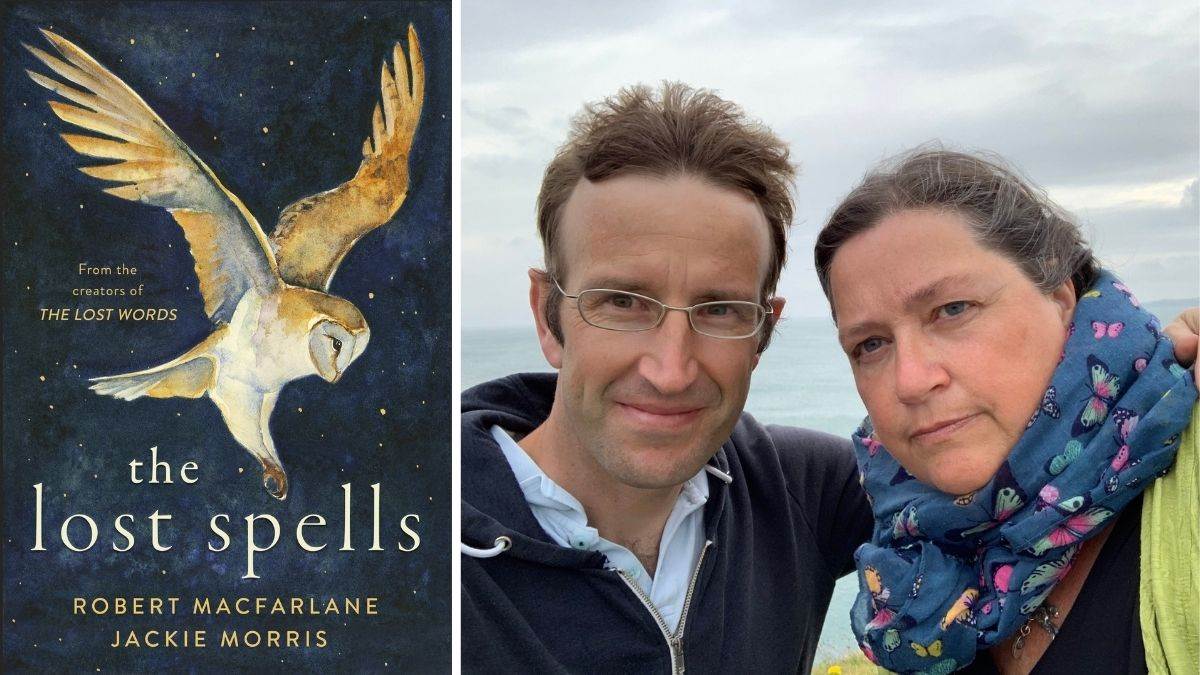

"It's time to become wilder": The Lost Spells and the magic of the natural world

Published on: 15 December 2020

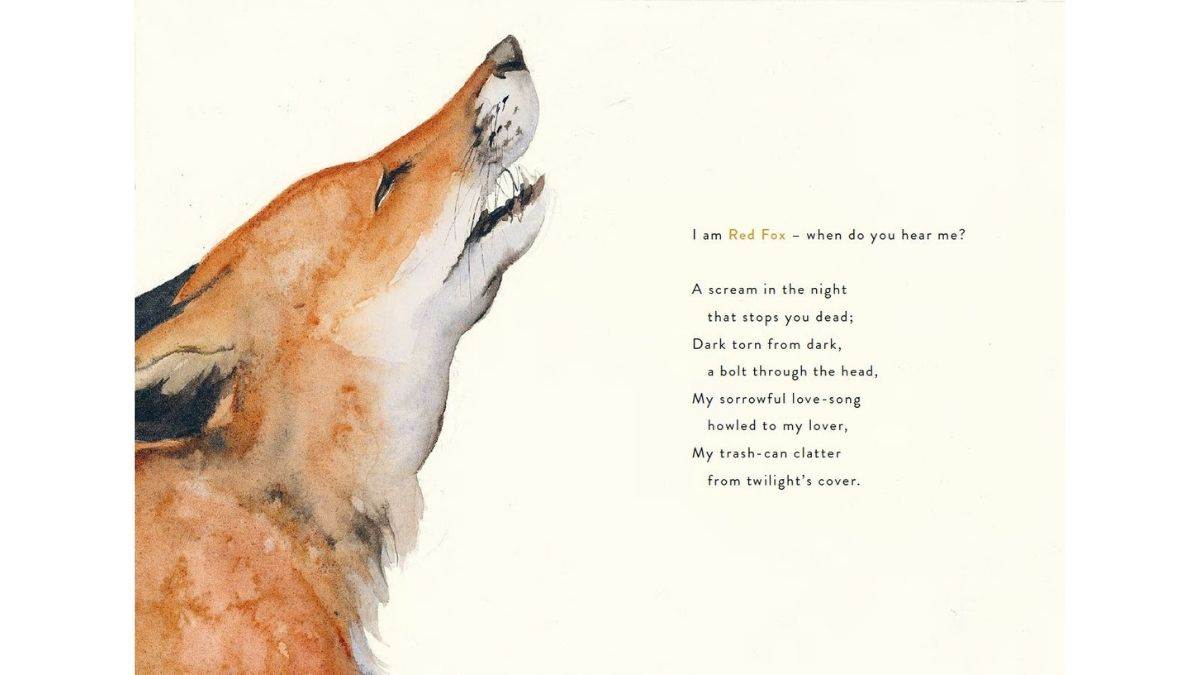

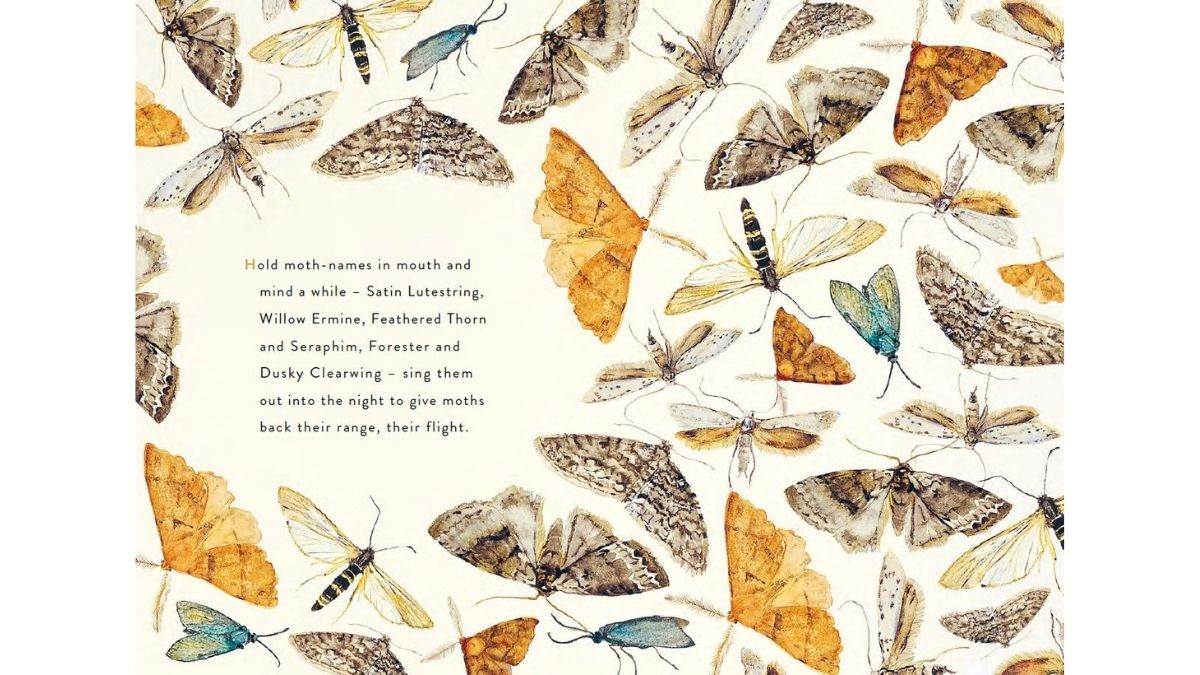

The forgotten beauty of the plants and flowers of the British countryside, the wiley urban foxes that dig through our bins, the colourful names of the moths that flutter by... all the overlooked wonders of nature are celebrated in The Lost Spells.

Creators Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris answer our questions about how we can look after, and be inspired by, the natural world.

The Lost Spells is a beautiful, immersive book of poems and pictures that really encapsulate the wonder and magic of British nature. Why are you both so passionate about passing on that wonder to younger generations?

Thank you. It was hard work, but beautiful to do, and it’s always good to hear when your work speaks to people.

It’s not really about passing on the wonder to the next generation, because that will be too late. It’s about reawakening the utter awe and wonder of what an astonishing, complex and interconnected world we live in for adults. You can do this through books for children, because this is the place where adults and children meet. When parents and carers, teachers and friends, share the book with children, hopefully they will build a love for the wild world in a new generation even as they remember things that may have become lost to them, drowned out in the noise of modern life, forgotten, made seemingly irrelevant in our day to day challenges.

As to why? Simply because I would like to survive, and for my children’s children’s children to prosper, in a world more understanding of the complex web of life.

The Lost Words aimed to educate children about the names of animals and plants that had been erased from common knowledge – where does The Lost Spells come in? We can see that the pieces in the book are a little like spells in the sense of being evocations of the true nature of things. Was this what you were aiming for?

The words had been lost from the vocabulary of children because they were also gone from the vocabulary of adults. I met many a teacher who did not know what a wren, a weasel or a starling were.

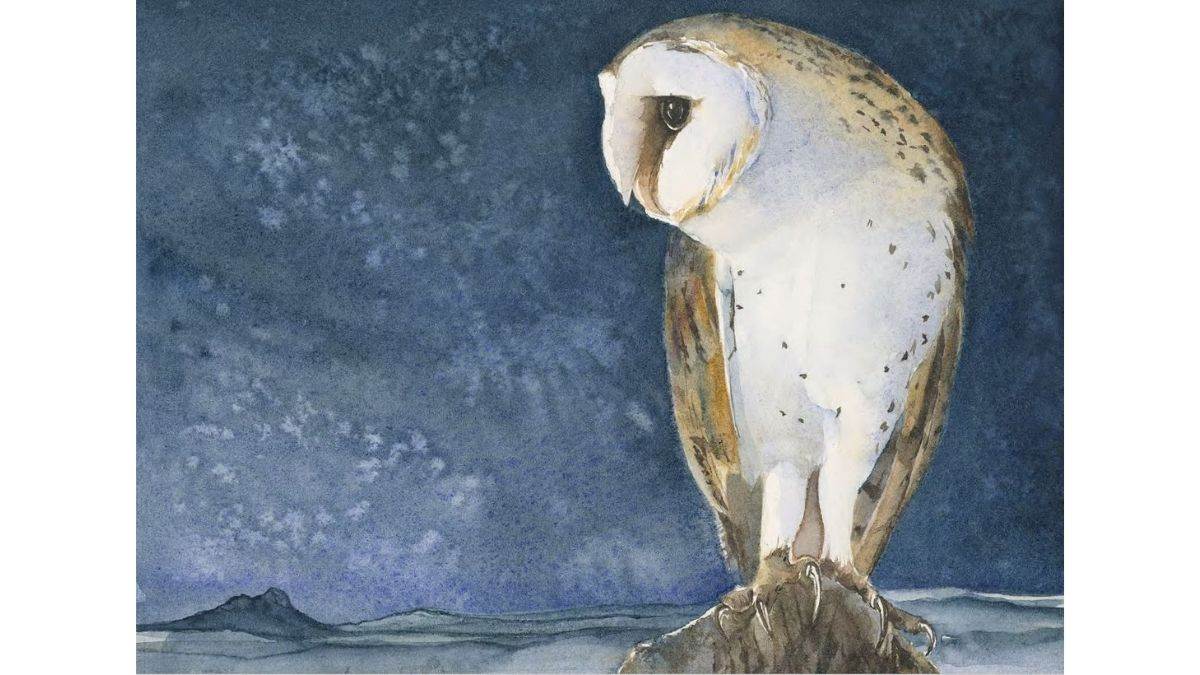

I wanted to create a book that celebrated the wild world further, that was small enough to be carried in a pocket or a bag, that was rich in colour, shape and form. Spells had been growing, around The Lost Words, being scattered around the land. Barn Owl was written for Suffolk Wildlife Trust, others had their own origins. Red Fox, a spell written for the astonishing Lost Words Prom, came to light and the feeling grew that it was time to gather the spells into a new book. Twelve at first, but somehow this grew to twenty, and then Silver Birch whispered its way into Robert’s mind, a witchy lullaby of a spell, for sleeping. They move in a different way these spells, through night and day, from earth to air to sea, and then to sleep.

You had a brilliant reaction to The Lost Words from children and adults alike – do you think we need nature more or less than before? Do we need to repair our relationship with nature?

We are nature, but only a very small part of it. We have little choice but to repair our relationship, as the alternative is unimaginable. We’ve lived through a few generations where the feeling was that we could dominate, full of the cleverness of ourselves, like Peter Pan.

How do you think the events of 2020 have affected our relationship with nature?

My hope was that many had woken up to hear birds for the first time. Such dark and difficult times of loss and sorrow for many. My hope was that people would address how we exploit our environment, often to a breaking point, usually for financial gain, that causes huge wealth for some, massive poverty for others.

For this in lockdown in cities there became a desperate need for people to go to wilder places. Instinctively we understand that many of us need that space for our own mind’s balance. There was also a growing awareness that flying is maybe not a sustainable thing for the future.

But politicians and leaders only seem to envisage a future of returning to ‘normal’ and ‘business as usual’. Until we change the balance of government, ditch career politicians, have think tanks which contain artists and writers and thinkers outside the field of economics then nothing will change. To change we need to imagine better ways to live in harmony with, not in dominance of, our environment. Because in deeper time we will realise we were not as clever as we thought we were. There is an intelligence in the non-human world that we need to learn, by looking, listening, thinking and dreaming. It’s not a new thing. Humans have lost so much of this wisdom as we have become urbanised, ‘civilised’. It’s time to become wilder.

The Lost Spells is much smaller that The Lost Words (we actually love the new format, it’s like having a pocketbook that erupts with magic every time you open it) – was there a particular reason for the different size?

The size and shape of a book is just one of the things that is as important as the content. The Lost Words is a big creature, one to gather around. ( It can also be used as a shield to hide behind, and keeps the rain off if you use it like a hat). The Lost Spells was designed to be portable, to carry in bag or pocket, or hand. It’s a talisman, and our hope is that it will be carried out into garden, park, meadow and mountain. You can speak it aloud, or keep it close. The size means the spells unfold as you turn pages, and each spell is bounded or bordered by double page images. It has a weight to it. I love the design on the case. And the key at the back. The design is by Alison O’Toole again, and she’s managed to make space in the book, despite its small size. When you open it, it does seem to grow.

Do you have any favourite books from childhood that were about nature – or books of poetry perhaps – that you really loved? Do you think they informed your work now in any way?

I was a late reader, but when I discovered the books I loved I ate them up. The Call of the Wild by Jack London sang to me, and Tarka the Otter by Henry Williamson. I wanted to be a wild otter in the river. Reading the book as an adult I can’t believe how rich the language is, how dark the tale.

I also adored Tunnicliffe’s illustrations, particularly of birds. My Friend Flicka was another book I loved, which also has illustrations by Tunnicliffe. And my amazing Reader’s Digest AA Book of British Birds which I would pore over, learning the shape and the names of birds.

Topics: Non-fiction, Picture book, Poetry/rhyme, Animals, Environment, Nature, Features