'I sometimes wished I could be one thing properly': Michael Mann on growing up half-Indian, half-Yorkshire and the beauty of the "in-between"

Published on: 14 October 2021 Author: Michael Mann

Michael Mann reveals how his mixed heritage inspired his magical adventure book, Ghostcloud, as did other elements in his life, such as being a primary school teacher and an early family loss.

My first book, Ghostcloud, follows 12-year-old Luke Smith-Sharma, who shovels coal in a power station, deep underground. Miserable, he dreams of returning home, but when the chance arises, it is from an unlikely source: a ghost-girl called Alma. Alma tells him that there is a secret way out, but more importantly, that Luke is a rare being – half-human and half something else. As they try to escape, they’re drawn into a whirlwind adventure through the skies and furnaces of a reimagined London, where nothing is quite what it seems.

The story is ‘wildly imaginative’ (according to Waterstones!), but many of the big ideas have very real roots, linked to my heritage, family and teaching experience. In this article, I go through a few that matter most.

Mixed heritage and the in-between

I’m half-Indian and I moved to Yorkshire at ten. When I was younger, I often found myself apologising for my "half-ness": 'Sorry, I know, I go pretty white in winter' or 'Yeah, I sound southern, but I say "bath" not "baaarth". It wasn’t awful. Most people were nice about it. But sometimes I wished I could be one thing properly.

Even the books I loved – from Roald Dahl and Tintin to the Indian myths my mum gave me – never featured half-people like me. I didn’t complain. I decided I was the exception rather than the rule.

But then I became a teacher and I saw that I was wrong.

So many of the kids I taught were "in-between" in some way. They might identify as South American, but not speak a word of Spanish. Or they might speak Turkish, but identify as Bulgarian. Or be a girl who liked football, or a boy who didn’t. Most kids, at times, feel they don’t quite fit the categories.

And gradually, in Ghostcloud, that "in-between" became a theme. Luke is half-Indian too, but trapped underground, he’s so pale that nobody believes him. His friend Jess wants to be a plumber, even though the guild doesn’t allow girls. And Alma, the ghost-girl, isn’t sure she ever wants to reach ‘the other side’. The three start off apologetic – protesting too much – but in time, they see all these things might be a strength. That they’re not lacking, but whole.

My grandad, the sky and shades of grey

When I was seven years old, my grandad died. His name was Luke and he was a coalminer.

I distinctly remember looking for him in the sky, wondering if he was watching me from heaven. Wondering if when I saw a shape in the clouds, it was him, somehow, watching me back.

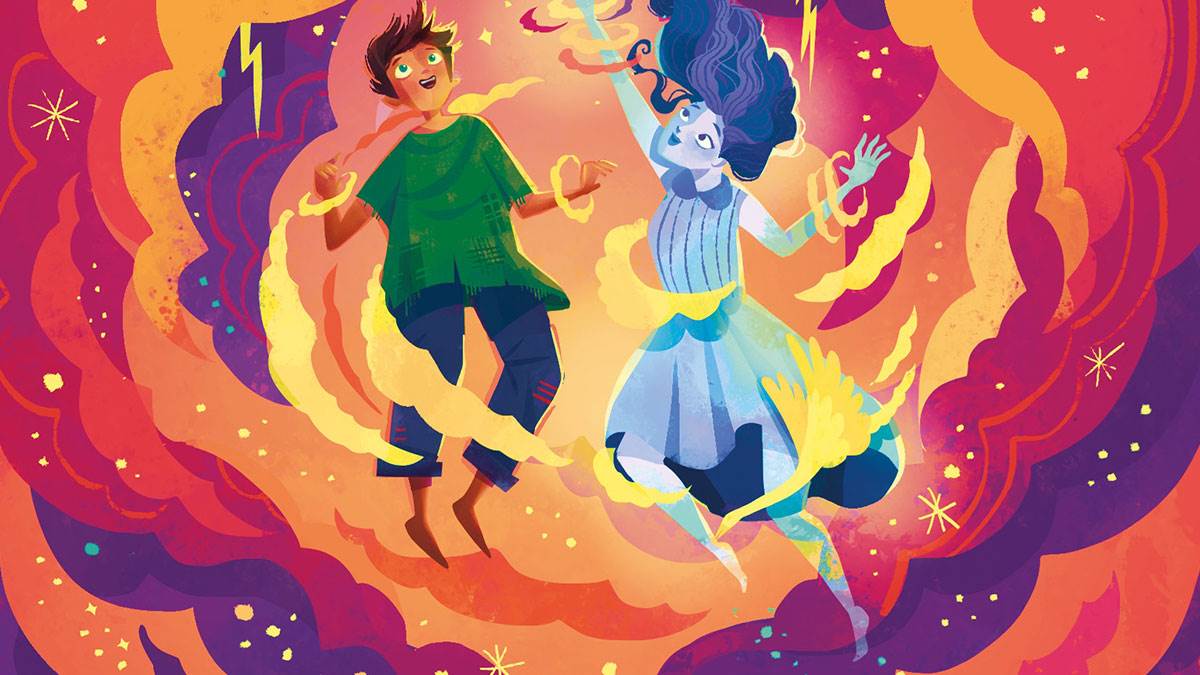

Illustration by Chaaya Prabhat, from the front cover of Ghostcloud by Michael Mann

Illustration by Chaaya Prabhat, from the front cover of Ghostcloud by Michael Mann

This feeling developed into one of the book’s big ideas – that of a ‘ghostcloud’ world, right above our heads, where the shapes in the clouds are not quite what they seem. Luke visits this world and learns to do the things these ghosts can: to ride the clouds, bend their shape to his will, fire lightning and make it rain. He also begins to question things. Clouds don’t try to fit in - they’re constantly changing, growing, merging. They’re rarely black and white, more shades of grey. And Luke starts to wonder if he could see things more like they do.

My students and the importance of turning the page

As a teacher, I see too many kids give up on books. Sometimes I see the exact moment they switch off at story time – usually when the description goes on, or the plot gets boring. Each time this happens, it breaks my heart.

At some point, I made a decision. There was no point writing beautiful stories – with diverse heroes and big ideas– if the child puts the book down. First and foremost, you must keep them turning the page. So when I wrote Ghostcloud, I crammed it full of peril, cliffhangers and dastardly villains, plucky heroes and daring escapes, so that children have no choice but to keep reading right to the end.

The end is crucial – that’s when we see the hero triumph, despite their background. And if they reach it, then the reader will know that they can do the same.

Topics: Family, Diversity (BAME), Features