The extraordinary true story of my family’s escape from Nazi Germany that haunts my debut children’s book

Published on: 9 Tachwedd 2021 Author: David Farr

Playwright David Farr has written an exhilarating fantasy-adventure novel for children – The Book of Stolen Dreams – about a brother and sister’s flight from their homeland. He reveals the real-life story behind the fiction…

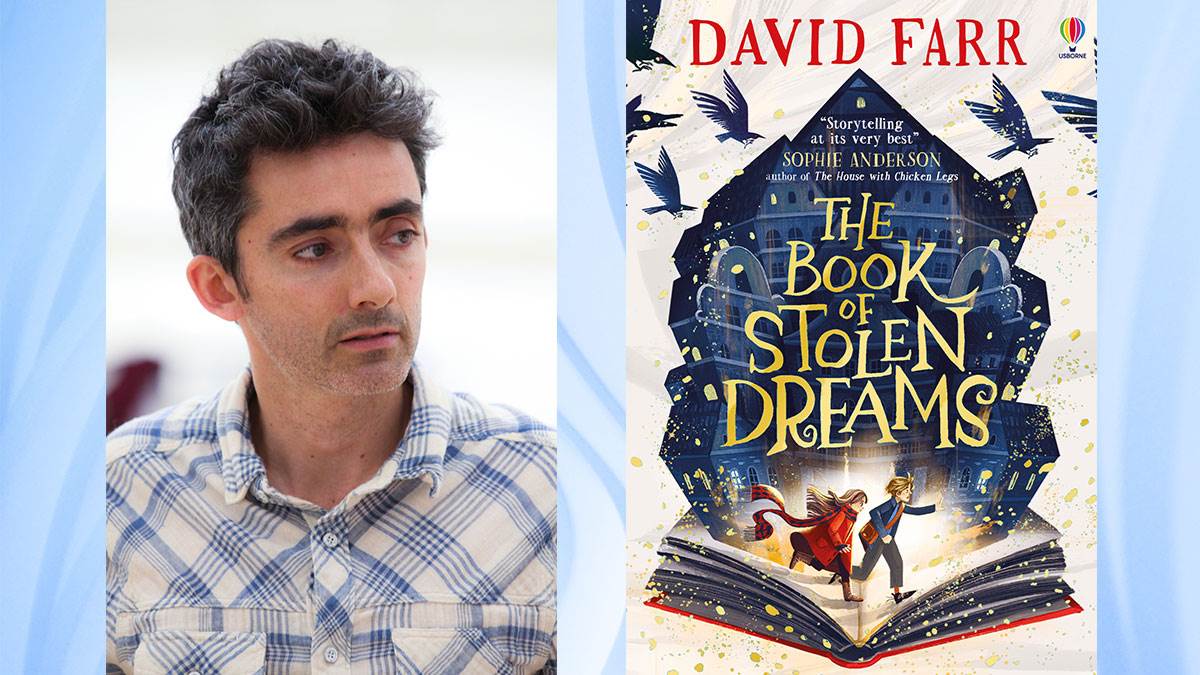

Writer David Farr and his children's novel The Book of Stolen Dreams

Writer David Farr and his children's novel The Book of Stolen Dreams

The Book of Stolen Dreams, which is published this week, takes place in a fictional world, ruled by a vicious despot, Charles Malstain. A brother and sister, Robert and Rachel Klein are entrusted with a very special book by their father, shortly before he is imprisoned by Charles Malstain’s authorities. Together, Robert and Rachel embark on a rollercoaster adventure to discover the magical secrets of the book and why Charles Malstain wants it so much. They lose members of their family, they lose their home, they are forced to foreign lands… But they never lose the determination to honour their father’s faith.

My book is fictional, set in my invented world of Krasnia. But there is another book that sits behind it. A book that documents very real pain and loss. It’s like a ghost that haunts The Book of Stolen Dreams.

It’s a slim, blue volume and it sits on my mantelpiece. It’s called One Small Branch. It’s self-published, 14 pages in all, and it contains the reminiscences of my great aunt Ruth, recalling her German-Jewish family, her upbringing as a child in 1930’s Dusseldorf, and the evening in 1935 when her mother (my great grandmother Aennie) stood up at dinner and said to the whole Elkan family: ‘I have read Hitler’s book and it is clear that we are in grave danger. We are all going to leave.’

A time of books and laughter

The Elkan clan, it is said, came originally from Spain; Sephardic Jews who were expelled by Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492, and made their way to Western Europe, settling near the Rhine. For hundreds of years they lived in various Rhineland towns and cities, becoming more and more German, loving Bach and Beethoven, Heine and Schiller.

My great grandfather Josef was a dentist who served for Germany in the First World War, desperately trying to keep soldier’s teeth in order – first in France and then on the Eastern Front, where he also repaired facial injuries. (I still have his copper dentist’s pot and keep important things in it.) He returned emaciated but alive six months before Armistice Day. He won the Iron Cross.

After the war, the family settled into life in Dusseldorf. Josef and Aennie had three children. Initially, there were hard post-war times, with Aennie working all night in a bank. But then prosperity followed. A dentist’s practice, evenings of violin and “lieder” (setting poetry to music – Josef was a great singer), a strong social community, and walks outside the town along the Rhine. My great aunt remembers many books and much laughter.

And then everything changed.

Society split in two

In 1929, the Wall Street Crash came, and hard upon it the rise of Hitler. Hundreds of years of German living was suddenly and irrevocably placed under vicious and relentless attack.

The Nazi assault on their lives and livelihoods was, to teenage Ruth and her younger brother Robert and older sister Anne-Marie (my grandmother), mystifying and utterly shocking. Ruth’s Girl Guides group was suddenly split in two. She remembers how school-friends suddenly ‘appeared in brown leather jackets, becoming more distant and polite’. Three months before her “Abitur” (equivalent to A Levels), Ruth was expelled from school. For a clever young Jewish girl, this was devastating.

As the family’s favourite music, Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier, battled with Nazi oompah bands marching the streets below the apartment, Ruth’s mother began to read Hitler’s rambling autobiographical polemic Mein Kampf. And by the time she finished it, and with life increasingly intolerable, she made the decision to get the family out.

And so they did – one by one.

Perilous journeys through Europe

My great grandmother found a sponsor in England to help relocate the family – the wonderfully named “Mrs Franklin-Kohn”.

My great uncle Robert (just 12 at the time) went first. He travelled alone and was put in a school in Swanage.

Ruth went next. I remember her telling me, when she was 80 and I was 30, as we sat in her neat little garden in the Buckingham town of Amersham, about her perilous journey. She took the train to Holland, always anxious her papers would be rejected and she would be turned back. Then the sea journey from Holland was hijacked by a viciously metaphorical storm, the boat unable to dock at Dover due to the high waves and forced to redirect to Newhaven. She was violently sick.

Ruth arrived in the UK as a migrant, a “B” foreigner as it was called at the time. She was immediately put to work as a “daily” (a cleaner) in Poole hospital. She was 16 and should have been celebrating those A Level results.

Her sister Anne Marie followed, via Italy. And, finally, their parents came in 1938 after years apart.

The family’s dramas were not entirely over. When war broke out, they were all interned as suspicious “enemy aliens” to the Isle of Man (the men) and Hackney (the women). But they were safe. Miraculously, they had all made it.

Ruth’s Jewish friends in Dusseldorf – and most of her extended family – did not.

The voices of my book

My grandmother (Anne Marie) died in her late 40s of breast cancer and I never knew her, so great aunt Ruth became the touchstone to the past. I loved her. Her voice, her soft mittel-European accent… I can hear it today. It is the voice of my book.

Ruth never went back to Germany. Although she positively embraced her British nationality and was always grateful to this country, she missed being German more than anything. She died in 2007 and I spoke at her funeral. I never cry but that day something strange overcame me, and I had to stop my speech halfway through for a while.

So The Book of Stolen Dreams is for her and for Robert.

I hope it honours them.

More books about wartime and fleeing persecution

Check out our booklists for BookTrust recommended reads on these tricky topics for children.

Books about World War II

From classic favourites to more recent titles, these books for children take a variety of different approaches to representing the events of World War II.

Books about refugees and asylum seekers (older children)

Since asylum can be a confusing issue for children (and even adults), here are some books that explore what it really means to flee your home and have to start your life over.

Topics: Historical, War, Refugees/asylum, Features