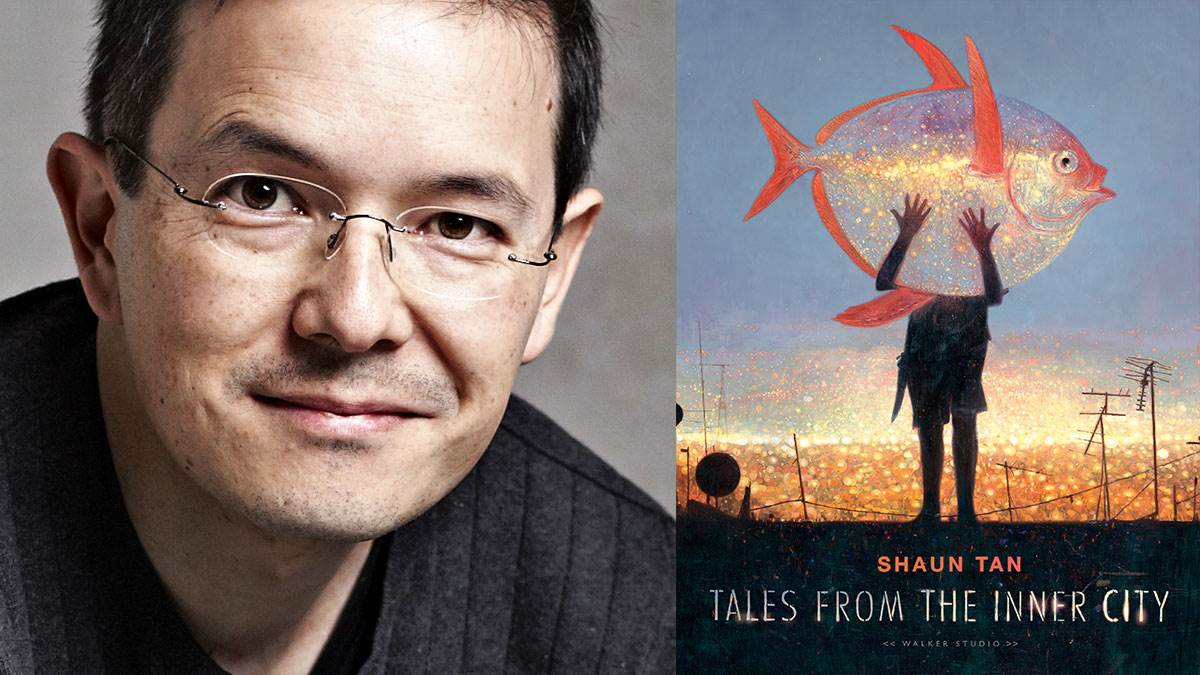

"A whale in the sky": Shaun Tan on Tales from the Inner City and winning the Kate Greenaway Medal

Published on: 22 Mehefin 2020

Shaun Tan's beautiful picture book for older children, Tales from the Inner City, won the Kate Greenaway medal for illustration earlier this year. He talks to us about winning the prize, his own favourite books, and the magic of a frog in a boardroom.

Congratulations on winning the Kate Greenaway medal for Tales from the Inner City! How does it feel to have won such a famous illustration prize?

Very exciting. I think the main feeling is of camaraderie with other writers and illustrators that have won the same award, especially over such a long history, that really is such a wonderful feeling. It’s such a fantastic arts community, book illustration, one with good integrity and of such great profound cultural value when you think about the impact on young, critical minds. Winning an award like this is something I could never have imagined when I started out as an illustrator, much less as a child noticing medal stickers on certain books, and reading them to try and figure out what made them special. I’m sure awards like this do encourage kids to read, and to read far beyond award-winning titles too.

Tell us a bit about how you came to create Tales from the Inner City?

It was an accumulation of many small creative acts over a long period, maybe stretching over the past decade, which is reflected in the anthology structure of the volume. I like to let things evolve organically in sketchbooks rather than pick or push a theme, only because I find that the latter never works! Interestingly, I always need to start with quite concrete images that are also mysterious, before I find the road to any sort of meaning: frogs on a boardroom table, a whale in the sky, a massive cloud of butterflies flooding a central financial district. What does it all mean? I’ve learned not to ask that too much, to just let myself daydream through notes and doodles in cheap, unimportant sketchbooks.

In the case of this book, I went over a mass of this material and noticed connections, such as a preoccupation with animals, and especially animals turning up uninvited in urban spaces. I realised later that this had something to do with my own anxiety about living in an inner city suburb, within a somewhat abstracted and artificial bubble, while the natural world was slowly collapsing somewhere else. I think we all know this feeling, and some kind of deep longing for a closer connection to nature, even as we also dream of exceeding it in a post-industrial world, such is our conditioning.

I thought a great deal about the world of our distant ancestors, and what they would think of the way we live now.

I was also visiting Melbourne Zoo and Melbourne Museum a lot, both not very far from our home, with our daughter who was a toddler while I was working on Tales from the Inner City. I became interested in her understanding of animals, her natural tendency to see the connection between herself and monkeys, lizards, wombats, everything, rather than as separate beings, We see this a lot in children’s literature too. Why are there so many animal stories? Particularly African megafauna - elephants, giraffes, lions. I can’t help feeling it has something to do with some deep memory of more cyclical, grounded times. Anyway, these are some of the ideas that drove me to create this book.

Illustration: Shaun Tan

You’ve won the prize in one of the strangest times in our history, in the middle of a pandemic where in many cities, as humans were made to stay in their houses, animals started to wander into people’s territory and people have had more of a chance to observe nature. Your book deals with similar themes of animals in the city - has anything that’s happened recently surprised you or did you see it all coming?

Yes, I did try to warn you all through illustrated literature! Not really. I do see other things coming though. When the pandemic hit, my first thought was actually that this might be a dress rehearsal for something else, something much worse, especially as it just came on the heels of devastating bushfires here in Australia. It’s a kind reckoning of material reality, our dependence on nature and biology, against the artificial fictions that prop up stock markets, political agency, human supremacy and other deep mythologies. I mean, you can see how poorly those governments based on fiction and blind opportunism are failing to handle the pandemic.

Any physical crisis is a reality check I suppose, because we do – and I certainly include myself here – have a tendency to waltz along half-asleep as if we are not heading toward a precipice, even when the facts are staring us in the face. I would say that art and literature is another kind of delusion, but one that can also be positive, in steering us back to thoughtful consideration of all those anxieties we tend to put away for tax-time. It’s a place of reckoning.

To answer your question more properly, I was influenced by a several science books I read while working on Tales from the Inner City, particularly Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari, and The World Without Us by Alan Weisman. Both discuss the bigger picture of our relationship to nature, and possible futures, the latter about what would happen if humans suddenly vanished. The basic consensus is that nature would very quickly take over, much faster than you’d expect.

Not far into the lockdown, I did see an owl sitting on an electrical wire in the evening, something I’d never seen before so close to home; it was like a little reminder of what things will outlast us, should they manage to survive us.

In Tales from the Inner City, office managers turn into frogs but actually like their new lives! How much can books shine a light on different ways to live and new realities?

Oh, perhaps more than any other media really. Fictional stories are nothing if not attempts at empathy, of practising our imagination in different contexts, and having the space to do so with one’s own interpretation, life experience and time. Of course, it always depends on the reader and how receptive they are to considering other ways of being, other possible worlds we could be inhabiting, though I think people do come to books precisely with this curiosity. To painting also, both are slow media that thrive on self-reflection.

Illustration: Shaun Tan

Which books made you think when you were a child, and which children’s books make you think now that you’d like to recommend to us?

As a child, lots, but the one that comes most readily to mind is George Orwell’s Animal Farm, which I mentioned in my Kate Greenaway acceptance, mainly due to the link between that early experience – arguably too early, as my mother read it to me by accident at bedtime, not knowing the background – and my penchant for abstracted animal fables. I do think Animal Farm works quite well as a children’s book, even though that may not have been Orwell’s intention at all, as the basic themes resonate beyond satire. As a kid going to school, I understood a bit about power and bullying, about arbitrary rules, lies and even brainwashing, so I could relate, even though my knowledge of Soviet history was non-existent. The other fiction that left a strong impression on later childhood, around 11, a very impressionable age, were the stories of Ray Bradbury. Not exactly children’s literature, but not excluding childhood imagination either, quite a good bridge into adult themes actually. They had a special power to them, even though I didn’t understand them very well at first, and I think that influence comes through in Tales from the Inner City, I know some readers have mentioned it.

Children’s books now that make me think? I’ve been looking at old and new books with my daughter, just turned 7. One that stuck out particularly for reasons I’m not sure about is Little Fur Family by Margaret Wise Brown and Garth Williams. Not exactly new (1946) but I’d not seen it before, and it has a strange kind of joy and sweet sadness to it that I can’t explain. I’ve enjoyed the work of Sydney Smith lately, just looking at Small in the City, and Belgian author and illustration Kitty Crowther, who I’d love to see translated more into English. Lately our bedtime reading has been Beverly Cleary’s Ramona novels, which my daughter likes. Beverly Cleary, now 104 we notice, is very good at showing how well children must often hide their true feelings and intentions from adults who simply wouldn’t understand. Good children’s writers really nail it when it comes to knowing that strange inner world.

What is your favourite animal to draw?

Ha, that’s such a good question but I haven’t heard it for decades! My first thought is a fish because it’s pretty easy and nobody knows so much if you get it wrong. But looking over sketchbooks, it would have to be birds, an animal I always come back to. I’m not a birdwatcher but could imagine being one, they do seem somehow very transcendental, just amazing creatures. All animals are endlessly interesting, even those most likely dismissed, but there’s something about the long lineage of birds, going back to dinosaurs, that gives them a special presence on earth. The lengths they go to for seasonal migration for instance, is just staggering. And we humans complain about long haul flights from Australia. Well, used to complain!

Illustration: Shaun Tan

Your book Tales from the Inner City is aimed at older children. Why do you think picture books for older children are relatively rare and is that a problem?

I think it’s just a cultural thing, and the short answer about rarity is I don’t know. Animation, the close cousin of picture books, is certainly as comfortable with older audiences as it is with younger ones. Music videos, which I see as almost moving picture book texts in terms of visual-verbal play and brevity, show the broad range and possible audience for poetic visual illustration about the length of a song. Painting exhibitions, usually having the same image count as a picture book, also usually embrace all generations. And in somewhere like Japan, the variety of illustrated literature for youth is mind boggling. I think it’s just a convention that we’ve gotten used to, that picture books are so great for younger kids, especially learning literacy and basic looking skills, that it’s become a comfortable identity.

But obviously older kids are still interested in images, reading, and like short, smart stories, I know I certainly did. I first started working with Gary Crew, a versatile picture book creator and literature academic, and that was always his question, why not illustrated books for older readers? In Australia there was a big movement for that in the mid-90’s and I was fortunate to start working then. Only later did I realise this was quite unusual in places like the US and UK. But I think that’s gradually changing, especially as the gap between comics and picture books often get muddled, which I think is good, and there’s a lot more stylistic experimentation going on.

You’re the first illustrator of colour to win the Kate Greenaway. What do you think is the key to make sure many others follow in your footsteps?

It’s a question I find tricky to answer, because I’ve not considered identifying with that label until it was mentioned in relation to the Kate Greenaway actually, but also happy to take it on. My father is Chinese, my mother is Australian of Anglo-Irish background, and I grew up in a very Anglo-Australian suburb, adopting all those mannerisms and cultural references. But I did experience racism, and that’s probably had some affect on my empathy with minority and marginalised groups, and I grew up feeling different, sometimes a bit rootless, but that may not be uncommon for many Australians, regardless of background. I do notice that Chinese Australians pay a great deal of attention to what other Chinese Australians achieve, especially in the arts where previously that was a bit unusual.

I’d like to think that it helps some kids who are bit insecure about their ethnic background, or perhaps having trouble convincing conservative Asian parents (a subset only, but clearly one with some authority) that a career in the arts can be a good one, to be encouraged by the example of Asians winning awards in fields where that may not have happened previously.

Find out more about the Kate Greenaway medal

Read about the books entered for this year's Kate Greenaway medal.

Topics: Picture book, Animals, Environment, Nature, Features