Michael Rosen on talking to children about the Holocaust: 'We need to give them space to express themselves'

Published on: 27 January 2020 Author: Anna McKerrow

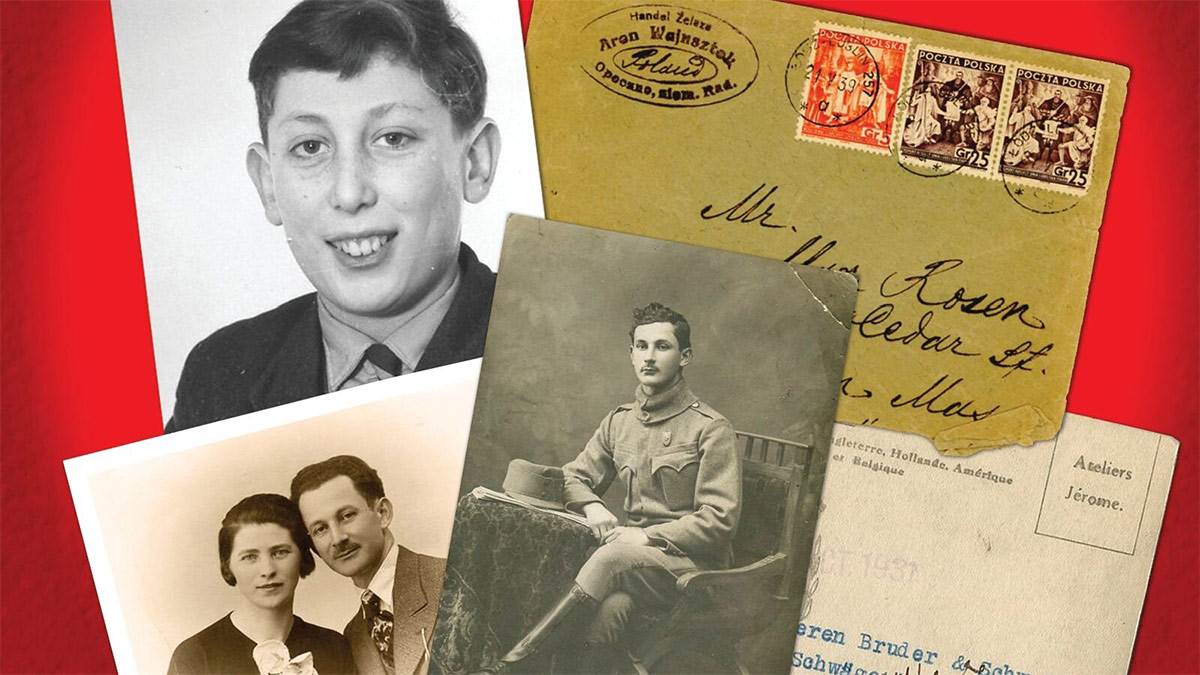

Michael Rosen talks to us about his new book, The Missing: The True Story of My Family in World War II, which is out in January to commemorate Holocaust Memorial Day. In 2020 it will be 75 years since the liberation of Auschwitz, and the end of the war.

Michael, it's so great to be able to talk to you about this amazing and very necessary book. To start, this may sound like an obvious question, but especially now, why should we talk to children about the Holocaust?

Well, I guess one of the reasons to talk about it is that the Holocaust is one of the most recent huge genocides of the last 100 or so years. There have been other genocides - Rwanda, the terrible massacres in the Balkans and so on - but the Holocaust has a special position in this horrible league of crimes, because it was so calculated, scientific and industrial.

Rather than it being suffering born out of war, it was a calculated move to remove a people from Europe. It's also distinctive because it happened over such a huge geographical area, all the way from the western seaboard of France to the edge of Russia. So we're talking about that kind of scale - it's not just a matter of numbers but of intention, the breadth of it, across so many countries and with so many collaborators. We also have to talk about it to fathom how people could have behaved like that.

The fact that The Missing is the story of one family provides children with a really accessible way in to starting to understand a pretty overwhelming subject.

It's impossible to encompass the detail of what happened, but in order to understand it, including the way in which people were picked off, people who were just going about their lives and trying to survive - that part of the story is best told to us through individual eyes and individual cases, I think.

You can say things in terms of numbers; you can say things about people being put on trains, but until you see the face-to-face immediacy of it, and how people like my uncles responded, like my uncle Jeschie and aunt Rachel who run away, but the net closes around them - they haven't done anything wrong.

Children are likely to think that if people are being chased by the authorities it's because they've done something wrong - that's what they're brought up to believe. The police are chasing that man down the street because he did a burglary, or worse. So we're explaining to children that this is the complete reversal of the right order of things, because here's a situation where the authorities are doing the wrong thing.

That is what my relatives' story shows: they were doing nothing wrong and yet the authorities were closing the net around them. I hope children will see that as one part of what was so wrong about it all.

Have you done school events talking to children about the Holocaust, or other work in teaching about what happened in World War II?

Yes, I've spoken to a lot of children about this, and I've worked a lot with Professor Helen Weinstein at History Works TV in Cambridge - we've done a project around Holocaust Remembrance for several years. I've told these stories many times and that's actually what led to me creating the book - I was doing this work for History Works and I thought it would be really useful to have a book that went with it. I turned the narrative that I was saying and the poems I was writing and performing into the book.

When you talk to children about the Holocaust, how do they respond?

I think the key thing in talking to children about the Holocaust is to give them a space in which they can express something. So rather than whacking them over the head with it, it's important to give them a space to write about things, do drama, music or dance.

It might be that they respond directly to the story I've told them, or it might be that they consider other forms of persecution, refugees, migrations that end badly, whatever it might be - as long as it's something where there's a grounding of empathy.

For example, I saw a group of children do a mime based on Jeschie and Rachel's story and it was just stunning. One person told the story very simply and about ten others did a mime. There was no violence, no shouting and screaming or rolling on the floor, it was just a very calm mime - and I just thought, 'Wow, that's so moving'. It was almost like looking at a picture book but enacted by children.

The process of researching what happened your great-uncles and aunts you describe in the book was really difficult and often discouraging because of lost or damaged records, and it took a long time to get to what you know now - but what was the biggest breakthrough you had in the research?

The biggest breakthrough was a collection of letters turning up when somebody died. A very distant relative - not even a blood relative, just someone that had married into the family - he died, and for some extraordinary reason that none of us really understand, he was the one who had these four letters that had come out of France and Poland to the American relatives. That was the key breakthrough.

Until then, we had no written or photographic record of what happened to my father's uncles. It was only when they appeared that suddenly we had something, and that enabled me to unpick the rest of the story.

It must be a great relief (albeit a story with a sad ending) to have found out what happened to Jeschie and Rachel - there are so many people who have mysteries like these in their family history, who still don't know what happened to relatives, either in the Holocaust or in other situations.

Absolutely. It's quite a nice thought for myself that, given the kind of education that I had - doing a degree, learning French, doing a Masters, a PhD - it equips you with a kind of terrier-like quality when you come face-to-face with information.

So instead of treating information like this wall of stuff that you can't possibly do anything with, I just think of it like an opportunity: the potential is there! It's a different state of mind. If something's in French, then you think, 'Ah, well, I'll translate it. Even if it's in German, I don't have much German, but I can work it out with the help of a dictionary!' It's a rewarding feeling.

I'm rewarding myself for having done all that education and being able to put it to good use. I can feel my parents at the back of my mind - my dad, in particular, being pleased I've put my education to that purpose.

There are some brilliant recommendations at the back of the book of fiction and non-fiction books for kids about World War II and the Holocaust as well as about refugees and displaced people in general. Which ones are your particular favourites?

The non-fiction title I particularly like is Beyond Courage: The Untold Story of Jewish Resistance During the Holocaust by Doreen Rappaport, which is published by Walker Books. The Island by Armin Greder is a great picture book which works very well at getting children to understand persecution.

I teach the MA in Children's Literature at Goldsmiths and some of my students are teachers. They've worked with that book and the conversations children have had around that book I found very affecting. That book has done a lot of good work, put it that way!

The Missing: The True Story of My Family in World War II by Michael Rosen, published by Walker Books, is out now.

Topics: Historical, War, Family, Politics/human rights, Interview, Features

Add a comment