Are you sitting comfortably? Then here's the Jackanory Story

Published on: 24 January 2017 Author: Liza Millett

Joy Whitby, creator of Jackanory – the BBC’s groundbreaking reading show that ran from 1965 to 1996 – tells us how the programme came into being, and why we’ll never lose our appetite for stories to enrich our lives.

My mother came from Russia and I was born in Finland, so in my toy cupboard as a child there were picture books from abroad, as well as English tales.

My parents read to me at bedtime. My elder brother told me ghost stories on our walks. When I was asked to devise a daily programme for children at teatime on BBC1, it wasn’t surprising that I chose storytelling.

A production team was appointed and we started thinking of names for this new programme.

Two members had a brainwave. ‘How about Jackanory?’

It was perfect. If you don’t know the old rhyme, it goes like this:

I’ll tell you a story

About Jack a Nory

And now my story’s begun.

Tell me another

About Jack and his brother

And now my story is done.

Stars of storytelling

Jackanory had to fill a 15-minute slot every week day – as it turned out, for 31 years. The budget was small and we were studio-based so we had to be inventive.

One week, there might be a collection of related picture books – Peter Rabbit on Monday, The Tale of Mrs Tiggy-Winkle on Tuesday, and so on. Another week, there might be a novel, such as The Children of Green Knowe, adapted in five parts.

The breakthrough idea was marrying stories to ideal storytellers and an early coup was getting Sir Compton Mackenzie to record a week of Greek legends. He was a celebrity. A literary lion. Mesmerising. But at the other end of the scale was Eileen Colwell, a tiny middle-aged librarian in Hendon, a pioneer of storytelling to children.

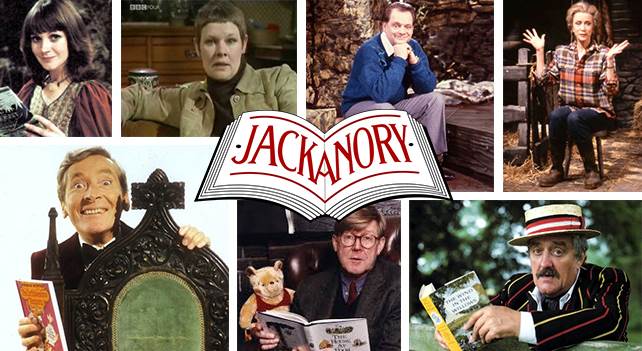

When Jackanory became established, actors queued up to appear on it. Judi Dench, Kenneth Williams, Alan Bennett… The list of stars was astonishing.

Illustrating the tale

From the beginning, we experimented with different kinds of presentation. Talking straight to camera. Or using images projected on a screen behind the storyteller, so that he or she appeared to be sitting in a garden or by the sea.

I remember the younger Steptoe, Harry H Corbett, dropping by parachute to land on the white, wrought-iron bench that was a regular feature of Jackanory for many years.

Some stories had wonderful illustrations by artists such as Arthur Rackham. Cutting away from the presenter to his pictures was an obvious enhancement. And, increasingly, our graphics unit provided illustrations for stories that had no pictures.

Food for the imagination

The digital age has changed our viewing habits but not our appetite for stories.

However we access them, child or adult, stories enrich our lives. They enlarge our vision, introduce new ideas, show us how other people think and live. They challenge our wits. Make us laugh and cry. From the days of sitting round a fire entranced by the saga of Beowulf, stories have fed our imagination as much as bread and butter feeds our tummies.

I visited our local bookshop last month to discuss the launch of my own children’s novel, a reprint of Grasshopper Island, first published in 1971. Daunts was overflowing with books for Christmas.

How many were story-based? The assistants estimated at least two-thirds.

Joy Whitby’s children’s novel Grasshopper Island, is illustrated by Carol Lawson and based on Joy Whitby’s landmark TV show.