The Perfect Shelter: Talking to children about serious illness

Published on: 19 July 2021

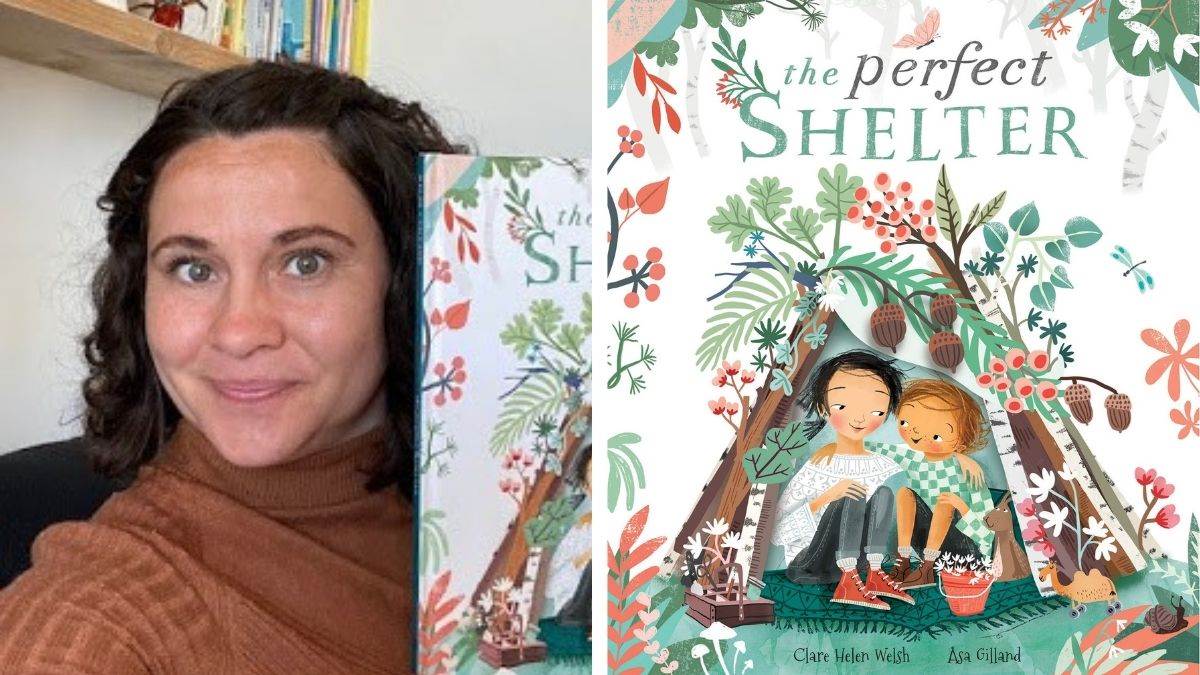

When author Clare Helen Welsh was diagnosed with cancer, she knew one of the hardest things she would have to do would be to tell her children. She shares what she learned from the experience and why she wrote The Perfect Shelter, as well as tips for families who might be going through something similar.

Telling my children that I had cancer is one of the toughest things I have ever had to do. My daughter squeezed me so tight that even now the memory brings tears to my eyes.

How to talk to children about serious illnesses almost definitely depends on the age of the child, the child’s personality, and the nature of the illness you face, as well as how you yourself are managing. However, I’ve put together some of the things that helped us at an especially difficult time, in the hope that they can offer support and ideas to others if they are needed.

When

I decided to break the news when we knew exactly what we were facing – when we had a clear idea of the type of cancer and crucially, the prognosis. I wanted to be honest and confident, but I could only do that once I had gotten my own head around everything. I did pre-empt things, explaining to my children, who were 9 and 10 years old at the time, that I was having tests for a lump.

I chose a ‘good day’ when I was feeling more on top of things. There were plenty of times when I really struggled with the uncertainty, but speaking when I was more in control of my feelings meant I could do so calmly and coherently. It’s a hard balance to strike though.

Whilst I wanted to appear strong, I also knew that if my children saw me struggle, then they would have permission to struggle too. So, whilst I held back the tears initially, I didn’t hide the hard times from them completely.

Where

As well as picking a moment when I felt as relaxed as possible, I also choose a place I felt comfortable, somewhere we all felt safe. For us, that was in our kitchen around the dining table, where we could cry, be angry, or express our feelings in any way that felt appropriate at the time.

How

Well, this is the big one, isn’t it – how do you deliver devastating news to your child? I’m pretty sure it went along the lines of - ‘You know that lump the hospital found… the results are back, and they’ve told us that it’s cancer.’ I then chatted about the size of the tumour, where it was and other details about treatment going forwards, giving the children time to process it all. We talked as a family about whether to use the C word or not, and ultimately decided that not naming the tumour as cancerous would have made the word feel even scarier. Using the word from day dot helped to normalise what we were facing.

Clare and her children

Answering the big - and little - questions

Once I’d said my bit, I gave the children time and space to ask questions. I tried to validate their reactions, assuring them that no question was too small or too silly. My son was quite pragmatic, wanting to know how the cancer got there. He also wanted to know what colour it was, which is something I had to ask the consultant (flesh-coloured in case you wondered!) My daughter was a little quieter.

I knew it was important to be led by the child and not to push how they were feeling.

In her own time, she asked if she was going to get cancer, too? They both wanted to know if I was going to die, of course, and I answered as honestly as I could so that they wouldn’t feel I was hiding things. I was able to say that, although there were difficult times ahead, the doctors were confident they could remove my tumour and give me medicine to get remove stray cells in my body.

As the weeks went on, we found having a calendar a good visual aid for treatment cycles and importantly, we marked a big treat at the finish line! We also involved the children in decisions like – should I shave my hair? Do you want to help shave my hair? What colour wig should I wear?

Involving the children in these decisions encouraged their problem-solving skills and gave them some ownership in a time when so much was out of their control.

Actually, this wasn’t my children’s first experience of cancer. Very sadly, we lost our uncle to a brain tumour two years before. I found this a very hard conversation to have, too. Maybe because the children were younger, maybe because it was the first time I’d had to broach something so hard with them… but mostly likely because the prognosis was very different. Shane’s cancer was terminal. There was no two ways about it – the news was utterly devastating.

Shane Bownes, who was diagnosed with a brain tumour and inspired 'The Perfect Shelter.'

Shane Bownes, who was diagnosed with a brain tumour and inspired 'The Perfect Shelter.'

It was while I was processing these feelings, thinking about how I could talk to the children in a realistic but hopeful way, that I wrote The Perfect Shelter.

Writing The Perfect Shelter

The main character struggles to come to terms with her sister’s unnamed illness, but ultimately finds hope at a very uncertain time. Since my years as a primary school teacher, I have always advocated using stories to broach difficult conversations with children, but at the time I couldn’t find exactly what I was looking for - a book that focused on accepting and living with a difficult diagnosis, as opposed to one about grief. I very much kept my children at the forefront of my mind as I wrote, and my whole family who were inspirational during an unimaginably hard time. Whilst the feelings are authentic and raw in places, I wanted the theme of the book to be one of hope.

Writing the story put me in a much better position to talk to my children about Shane. It was cathartic and a way of processing the unfairness of it all. Of course, a few years later, the story turned out to be even more important than I could possibly have imagined, facing my own diagnosis. The illustrations arrived on the morning of my first surgery. Although it was written with my uncle and auntie in mind, reading the story felt much more than a coincidence. It felt like I’d written myself a little ‘how to’ get through this. You can do it!

Clare poring over Åsa’s beautiful sketches!

Clare poring over Åsa’s beautiful sketches!

Stories can help us remember we are not alone

Naturally, when facing a serious illness in someone we love, we feel scared and vulnerable, and children are no exception. A book can be a gateway into a safer world, where it might be easier talk about and unravel the emotions because we are in another character’s story. In short, they are a place to explore our worst fears.

Of course, there are no easy fixes for most of life’s problems. But recognising and communicating how we feel is a healthy first step into managing a problem. Stories are also a great way of letting a child know that they are not alone in feeling the way they do. There is nothing more comforting than knowing that someone, at some point in time, has had a similar problem to you.

Top tips for talking to children about serious illness

My top tips for using books to talk about serious illnesses with children would be:

- Pick a moment that feels right and get comfortable. Try to be as relaxed as possible, like you would during any other story.

- Show you are interested by making positive comments about what the child sees and hears, and to keep the conversation going. “I see it too!” “And then?” “She does look sad.”

- Reflect and use emotional labelling; “You seem worried/ anxious/ upset…” “This feels important to you.”

- Encourage your child’s independence and problem-solving skills by responding to their questions with open-ended questions. For example, “That’s a good question.” “Why do you think the girl is crying?” How, which, what, where and who questions are good, also.

- Always comment positively and value their responses, even if you don’t necessarily agree. These validate a child’s feelings and will encourage them to share other things with you.

- Be led by the child, at their own pace and time, so that they have the control. If they aren’t particularly talkative, don’t push it.

- Remember it’s ok to get upset. We perhaps don’t want to worry children by letting them see us tearful. But this can give them permission to be tearful, too. Children will learn we don’t have to hold our feelings in and that it’s ok to struggle and be honest about our emotions.

- Remember that with time, love and support, children can learn to be resilient in the face of challenges.