Making Mischief: using poetry in the classroom

Published on: 27 July 2023

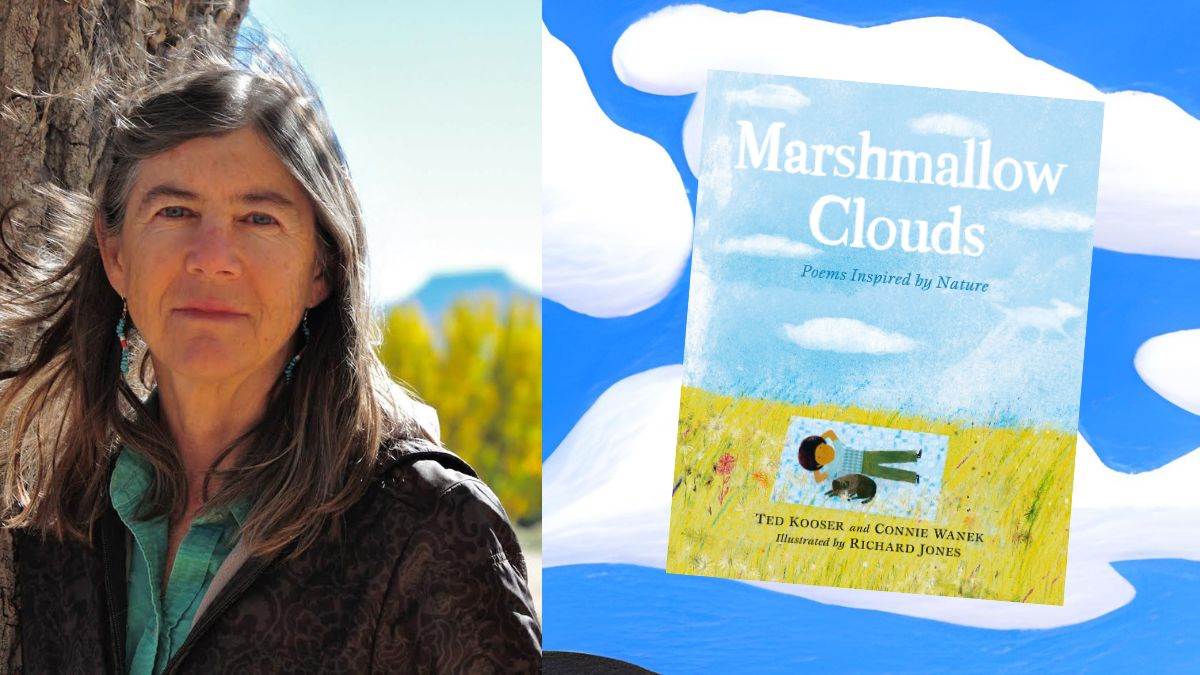

Poet Connie Wanek suggests some ways to stimulate children’s imaginations using poems

As we grow up, most of us learn to be ‘serious’ and ‘realistic’, and there’s nothing wrong with that. We may, at some point, be advised by our elders not to ‘let our imaginations run away with us’.

But that is exactly what writers do when they write fiction and poetry. It’s how we tell stories. It comes very naturally to most children, and we writers believe the imagination is also an important component of developing, for instance, empathy. ‘What if I were the new kid and I didn’t know anyone at school?’ ‘What if that was me, in a wheelchair?’

Poetry can be a genuine tool in the human workshop. We reach for poetry when we’re very sad, seeking consolation from words people have found to express grief.

Often we try to compose our own poems, as well, during hard times. Conversely, when we are in the presence of something grand or utterly beautiful, we appreciate those who have somehow found the words to express awe, or even simple contentment. Poetry seems a conduit for feelings, as copper wire carries electricity.

In the afterword of Marshmallow Clouds, Ted Kooser and I offer the notion that using our imagination is also a kind of play. I’m not a teacher by profession, but over the years I have gone into many classrooms to read poetry to children and to help them write their own, and most of them relish the invitation to create ‘imaginary gardens with real toads in them’, as Marianne Moore phrased it.

In that spirit, I’d like to offer a few ideas about how to encourage children to, as Ted says,

‘keep your imagination healthy and happy’.

One idea I have used in the classroom, which seems to appeal to a broad range of ages, is this: Let’s imagine that recently you finally met your identical twin. How is it you never knew you had one?

There’ll be ways this person is exactly like you, and ways she or he is different.

Kids can talk more freely about who they are and how they feel, sometimes, by ascribing these things to a twin, an ‘other’.

You can combine this idea with one of the most fundamental elements of good writing, which is the use of the senses. Perhaps this twin doesn’t dress the same (sight), and she has a different accent because she was raised in Canada (by wolves?). That’s sound. Maybe all she does is howl! And taste: she doesn’t like strawberries, if you can believe it. What’s that smell? Onions? Oh, and something else. Your twin smells like the forest, like wild mushrooms and like a waterfall. You reach out to touch her shoulder, maybe to lead her over to the playground, and she takes your hand, and squeezes hard. Look, a tear. You didn’t know about her, but she knew about you, and she has long dreamed of the moment you would meet. ‘It’s you at last.’

Another path into the forest of poetry is reflected in Marshmallow Clouds. The book is arranged in four sections corresponding to the four elements: fire, air, water, and earth. Each of these elements is deeply suggestive, I find, and can be used individually as in: ‘Today we are going to write something about fire.’ Think about a story that has fire in it (personally, my mind is instantly directed to the time my brother accidentally set our barn on fire). Perhaps you have a dog that is very small, but very excitable, maybe a furry dog that sits next to you on the couch and keeps you warm. Maybe the fire is in the dog’s eyes. Maybe you have a fire pit in the yard, and it draws the family together. And in the presence of fire, someone begins to tell a story.

Four elements; four poems, perhaps. And…what if there was a fifth element?

What would that be?

I’d like to say also that the marvellous paintings by Richard Jones in Marshmallow Clouds illustrate the cross-pollination of the arts. While in this case Mr Jones used the words of the poems to create truly marvellous visual images, equally fruitful is to introduce a painting to children and have them write about it. Think of Vermeer’s “Woman Reading a Letter.”

Imagine a writing session exploring the mysteries contained in that painting!

Finally, Ted and I both love figurative language, simile, metaphor. For us, it’s tremendous fun to come up with apt and novel similes and see where they lead. An overturned boat ‘looks like a hand cupped over a shadow/to keep it from scuttling away’. Tadpoles resemble commas, ‘the liveliest of all punctuation’.

In my experience, children love to think up similes. Recently I visited my granddaughter’s second grade class and I brought along a walnut shell I’d found in the garden, nibbled empty by a squirrel. We passed it around. “What does this remind you of?” I asked, and the answers came excitedly: a heart, a skull, a mask. And more. ‘It makes me think of hunger.’

These are a few ideas to help children retain some of their natural openness and wonder at the world, through language. The writer E. B. White once said,

“All I hope to say in books, all I ever hope to say, is that I love the world.”

Marshmallow Clouds by Connie Wanek and Ted Kooser, illustrated by Richard Jones and winner of the 2023 CLiPPA Poetry Award, is available now.

Topics: Features