Celebrating accent and dialect – the importance of poetry to reflect children’s identities

Published on: 05 October 2023

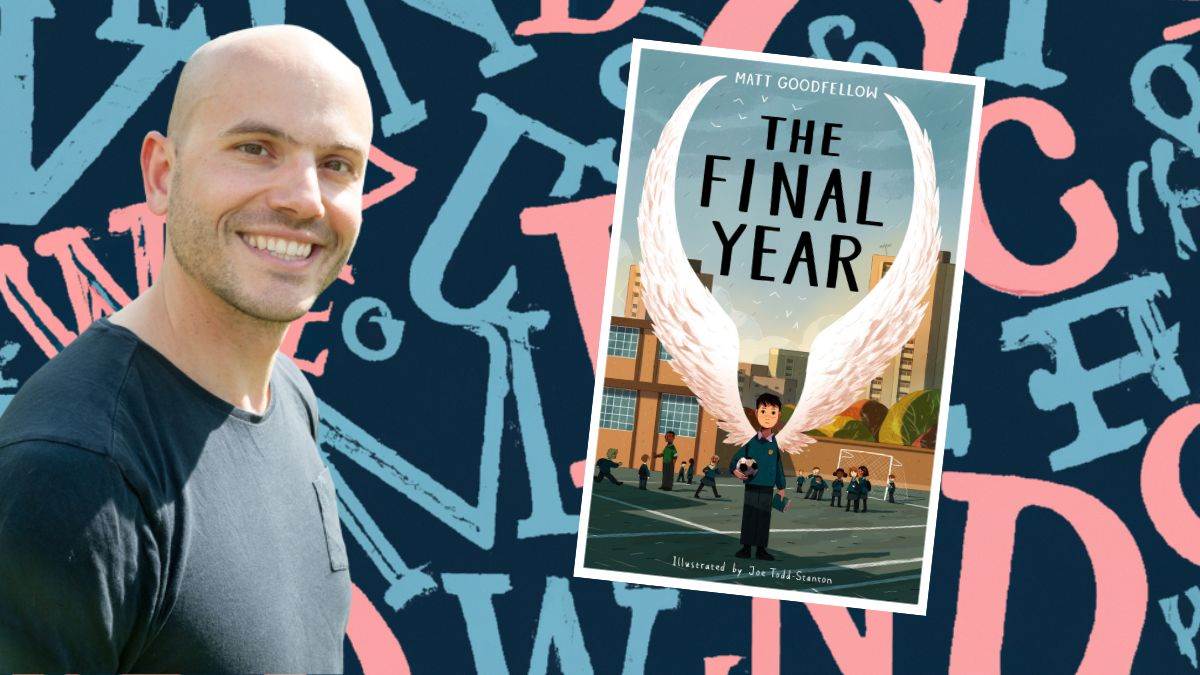

Poet Matt Goodfellow explains the importance of children reading and writing in their own voices.

The main character in my new verse novel, The Final Year, is a boy called Nate who is moving from Y5 into Y6. Nate is from a background where there is lots of love and lots of chaos to navigate. He’s the oldest of three brothers and he has to take responsibility for caring for his brothers when Mum’s not around. As he moves into Y6, Nate’s teacher, Mr Joshua, recognises that he has a spark within him that can be explored and expressed through the poems that Nate writes. Nate also has to contend with trying to control his anger, The Beast. When I was writing this story, I immediately knew that Nate had to express himself in his own Manchester accent and dialect. I did this because I wanted his voice to be authentic – I wanted him to be proud of his identity and his cultural heritage. I was also able through Mr Joshua to vocalise some of my thoughts on the current education system and the intense pressure put upon teachers and children to pass SATS tests etc.

When I work in schools as a poet, it’s my job to show teachers and children that their voice matters – and that their experiences of life up to that point are valid. And should they choose to, they can use poetry as a way of expressing their own thoughts and feelings and ideas. We look at how poets can push language around and change spellings of words to replicate their own accent – and how they can write poems with the words they have in their head already. Why? Because I believe this voice has a power.

I was a primary school teacher for 10 years, working in East Manchester. Most of my teaching career was spent as a Y6 teacher – Nate’s Y6 classroom in The Final Year is my classroom. I believe that poetry is the only space in the current curriculum where teachers can facilitate creativity through writing in a totally different way – far from the constraints of age-related expectations. But just as importantly, I believe, is to give both teachers and children the message that standard spoken English is an outdated concept that doesn’t serve any purpose in this beautiful, modern cultural melting pot of a country. The voice that a person grows up with, the words and phrases that show who they are and where they’re from are incredibly important – it forms part of your identity. I wholeheartedly oppose the idea that teachers and children aren’t allowed to use their own voice simply due to the ideas of a group of powerful people a hundred and fifty years or so ago who decided that the way they spoke English was the only way to speak English – and if your accent and dialect differed from this, you were somehow to be thought of as inferior or uneducated.

The children I taught were bright, sparky and often street-wise kids that used their natural northern dialect to express themselves. Now, like every other teacher in the country, I was under pressure from Ofsted and therefore my HT and SLT to model and expect the use of standard spoken English in the classroom. The children I taught would ask: ‘Mr Goodfellow, can I go toilet?’ or in answer to a question about what they’d done over the weekend, a typical response might be: ‘I went town with me dad.’ I, of course, had to say: “I think you mean ‘Can I go to the toilet?’” and “I think you mean: ‘I went to town with my dad.’”

Early on in my first year as a teacher, a lad in my class asked me a question which stopped me in my tracks: “Mr Goodfellow, how come you tell me it’s wrong to say ‘Can I go toilet?’ when my dad says it, and my grandad says it?” And I got what he meant immediately. The way we talk, our accent and dialect, is part of our cultural heritage, full of the musicality and nuance of our history and experience of life.

Explore the work of poets like Val Bloom, John Agard, Grace Nichols and Benjamin Zephaniah and discuss how poets can push language around like playdough to change the spelling of words so the reader is forced to speak in the poet’s own accent and dialect. It’s incredibly empowering for children to explore, in Zephaniah’s beautiful poem ‘I Luv Me Mudder’, why he chooses to write:

I luv me mudder an me mudder luvs me

We cum so far from over de sea

in the way he does.

I believe he writes it like this because he’s proud of his voice and accent, and proud of his cultural heritage.

When I’m working in schools across the UK, I encourage children and young people to write in the voice they think in, the voice they use with their mates and parents. Because this is their real voice – and as I said earlier, it has a power.

I think it’s important for children, young people and adults to understand that nobody owns language – and poetry is a space for rebels to express themselves however they choose – far from the constraints of standard spoken English.

Let the children and young people discuss the way they speak outside of school and gather together words and phrases that show who they are and where they’re from. Celebrate this.

After The Final Year was published, I was lucky enough to work with two professors of linguistics from Manchester Metropolitan University, Rob Drummond and Ian Cushing. Ian in particular has written numerous papers about how the notion of standard spoken English is completely outdated. I agree.

Let poets and poetry into classrooms – let accent and dialect be celebrated – and let the many beautiful voices of communities be put at the centre of the curriculum.

Across the course of The Final Year – Nate explores his voice, explores his grief, his sadness, his anger and bewilderment in his own voice. The voice of power.

The Final Year by Matt Goodfellow and illustrated by Joe Todd-Stanton is out now.

Topics: Poetry/rhyme, Features