'An army carrying pencils and notebooks': Telling the story of Cuba's brigadistas

Published on: 12 July 2018 Author: Katherine Paterson

Bridge to Terabithia author Katherine Paterson didn't think she would write another novel. But then she found out about Cuba's literacy campaign and couldn't help but tell the story in My Brigadista Year...

Five years ago, I thought my career as a writer of fiction was over. It wasn't a tragedy if I never wrote another novel. I was past 80, and I'd had a good run. I have never been one of those writers who think if they can't write they might just as well lie down and die. I might want to lie down and die if I couldn't read. But nothing was keeping me from the many books I wanted to read before I died.

And then I got an email from my friend Emilia Gallego in Cuba. She was once again inviting me to her conference in Havana for Latin American literacy advocates.

Before the trip, I ran into my friend Mary Leahy, the sister of Vermont's Senator Patrick Leahy. 'I'm going to Cuba and I was hoping I could get your brother to write a letter for me to read to the participants,' I told her. 'He is such a hero to my friends there.'

'I'm so jealous,' Mary said. 'Pat gets to go to Cuba all the time, but I've never been there. When I began working with adult literacy in Vermont, I took ideas for our work from the great Cuban literacy campaign of 1961.'

'I never heard of it,' I said.

Becoming a literate nation

In the fall of 1960, Castro addressed the United Nations and declared that in one year, Cuba would become a literate nation. He believed that in order to build a strong nation, you had to have a literate citizenry.

Back in Cuba, he put out a call for volunteers. If you can read and write, he said, you should teach someone else how. He got some 750,000 volunteers, and about 108,000 were between the ages of 12 and 18.

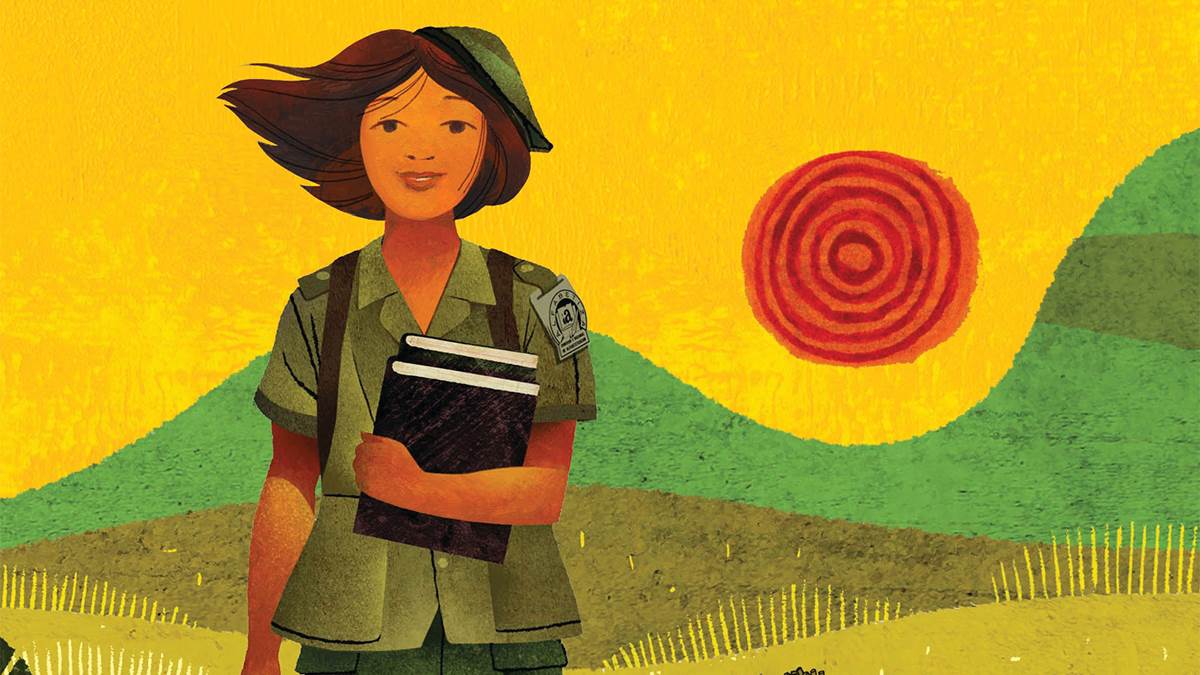

The young volunteers were called 'brigadistas' because they formed a uniformed army brigade, but one carrying pencils and notebooks instead of weapons of war.

Young girls left their sheltered homes and protective parents and went up into the mountains to work beside the campesinos in the daytime and, at night, teach them how to read and write.

After the campaign ended, the United Nations observers declared Cuba a fully literate nation. Today Cuba's literacy rate is one of the highest in the world, being anywhere from 99.7 to 99.9%.

Telling the story

I now knew what I wanted to say in my speech at Emilia's literacy conference for her Latin American colleagues. I emailed my talk to Isabel Serrano, who was to translate it into Spanish. In her return email she said: 'You knew Emilia was a brigadista, didn't you?'

When I got back from the conference, a friend said: 'You should write that story.'

Should I really? I got in touch with Karen Lotz. I have known Karen since she was a young assistant at Dutton books. She might not think an 83-year-old American would be crazy to write about something that happened in Cuba in 1961! I was thinking of a non-fiction book with lots of pictures, but Karen said: 'I can hear the excitement in your voice. I think it should be a novel.'

So I decided to tell this story that few of us in the United States have heard and no one, that I knew of, was writing about in a book for the young.

Under Castro's leadership Cuba became a fully literate nation, a country where education is free from cradle to grave - in other words, from pre-school through to doctoral degree - and every Cuban has access to excellent medical care.

Some might say the history of the U. S government's actions against Cuba and much of Latin America hardly gives us the right to judge what we perceive to be their injustices. As Lora says in the epilogue to her story: 'My country is not perfect, but, then, is yours?'

My Brigadista Year is out now, published by Walker Books.

Topics: Coming-of-age, Around the world, Features

Add a comment