How to read comics: a beginner's guide

Published on: 8 Gorffennaf 2012 Author: Hannah Berry

The fantastic graphic novelist Hannah Berry, who's work includes Adamtine and Brighten & Brulightly, became our seventh Writer in Residence back in 2012. In this blog Hannah wrote about getting in to comics, the many ways a comic books pages can be laid out and why they're a fantastic medium for engaging story-telling.

Take a look around you. Look at the person to your left. Look at the person to your right. There is a high probability that some or all of these people are comics illiterate.

Comics illiteracy is a fact of life: it will hold back many from enjoying comics and graphic novels and may have nothing at all to do with regular literacy skills.

If you yourself don't know how to read a comic, do not be ashamed. You're not alone! Most of my family couldn't read comics before I went and wrote a graphic novel and they had to suffer the obligation of reading it. A good friend and mentor, a prolific professional writer, admitted he had no idea how to read my first book when I gave it to him. They can appear overwhelming to the uninitiated (much like regular novels, in fact).

A common tactic is to read all the text - because that surely contains the serious and pertinent information - and then go back and look at the pictures, which are all just decoration anyway. It makes perfect sense if you're unfamiliar with the medium. Important details, then pretty pictures. To do otherwise seems like mashing your dessert into your main. Yet this is exactly what needs to be done: the text and the image need to be absorbed at the same time. You need to load up that fork with lasagne and ice cream and chow down on the resultant mystery within.

A bemused lady in a Marks & Spencer suit once asked a panel I was on at a literary festival 'What is the point of having pictures in a graphic novel when you can just write it?' And I'm glad she asked, because I can tell you why right now.

The words in a comic, the dialogue or the narrative, tell you one thing, the images tell you something else. The Golden Rule of Comicking is that you should never needlessly repeat things, for example, drawing a person looking sad and then adding a speech bubble saying "I feel sad". It's superfluous. It's naff. It condescends the reader. If you, as a reader, find yourself being condescended in this manner, you have my permission to cast into a nearby fire or pit whatever you are reading and label it as a Bad Comic.

The point is that by combining the text and the image you can say so much more, much more succinctly and elegantly than with either of the two alone.

Easy to decipher, yet subtle as a gnat at the door. A way of giving content that's expedient while simultaneously rich in information.

Looking at the page of a graphic novel or comic can be overwhelming to a beginner, just as looking at a page of text can be alarming to someone learning to read. It can seem like a ridiculous amount of information to absorb. But although it may look wild and disordered, a page in the comic format is just as strictly laid out as a page of text. Your eye may flit around the page initially like a bird trapped in a room (known as 'panoptic reading', I believe), but you just need to learn to take in the information slowly, piece at a time.

Start as you would normally - at the top left (unless you are reading manga which, like Japanese writing, starts at the top right...but lets not over-complicate things). That first box (or 'panel' if you will) in the top left containing the text and image, you need to think of that as one of these forkfuls of lasagne ice cream. Take it in; savour it; digest it. It's a slice of time, to be mulled over in as much or as little time as you need. Then, keeping that in mind, move to the next panel. Just like prose, the meaning and therefore the context builds up. The only difference is that a large part of the information is visual.

And that's really all there is to it.

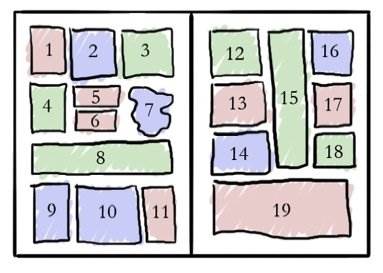

The panel order can sometimes be tricky to become accustomed to but, just like everything else, there are rules. Just remember that panel transitions can never, unless otherwise instructed, go from right to left unless starting a new row, and so you need to read the panels in the order that prevents this. Like so:

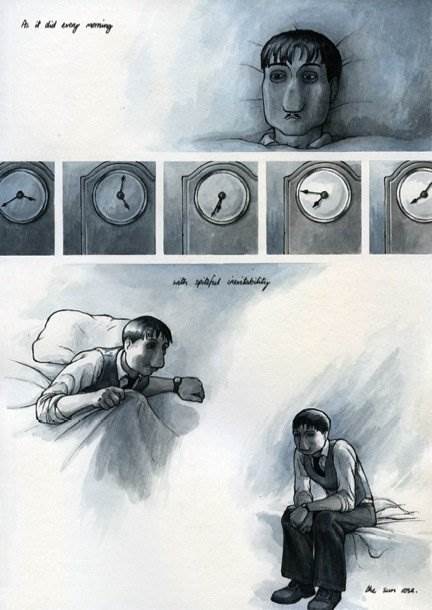

Occasionally you'll come across a page, like the one below, which hasn't used formal panels. In that case, imagine you're dragging a ruler down the page (if funds will allow you may use a real ruler) stopping after each element and reading left to right as you do so.

(This is the first page of Britten & Brülightly - I'm a little shaky on the copyright issues when using images on a blog, but I'm pretty sure I won't get into a fight with the artist over this.)

There is also the question of time. Comics may only have two dimensions, but they can also dabble in time. As you move from one panel to the next, time passes along with it, and you should get a sense of this from the imagery or the text or both. (When creating a comic, the power of suggestion at your fingertips is immense, and the urge to leap onto a desk yelling I'M A TIMELORD is sometimes quite strong.)

Also worth noting is the fact that, in comics, everything means something. Everything.

If you look at the layout or the composition of different elements or the way the writing is on the page, you can glean subtle levels of meaning around the content. For example, if the layout suddenly becomes non-linear, it's suggesting that the story has become non-linear also. On the page above, I've used formal panels to denote the regular passage of time against the drifting actions of the character. These are the very basics, but for more info on the technical breakdown and capabilities of comics, I'd recommend looking up the work of the brilliant Scott McCloud, particularly Understanding Comics.

Talking of literacy, it's interesting that the lasagne-and-ice-cream mashing comes a lot easier to those who are already occupied with the mammoth task of learning how to read, from young children to adults who have been left behind. The reason for this is precisely because they don't have the same reliance on text that confident readers do. When learning to walk, you look around for supportive objects to help you; when learning to read, the supportive objects are pictures.

Everyone can read images: they are universally decipherable in varying degrees of clarity. Symbols and images can be interpreted from a very young age and are the bedrock of visual understanding before the written language, so it makes sense that they can be trusted. When you learn to read, you lose your reliance on image, and I've found that the longer it's been since a person read a picture book - ANY picture book - the harder they will find it to move some of that reliance from the text to the image. This is why people find the idea comics so childish: because it feels like regressing. In fact, it's just dusting off an old skill.

It really is an incredibly accessible way to encourage literacy, both the visual kind and the traditional kind. I'm currently using French graphic novels to practise my meagre French language skills. And you know what? J'y prends plaisir.

The thing people don't often realise is that comics and graphic novels don't have to be simple: increase the complexity of the text, image and subject matter and the reading age increases along with it. There's no reason why age-appropriate comics can't be used in schools as a reading aid, for children to grow up reading them and then continue to enjoy them all throughout life.

Dear god...that's why BookTrust asked me to do this blog! They only wanted me for my medium's accessibility! The cads.

Topics: Graphic novel, Writer in Residence, Features

Add a comment