How Michael Rosen's COVID-19 recovery inspired an unusual book about a walking stick

Published on: 4 Tachwedd 2021

Former Children's Laureate Michael Rosen became seriously ill after catching COVID-19 last year. In this interview, he explains how his long road to recovery inspired an unlikely children's book hero and how he hopes his story might help people talk to each other...

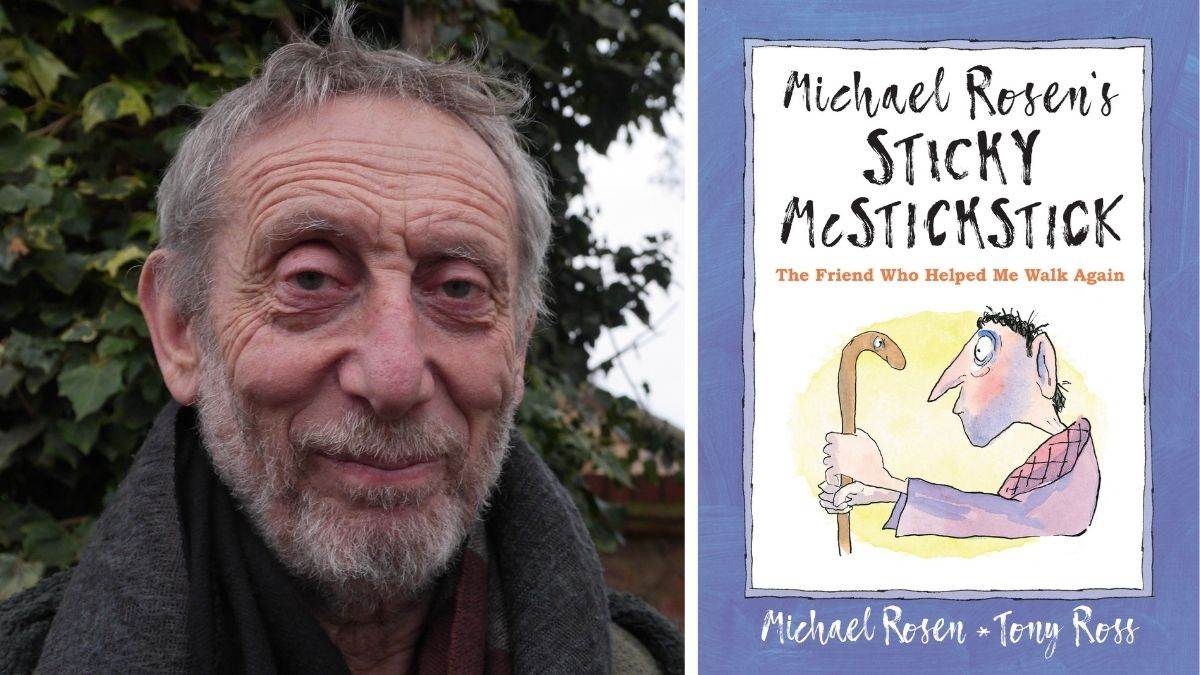

Michael Rosen and the cover of Sticky McStickStick

Michael Rosen and the cover of Sticky McStickStick

Hi Michael. How are you?

I’m fine. I’ve just been at the Cheltenham Festival accepting the CLIPPA Award for my book of poetry On The Move, illustrated by Quentin Blake. But, yes, I have been ill. There’s permanent damage. I can’t see out of my left eye and I can’t hear with my left ear. I have numb toes. I feel a bit dizzy every now and again. I’m quite strong but there is a bit of a problem with my balance still.

You got Covid in March 2020. What happened?

I was ill with what felt like flu for about two weeks, but then I started getting worse: my wife, Emma, noticed that I couldn’t catch up with my breath. At that point it wasn’t possible to get tested or go to a doctor; we weren’t even supposed to go to A&E, so we rang 111. I spoke to a paramedic and he decided that I didn’t have Covid, but Emma wasn’t happy so she called a friend of ours who is a GP and a neighbour. She came over in the morning and then came back in the evening with an oximeter and tested how much oxygen was in my blood, and it was way too low: the reading I got meant I shouldn’t even have been conscious. So, our GP friend rang A&E to say we were on our way and she and Emma bundled me in the car – I couldn’t walk by then.

They got me to the hospital and I was taken straight into intensive care. I seemed to recover for a few days but then dipped very suddenly again, and they put me into an induced coma for 40 days.

I slowly came out of it, and then they took me to the rehab hospital.

All in all, I was in hospital for about three months. I was very seriously ill because I had blood clots in my lungs, and after 40 days in a coma, your body is basically completely incapacitated. I couldn’t do anything. I couldn’t walk. I couldn’t really move my legs, and I was confused and delirious as well.

When I got to the rehab hospital, that was a big change for me after being in intensive care, and that’s really where the Sticky McStickStick thing comes in.

Was that when you started thinking about writing Sticky McStickStick?

Oh no, I was too busy learning how to walk! I think what happened was that I tweeted a couple of times that my walking stick, Sticky McStickStick, was helping me: people seemed to find that funny. They said, oh, write a book about Sticky McStickStick! So I tried writing a book from Sticky McStickStick’s point of view, but it sounded a bit fey. So, I thought I’d just tell it honestly, like I’d been telling people I knew about it.

I sent it to Walker, and they just laughed and said it was great, and very cleverly paired me with Tony Ross who captured the poignancy and humour of the story brilliantly.

Tony’s illustrations are just perfect, aren’t they?

Totally! He’s captured me and my plight but without dwelling too much on the poignancy of it. These things have a comic aspect; there’s something slightly absurd about human beings, all across the planet, trying to survive.

As humans, we’re desperately clinging to life, which is good, and trying to make life better for ourselves.

It’s quite interesting that physiotherapists don’t take no for an answer if you say “I want to go back to bed” – like you see in the book – they say, well, you can, but remember I’ll be coming back in the morning. You say “No, no!” and they say “Yes, yes! To the gym!” I was like, what? The gym? The book shows this whole thing exactly as it was. I thought, go to the gym? What do you mean? I can’t even swing my legs out of the bed!

I liked the mobility of a wheelchair – I could wheel around in it for maybe twenty minutes without getting tired, but I could only walk four steps. Physiotherapists don’t let you be lazy, you see - that’s part of the humour of the book. Whatever stage you’re on, they say you have to move on to the next one.

It’s lovely at the end of the book that Sticky McStickStick is still there in the hallway, a friend who helped you learn to walk again – just in case you need him again.

That’s right – I do wonder whether there might be a time when I turn back to Sticky McStickStick. It’s a thought that crosses my mind.

Michael Rosen

Michael Rosen

The dedication in the book thanks your family but also the doctors and nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and hospital workers that saved your life. Were there any key moments with those people in the hospital that spring to mind?

A powerful one as far as children’s books is concerned is that I once turned to one of the occupational therapists, Emma, and said rather glumly “Well, I don’t suppose I’ll ever do a show for children again,” – before I got ill, I was in schools doing shows for 300 or 400 children. I’d been doing it for 40 years. I thought, that’s the end of that chapter but it was a shame because it was something I loved doing.

But Emma said she didn’t see why I should stop doing the shows. I thought, is she saying this to cheer me up, or does she really think that? I felt so feeble at the time. It’s so hard to explain how it feels when you’re that weak, physically.

So I laughed ruefully and we left it at that. But then, last week, I did two one-hour shows at a theatre, and I could do it! I had a nice lie down inbetween shows, which I’d recommend to anyone. So, Emma was right and I was wrong, and I’m really happy to have been wrong about that. Emma the occupational therapist at St Pancras Rehabilitation Hospital.

Another lady, Ashima, stood me between two parallel bars and asked me to throw a balloon. You can see this in the book. I couldn’t throw the balloon.

All my stomach muscles had gone, so I couldn’t lift my arms up. I couldn’t believe that I couldn’t even hold a balloon.

But Ashima knew what the stages were that she had to take me through so that I could get stronger again. She could predict how long it would take for my muscles to start working again. But I was thinking, this will never come back. Thankfully, Ashima and Emma were right and I was wrong.

You wrote a lovely note to reader at the end of the book. What would you say to children and families about being ill?

We all get ill – we’re human beings, that’s what we do. We get ill and we get better. But sometimes it’s difficult. I remember having whooping cough as a kid and it seeming to take forever to get better. At the same time, we also get old, and you don’t get better from being old!

I hope that the book opens up a window for people to think about what it means for people to get better, or not get fully better.

If people are walking with a stick, it’s not that we’re bad or wrong in some way; it’s just one of the ways we are as human beings. I hope maybe that a child reading Sticky McStickStick with a grandparent can ask them, why do you have a stick, Nanna? And Nanna can say, I’ve got a bad knee and the stick is helping me.

As humans, we’ve invented these things like sticks and crutches and wheelchairs, and they’re all helping us be in the world, not just locked up in our kitchens. Sticky McStickStick give us a place to talk about that. That’s what books do. Quite often we think books are an end, but they’re a starting point – I hope that this book is something that will encourage people from different generations and different human conditions to talk to each other.

Sticky McStickStick has similarities to your book The Sad Book in terms of being a book to inspire conversation about difficult things.

Exactly. I think that it’s important to write about these things in an honest way. Children’s books give us opportunities for fantasy, which is great – I love fantasy! But they also give us a space for truth. In having written The Sad Book in the first person – I, this is me, this is my reaction to my son dying – that’s honest. With Sticky McStickStick, this is me, Michael Rosen, telling my story. There’s an honesty to it. People can say, hey, look, this did happen to this guy. All right, there’s some funny pictures, but he’s like that. But I hope people will think, we can see that going on around us as well.

What’s next for you, book-wise?

I’ve got a few picture books coming up, and one with Michael Foreman with Scholastic and the British Legion next year about World War Two, told by letters sent between two Jewish cousins: one boy in London and one boy in Poland. We don’t know as we read if either boy is going to survive, and the story is framed by the English boy reading the letters to his class at school.

That sounds amazing! We will definitely look forward to reading that. Thank you, Michael.

Topics: Friendship, Illness, Features, Feelings

Waterstones Children's Laureate: Joseph Coelho

Poet Joseph Coelho is the Waterstones Children's Laureate for 2022-24.

The role of Children's Laureate is awarded once every two years to an eminent writer or illustrator of children's books to celebrate outstanding achievement in their field. Find out what Joseph's been up to.