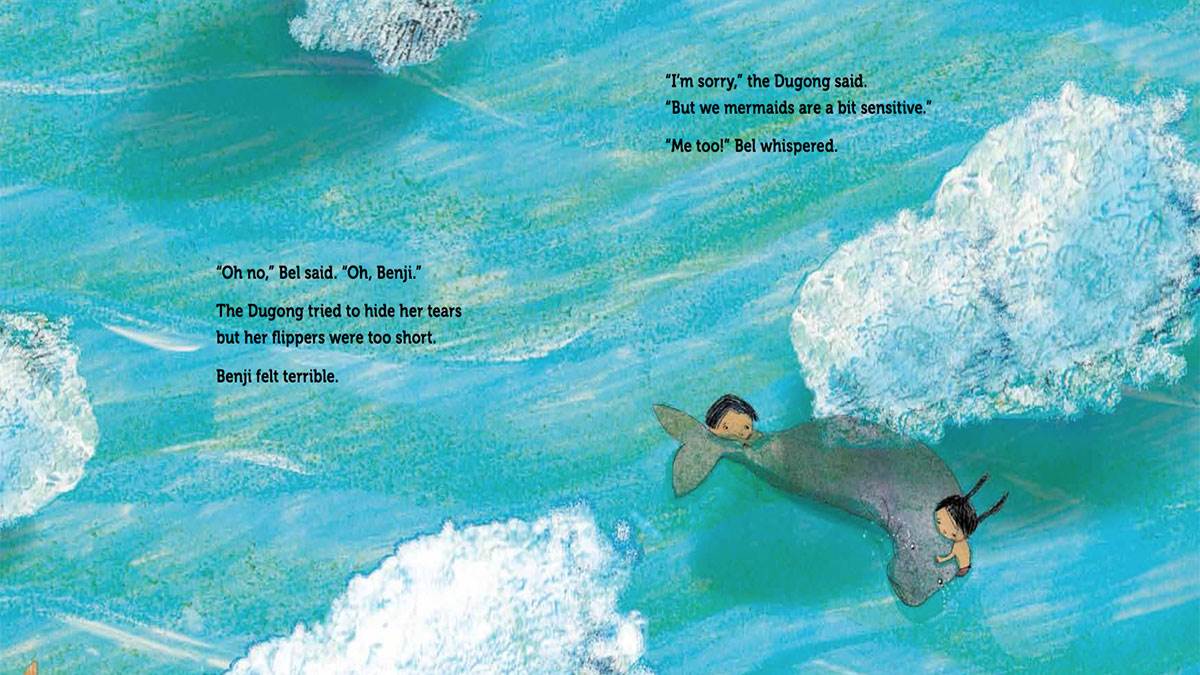

And then we come to this page…

‘The dugong tried to hide her tears but her flippers were too short.’ Illustration: Francesca Chessa

Suddenly, the room becomes silent. I can hear a pin drop. Gazing at all the solemn, upturned faces around me, I can see that the children are just as upset as my story dugong.

At that moment, there is a shift. The children had been laughing at the dugong. But now they find themselves inside the dugong’s skin. And they can feel her hurt.

That’s the power of stories. What may seem "other" in a story can be the path that leads back to you, the reader.

More about our Writer in Residence, Candy Gourlay

My auntie is Filipino

In Hong Kong, I visited many schools with beautiful libraries, most populated by Chinese children – both from Hong Kong and mainland China.

When I am presenting Is It a Mermaid?, I always begin by reading out the illustrator Francesca Chessa’s name. 'Where do you think Francesca is from?' I ask the children.

'France!' is always the first guess. Eventually (with the help of a few prompts like '"Chessa" rhymes with pizza and pasta'), the children figure out that Francesca is Italian.

Then I ask them where they think I’m from. The first guess is always ‘Hong Kong!’ And then the guesses go all over the place. Canada? The United States? Australia? Thailand? Indonesia? Sometimes the children never figure it out and I have to volunteer that I am from the Philippines.

Immediately, there is a murmur of recognition. 'The Philippines?' the children exclaim, one by one. 'My auntie is Filipino!'

In Hong Kong, the children call their Filipino nannies and babysitters "aunties". Almost half the domestic workers in Hong Kong are Filipinos.

From the corner of my eye, I see the teachers wince at the children’s declarations. They are worried that I might be offended. But the truth is, I am pleased that the children have made the connection between me and their nannies.

In an earlier career as a journalist, I had done much reporting about the migration phenomenon in my country (about 11 per cent of our population goes abroad to seek work, and Hong Kong is only an hour’s flight away). I have written about the exploitation and abuse many overseas Filipinos face, about their invisibility in the societies they are transplanted to.

Realising that Filipinos can be authors too, I hope, will disrupt any fixed perceptions these children may have about us: perhaps it will make them question their assumptions, be more curious about their aunties… in the same way a good book can disrupt a reader’s perceptions of the world she lives in, revealing a vast, unknown space that needs to be explored.

Need to humanise

For so long, children’s literature has represented a certain default – white, middle class, cis, able-bodied – and readers and book buyers who are accustomed to being represented in stories may not consider themselves the audience for diverse books. Aren’t books with brown faces only for readers with brown faces?

India-born author Chitra Soundar (You’re Safe With Me) says: 'I write mainly stories that touch upon India in some way… These stories are definitely for the Indians who live everywhere in the world… but is that all? Surely these stories appeal to everyone else?'

Oh but their need to see people unlike themselves is just as great... in the same way that my audiences in Hong Kong awakened to the diverse humanity of Filipinos.

Walter Dean Myers (winner of the Michael Prinze Award in 2000 for his novel Monster) quotes a lawyer defending poor clients: 'The trouble is to humanize my clients in the eyes of a jury. To make them think of this defendant as a human being and not just one of "them".'

Writes Myers: 'I realized that this was exactly what I wanted to do when I wrote about poor inner-city children – to make them human in the eyes of readers and, especially, in their own eyes.'

Rudine Sims Bishop – we all quote from her critical work Mirrors, Windows and Sliding Doors (PDF), which originally appeared in Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom in 1990 – says it is important to remember that diversity 'needs to go both ways'.

Windows and mirrors

In a video interview, Bishops says: 'It’s not just children who have been under-represented and marginalised who need these books, it’s also the children who always find mirrors and therefore get an exaggerated sense of their self worth and a false sense of what the world is like.'

'As much as kids need books to be mirrors, Kids also need books to be windows,' Grace Lin, the award-winning Chinese American author, says in a 2016 Tedx Talk.

'Kids who always see themselves in books need to be able to see things from other viewpoints. How can we expect kids to get along with others in this world, to empathise and to share, if they never see outside of themselves?'

Books as windows, she says, is the path to self-worth and empathy.

Living in the United Kingdom, it feels like such a luxury to discuss representation. Growing up in the Philippines at a time when most books were imported from the United States and the United Kingdom, Filipinos did not really exist on the page.

Absence used to be my normal and all the stories I wrote as a young person featured white heroes, living in snowy, Western settings totally alien to my tropical landscape. Though I wanted to become a children’s author, it was years before I gave myself permission to make my dream come true.

Last month, I returned to the Philippines – happily now host to a vibrant publishing scene – to launch the Philippine editions of Bone Talk (Anvil Publishing) and Sirena Ba Yan?/Is It a Mermaid? (Adarna House).

Imagine my joy when it was announced that Bone Talk had been shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal.

A screenshot of my Instagram story celebrating Carnegie shortlisting at the Manila launch of Bone Talk

For someone like me who had spent all my life searching for people like myself in the pages of books, the shortlisting is more than a personal honour.

It is a message to Filipino children – and children of other backgrounds – that their stories too belong on the pages of a book.

Add a comment