Is there an age up to which happy endings are required?

Published on: 27 July 2015 Author: Jo Cobley

The brilliant award winning author and campaigner Sita Brahmachari, who's work includes the Red Leaves and Artichoke Hearts, became our twelfth Writer in Residence back in 2015. In this blog Sita and human rights educator Jo Cobley, discuss how to present difficult and brutal subjects in children's literature.

How young can you be to learn about Human Rights?

'It's my belief that education, and Human Rights education in particular is absolutely central to resolving the big questions that we are facing in the world today.'

Jo Cobley - Human Rights Educationalist.

I have a passion for human rights education and see that children's natural instinct is to want to stand up for what is 'fair' and to protest against the 'unjust.' This forms the spine of many stories for young people.

I was extremely proud when Amnesty International endorsed Red Leaves as a book that might help readers to empathise with characters and stories facing young people caught up in global crisis of destitution, both in this country and internationally - yet all my characters come together in a city wood, where the world of fables, reality and dreams merge.

'No outsider's ever going to understand our culture and religion. Innit? Muna was saying as Miss Sealy peered at them over her glasses.

'What have you two been whispering about? The librarian smiled warmly as the girls passed her desk on their way out.

'Nothing, miss!' Muna laughed 'Just talking about culture 'n' stuff!'

(Pg 77 From Red Leaves, Macmillan Children's Books)

Leaving the classroom and entering the imaginary world of the wood where past and present collide with dreams and imagination.... my story explores if Muna's comments can really be true?

I was sent this photo of a well-thumbed copy by a Librarian who said that the Somali girls in her school had been so happy to find 'Aisha's story in the pages of a contemporary fable and that the book had been a catalyst to talk about 'culture 'n' stuff'.

I want to share with you a conversation between myself and Jo Cobley - Human Rights Educationalist - who headed the Education and Student Team at Amnesty International for eight years. We have worked together with Jane Ray at The Islington Centre for Migrants and Refugees about which I have written previously on this blog.

Jo told me about an inspirational workshop she facilitated recently at a local school. I think that much of what she speaks is what children's authors also consider when writing stories which may be inspired by realities. There has been much talk in Children's publishing about whether stories that focus on 'the real world' and its big concerns are introduced to readers too young. These are things I think about as an author and also a parent of a ten year-old.

Are we spoiling children's innocence by introducing some truly harsh realities about our world in stories?

How are children mediating these stories through social media, radio, TV and news anyway?

For older readers Kevin Brook's Bunker Diaries was a controversial winner of the Carnegie Medal (2014) because his incredible story didn't have a hopeful ending.

In real life, stories often don't tie up as neatly or beautifully as they can do in children's fiction. Is there an age up to which happy endings are required?

As adults (In charge of libraries, publishing, buying, teaching from books) are we censoring and limiting children's experiences by assuming that they can't or shouldn't be able to cope with some difficult and unresolved problems that we face in the world today?

If my child character is a refugee, like Aisha in Red Leaves and her world is harsh, full of conflict and injustice is it wrong to share her story with children who may not come from her world... but are children all the same... children who in reality may be class mates?

Should children be protected from the grim details of Malala's story?

What is the function of storytelling in our society?

These are big questions but they are ones that we authors ask all the time and I think they lie at the heart of writing diverse stories for the world we live in.

Noel Greig the late playwright and director was a great inspiration to me - he used to say 'when you walk into a classroom you meet thirty children and the world' I always keep that in mind when I write.

I am going to offer you a case study of the sessions that Jo Cobley offered to a London Primary school as an Amnesty International School Speaker, and leave it to you, the reader to decide who a story that might emerge from this work rooted in the present suffering of the journalist Raif Bidawi would be suitable for. Would it be appropriate for a ten year-old? It was for mine.

Jo Cobley, Human Rights Educationalist

'It's my belief that education, and Human Rights education in particular is absolutely central to resolving the big questions that we are facing in the world today.'

The sessions took place in a London primary school with Year 6 students and two highly experienced and knowledgeable teachers.

The classes had already worked on a cleverly planned Human Rights topic for six weeks. They had studied the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, learned about the Civil Rights Movement in the USA and they were also taking part in all the Amnesty Youth Awards, which allows young people to explore human rights themes and issues through journalism, photography, song-writing, campaigning and fundraising. My role was to introduce the children to a real Amnesty case happening now to bring their topic into the real world.

I've run many sessions with Years 5 and 6, and always discuss the plan and material with the class teacher first. I started the session by introducing Amnesty, the symbolism of the candle with barbed wire around it, and the Chinese proverb:

'It's better to light a candle than to curse the darkness'.

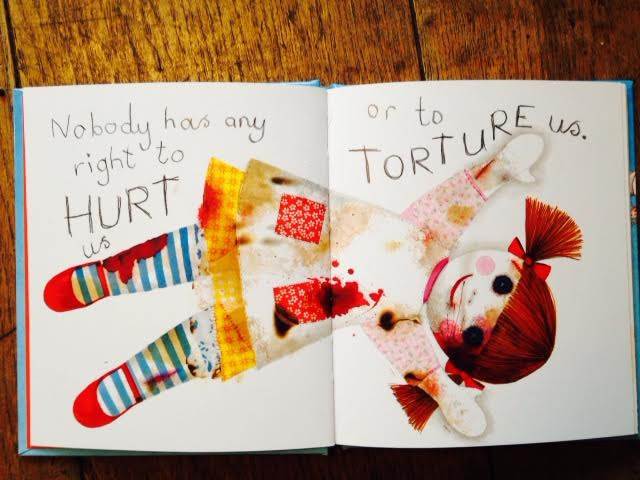

Holding up the image by Children's Laureate Chris Riddell in from 'Dreams of Freedom' In words and Pictures (Published by Frances Lincoln Books)

Children like the slogan because it's empowering to think that when you see something is wrong you should try to do something to change it. I explained the case we were going to look at focussed on the right to freedom of expression, and the right not to be tortured or subjected to cruel or inhuman treatment. The children had explored these rights previously and I were extremely impressed by their knowledge and level of understanding.

We then spoke about things that we like and don't like. We talked about pop bands and football teams, and of course likes and dislikes differed greatly. So, we discussed how we express that and if we should be free to give our opinion, and if we are free how do we communicate our difference of opinion. We discussed that there are limits to freedom of expression and that in very limited circumstances governments have an obligation to prohibit hate speech and to protect the rights and reputations of others. We then talked about how the young people chose to express themselves through art, fashion, photography and music and what it means to be free to do so.

The conversation was just after the Charlie Hebdo murders, which many of the children had heard about, and prompted a very intelligent and measured discussion around freedom of expression and its limits. They didn't all have the same views, and they're a diverse group, but they were able to articulate their different ideas, and respect each other's opinions.

I then introduced the case study of Raif Bidawi who is imprisoned In Saudi Arabia for exercising his freedom of expression. He set up a website where he imagined social and political issues would be debated. He wrote a blog in which he was accused of ridiculing the religious police and failing to remove 'offensive' content of other contributors, and was sentenced to 10 years in prison and 1000 lashes.

I chose this case study partly because I believed that the international pressure to release him, a prisoner of conscience and victim of such cruel and inhuman treatment, was so great that it would be effective and that the children, having worked on the case, would see that their activism and efforts had contributed to his release. To date it proves not to be so.

We looked closely at the story of Raif and his family life - he is married with three children - and life in Saudi Arabia. We looked up where it is on the map of the world. The children had been studying Islam the term before. We talked about the fact that Raif was imprisoned and what he is accused of.

At each stage, I impressed on the group that Raif is a real person with a family who love him, and who enjoyed lots of things that we'd all enjoy too. However, although I told the children about the lashes, I did not dwell on the detail of his cruel treatment and I was careful to use language which was appropriate and understandable to the age range. The group wrote simple, beautiful messages to Raif to give him hope, encouragement and to let him know they were asking for him to be released. The teachers and I then worked with these wishes to write a communally authored letter to the Saudi authorities.

Amnesty were moved by the responses of young people and the letter was sent. To date Raif Bidawi is still in prison.

Image by Jane Ray from 'We Are All Born Free' The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in pictures - Frances Lincoln Children's Books In Association with Amnesty International.

So far there is no happy ending for the young people to see as a result of their discussion, their action and deep empathy

Does that mean that they should never have been involved in this project?

In Red Leaves I couldn't bring Aisha's father back to life, but I could make my character Iona empathise with her, step into her shoes and understand something about her world. Plotting a future for these characters beyond my story I could imagine that these two young women may well stand together in the future and be changed by what they have discovered.

Students at the school entered work into Amnesty Youth Awards and received commendations and prizes in photography, journalism and song writing... might that experience also impact on theirs and many other people's futures?

Reverting back to reality I do believe that the project Jo Cobley describes may have an equally strong impact on the young people with whom she works. Many believe that the act of standing up and taking action is empowering and motivating for young people, and in this increasingly complex world helps them to feel their agency, even if the results are not immediate... the common thread of her work in education and the work of authors is empathy.

Topics: Writer in Residence, Features

Add a comment