Celebrating Roma, Gypsy and Traveller stories

Published on: 03 April 2017 Author: Alex Strick

Alex Strick explores the absence of characters of Roma, Gypsy and Traveller (GRT) heritage, and meets the creators of two new books hoping to redress the balance.

There's no doubt that all children need to be able to find themselves in books. They also need to learn about those whose lives and experiences might be different from their own.

Yet rarely do characters of Gypsy Roma Traveller (GRT) heritage appear, and where they do, we see some tired stereotypes and misleading messages.

Historically, gypsy characters have tended to be heavily romanticised - dark strangers and mystical fortune tellers. Or, more worryingly, we see thieves and troublemakers.

Social attitudes

In the 2014 Global Attitudes survey, 50 per cent of people in Britain admitted to having an unfavourable view of Roma people. The Brexit result also brought a fresh surge of animosity. And yet, such is this community's history of negative reactions from authority (and, indeed, society as a whole), that this new wave of hate crime went largely unreported.

Similarly, various studies (including a longitudinal study by University College Northampton) have found that negative treatment and name calling of Traveller children in schools is disturbingly commonplace, but children are reluctant to report incidents to teachers.

Redressing the balance

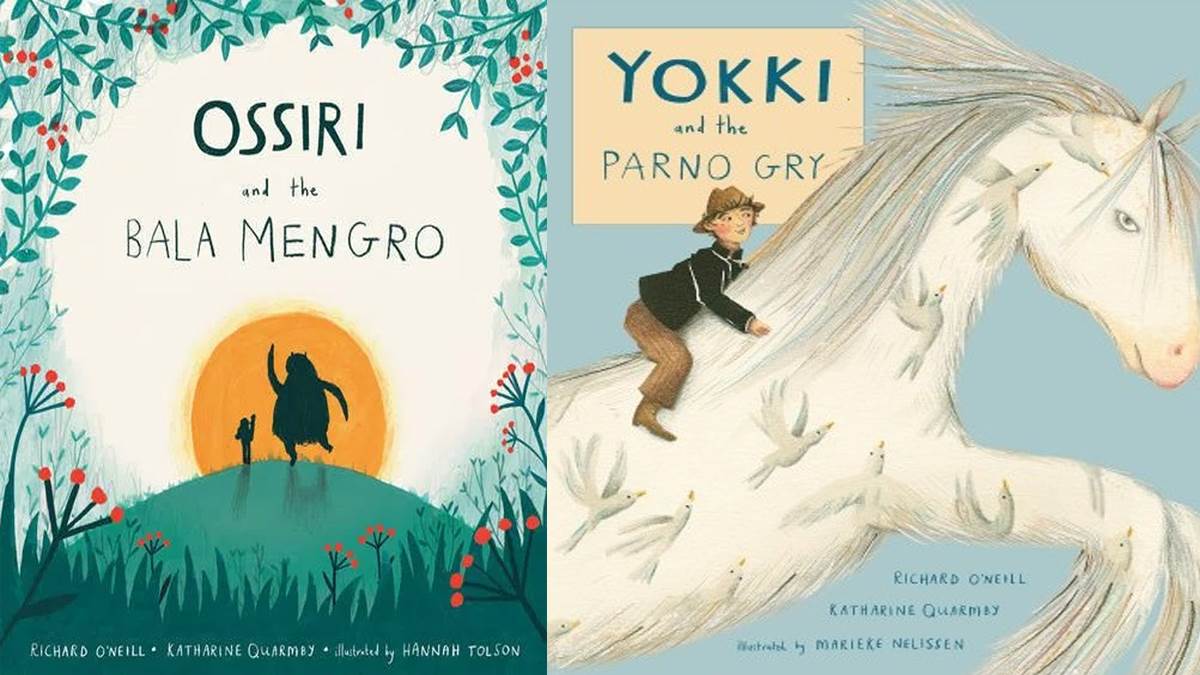

Co-authors Richard O’Neil and Katharine Quarmby (and their publisher Child’s Play) hope that their recently released picture books Yokki and the Parno Gry and Ossiri and the Bala Mengro will help change attitudes.

Independently, both Katharine and Richard had long dreamt of creating such books.

Author Katharine Quarmby had been involved in challenging racism and promoting inclusion for many years. Her first picture book Fussy Freya features a dual heritage protagonist and Katharine often receives positive feedback on the casual inclusion of a dual heritage family. As with most facets of diversity, Katharine feels the key is not always 'making it centre stage', but also finding subtler approaches.

Katherine was also one of the first journalists to bring the plight of the Travellers at Dale Farm to national consciousness. This was when dozens of families, many of whom camped legally, were evicted from their Traveller site in Essex, by taser-armed police.

She is painfully aware of the long history of animosity towards GRT communities, dating back to medieval times, and the absence of positive depictions in books. She notes that, as a result of this animosity, there are almost no Gypsy and Roman folk tales in mainstream literature – instead, these were kept very close to the heart of the Gypsy and Roma community.

Meanwhile, Richard O’Neill grew up in the North of England in the 1960-70s. The life he was born into was nomadic. Some of the stopping places were hundreds of years old – he talks of ladies wearing long Victorian skirts and headscarfs.

Born in a caravan and living communally, it was only when Richard started school that he realised his lifestyle was any different to that of his peers.

'You quickly realise that the expectations that people have of you are not very high,' Richard tells me. 'This is still the case with some kids today.'

Challenging stereotypes

There is a very real need for books like those above, which challenge some of the stereotypes that have developed over many years.

For example, contrary to popular belief, GRT families don't all live a nomadic lifestyle. Richard puts it very well: 'If you live in Spain, that doesn't make you Spanish.'

These books instead show important new perspectives, vital if children are to develop respect and empathy.

'You can't just stop people talking,' Katharine tells me. 'You also need to provide other images and positive messages.'

The books celebrate the skills and traditions of this community (for example, illustrating their self-sufficiency, reflecting the importance of music and showing people recycling old materials to create new instruments). Crucially they do so without falling into the trap of defining the characters by such traits. The children are fully rounded personalities with strengths and weaknesses like any other child.

The families depicted in both books are hard-working and honest people who are respected by settled people for the skills they bring. Historically, many harvests depended on them, as they do on migrant workers today.

And of course, they show us that they GRT communities are an important part of the storytelling tradition: they are story makers and story keepers.

A message of hope

The challenges faced by the GRT community are of course not dissimilar to those experienced by other minority groups. The landscape is awash with stereotypes, so books like Yokki and the Parno Gry and Ossiri and the Bala Mengro can offer a message of hope to all.

They tell GRT children that their stories and histories are of genuine interest and they can be proud of them. They validate these children and their experiences - but they also enrich the experiences of all children.

'I hope these books help illustrate our human-ness,' says Richard.

There is a sense that traditionally, a character from the GRT community might have appeared in a book simply 'to add a bit of spice' or to tick a box. Let's hope this is starting to change.

You can write about anything you like, the two authors agree, but you must remember that what you write has ramifications for those people you write about.

And for some such people, it can feel as if there is no voice, no right of reply.

Surely these books represent one.

Topics: Politics/human rights, Diversity (BAME), Features