The truth about disabled characters in children's books

Published on: 05 July 2023

Author James Catchpole shares his thoughts about how disability is portrayed in children’s fiction.

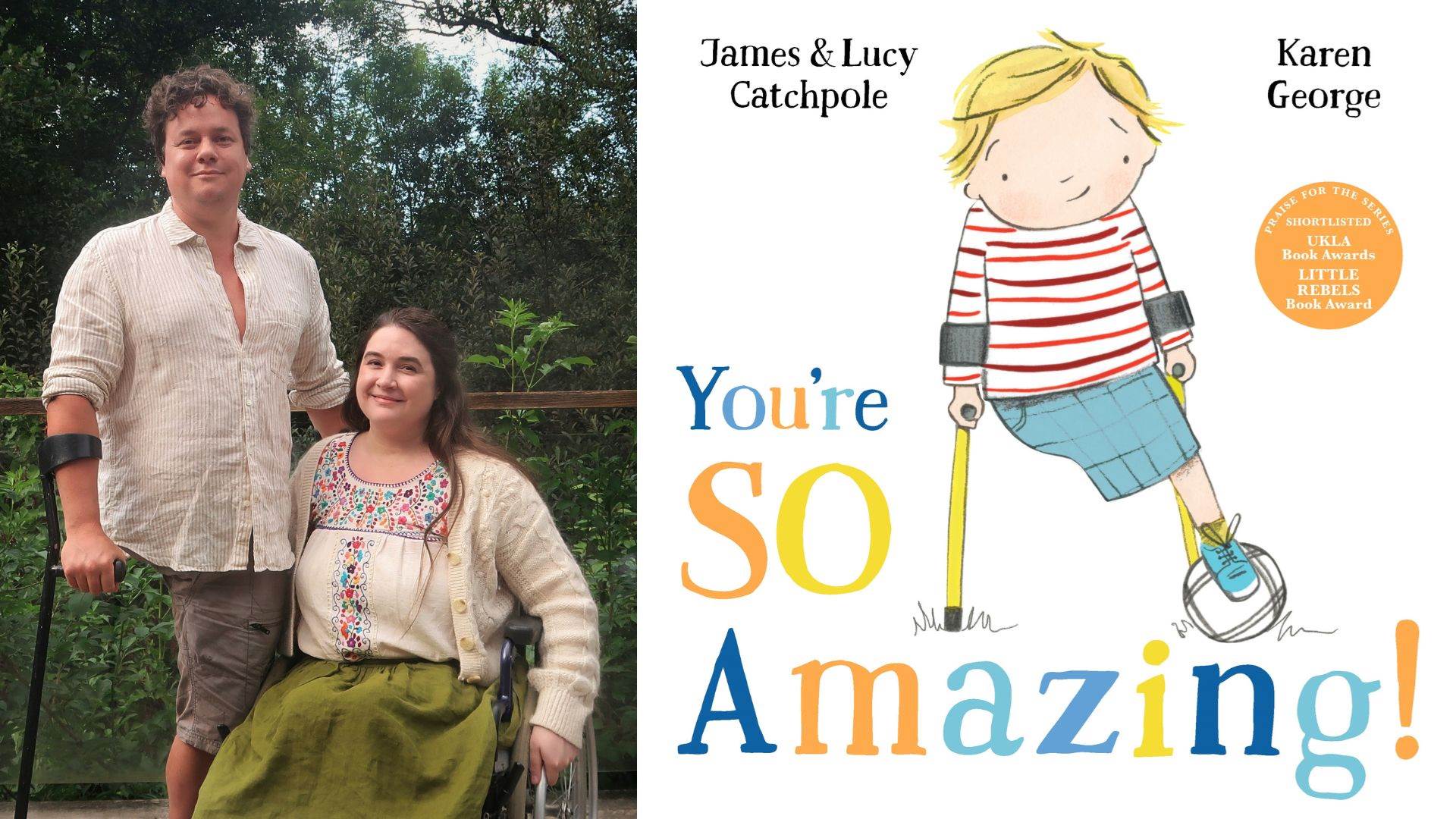

James and Lucy Catchpole and the cover of You're So Amazing

James and Lucy Catchpole and the cover of You're So Amazing

Telling the truth about disability

Truthful portrayals of disability in fiction are few and far between. Writing truthfully about disability is hard, and to be fair, historically most writers haven’t tried. I mean, quite a few writers have written about disability (and some pretty good ones, too: Sophocles, Shakespeare, Dickens…) but writing about it truthfully was never their aim. Tiresias the Blind Seer, Richard the Third and Tiny Tim are deeply powerful characters, but it’s hard to make a case that they have much to say about any kind of disabled reality.

Those writers tap into narratives and feelings commonly associated with disability – the blind man has second sight; the deformed man is evil; the crippled child is cheerfully pitiable – so as to make their stories more compelling.

In storytelling, disability can be a highly effective device.

On the other hand, the history of children’s literature is a comparatively modern one. You might think, then, that children’s authors will have approached disability from a more enlightened perspective. Well, maybe the best we can say is that at least they’ve tried. Or just: some are trying. Any ill or disabled person who has ever been subjected to the special hostility society reserves for those suspected of faking illness will recognise the active harm that the portrayals of ill and disabled characters in Heidi and The Secret Garden can cause. If a breath of fresh air and a little encouragement is all it takes to cure the lame, then pushing their wheelchair down a mountain is almost a kindness, after all.

But perhaps that’s unfair. Heidi may still be read now, but it was published only ten years after the death of Charles Dickens – it’s hardly modern. What of the more recent canon?

Well, I’d argue that Richard, Tiresias and Tiny Tim still cast a long shadow.

Illustration: Erika Meza

Illustration: Erika Meza

'Soaked in the tropes'

Of those three, deformity as a mark of evil – outer deformity as a manifestation of inner deformity – is perhaps the trope you’re least likely to encounter in recent children’s books. But still, you don’t have to go back far to find it. Voldemort will haunt us forever. And Roald Dahl even spells out the theory for his young readers in The Twits, albeit with some clever caveats: his horrible antiheroes have grown the faces they deserve, glass eyes and all. King Richard, eat your heart out.

Tiresias has a direct modern counterpart in Marvel’s Daredevil, the blind crimefighter, of course (Professor X is the wheelchair-using version). And this conceit spills over into children’s stories, where disabled-kids-as-superheroes with special powers to compensate for their limitations is a well-worn trope.

And Tiny Tim? The boy whose courage and generous spirit (whose ‘big heart’ we might say now) launched a thousand memes? Think of the most successful children’s novel about disability of the past eleven years and there he is – at least, for me – still cheerfully tugging on our heartstrings.

Because here’s the thing: writing truthfully about disability is hard, even if you know what you’re talking about. (And I would make the case that very few authors do.)

All of us – even disabled authors – are so soaked in the tropes, so immersed in the age-old narratives about disability, that it can take a conscious effort to purge them. My experience of trying to tell my own story of having been a disabled child, in What Happened to You? and now in You’re So Amazing!, was partly one of trying to see the traps and pitfalls so as to manoeuvre around them. In fact, my instinct was always to downplay my main character’s emotions – his frustration and sadness, especially – precisely because I could hear in my inner ear the sound of tiny violins, hovering like mosquitoes, just outside of the frame.

(If I’m honest, going by the cultural Pole Star for this sort of thing – the begging videos of Children In Need – then the true soundtrack of pity, of the child who can’t afford a new wheelchair, is really a haunting solo piano. The violins are more about inspiration. They come soaring in later, after the drum fill when the celebrity arrives with the new electric wheelchair we’ve all paid for.)

Writing stories that have never been heard before

One of the wonderful things about having an editor like Alice Swan at Faber and an illustrator like Karen George, and on the most recent book, a co-author in Lucy my wife (herself a wheelchair-user), is their capacity to see the places where I might have over-compensated in trying to sidestep a snare. It’s no coincidence that the real emotion in What Happened to You? comes in a wordless spread: I had very little to do with it! And the humiliating encounter between Joe and a character we like to call Annoying Dad in You’re So Amazing! may be drawn from scenes in my life, but my understanding of those scenes comes directly from a conversation Lucy and I have been having since our first date, nineteen years ago, when we started to talk about the strange and confusing ways the world responds to our respective disabilities.

In fact, I’d actually go as far as to say this: I’m not sure I’d ever have found the clarity of thinking to question all those false narratives around disability, had I not met Lucy. It took both of us to write You’re So Amazing! – but I’d never have written What Happened to You? either, had I not married another disabled person who could help me think all of this through, from the inside.

Small wonder then that non-disabled children’s authors, who write about disability with often the best of intentions, so often miss the mark in spectacular fashion.

And that’s why it’s so exciting that a new generation of disabled children’s writers is finally being discovered. In the long history of literature, they really do have the potential to write stories that have never been heard before.

You’re So Amazing! by James and Lucy Catchpole and illustrated by Karen George is out now, and is our Bookmark Book of the Month.

You might also like...

James Catchpole: What to do when a child asks someone about their disability

Topics: Bookmark, Disability, Inclusive, Features