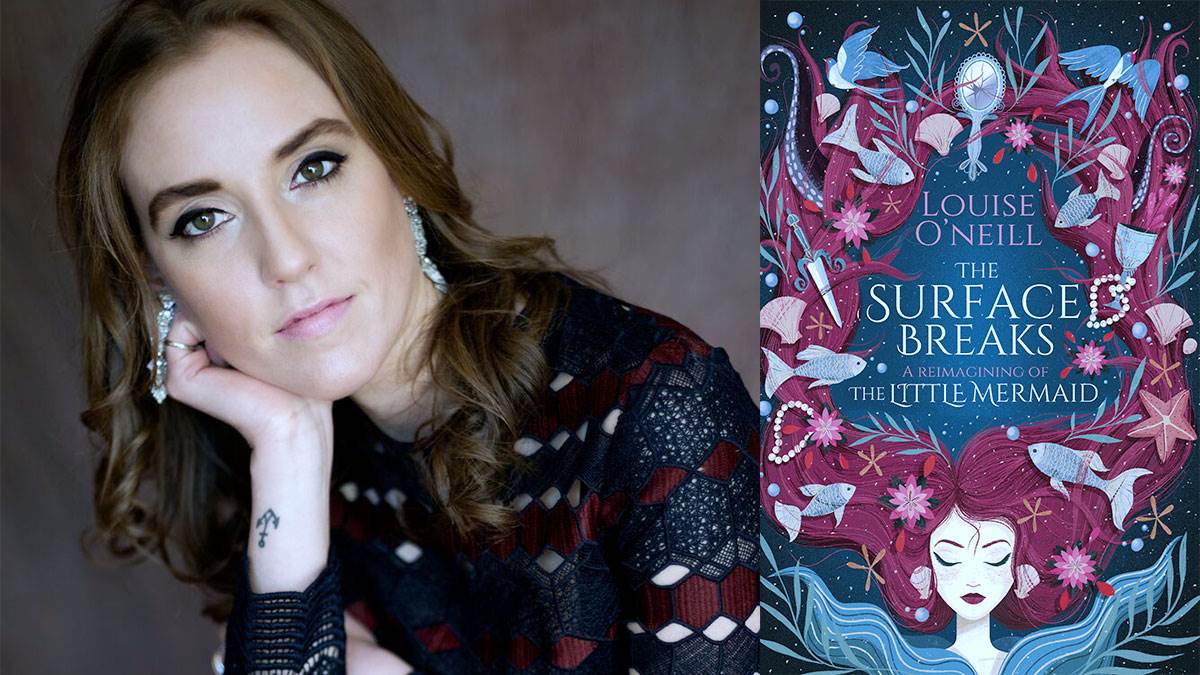

Louise O’Neill: 'I’m writing the books I needed to read when I was younger'

Published on: 30 May 2018 Author: Anna McKerrow

Louise O’Neill talks to us about her new book, The Surface Breaks: a feminist re-imagining of The Little Mermaid and the (sometimes negative) power of fairy tales.

The Surface Breaks is a feminist reimagining of The Little Mermaid. What made you want to retell that fairy tale in particular?

I loved The Little Mermaid story as a kid, and I really loved the sea. For the first four years of my life, we lived in a house at the edge of Inchydoney beach in Ireland, and my sister and I spent all our time racing around the sand dunes, swimming, having to be hauled in, blue-lipped from the cold at the end of the day.

My mum said that when I was really little, if I was ill or upset, the only thing that could soothe me was putting me in the bath. I had that natural affinity for water even then. And then, when I was four, Disney’s The Little Mermaid came out. Not only was I fascinated by the sea, it was the first new Disney princess for 30 years and branding and marketing really made it huge. I think that story, as represented by Disney, imprinted itself on a generation of young women.

What elements does The Little Mermaid have that you felt you could – or should – tell differently?

The Little Mermaid mutilates her body so that a man she barely knows will find her attractive; having been a teenager who was struggling with disordered eating, I really started wondering how that messaging had had an impact on me as a young child.

When I went back to the original fairy tale, I was shocked by it; how the Little Mermaid has to exchange her voice for legs, and how when she asks the Sea Witch, 'how will I make him fall in love with me?', the witch tells her, 'you still have your lovely form'.

And there’s the violence of the story – the incredible pain that the mermaid has to suffer for being a woman. My dad, after reading The Surface Breaks, kept asking me – is this bit in the original, or is that you making that bit up? He was really shocked about what was in that original tale.

I really loved The Little Mermaid as a teenager, and then I was really ashamed of loving her after I found out how messed up a lot of the messages were in that story. So there was a part of me that wanted to reclaim her, so that she wouldn’t be a passive victim: that she could be a girl, one who wanted to take up more space in the world and not less.

Sometimes I feel that I’m writing the books I needed to read when I was younger. I needed to read Almost Love, my adult novel, at 20; I needed to read Asking For It at around 17, and I think I needed to read this book, The Surface Breaks, around 13 or 14.

The Little Mermaid, illustrated by Dorothy Lathrop, 1939

The Little Mermaid, illustrated by Dorothy Lathrop, 1939

You grew up near the sea in Ireland and have a deep affinity for the ocean. Is there a power in the natural elements that you wanted to write about? Is connecting to that power empowering for children and teens?

I think there’s a lot to be said about growing up in the country or near the sea, having a strong connection to nature. My dad had also been brought up near Inchydoney and he always taught us to respect nature, he was very into environmentalism. When you live close to nature, you notice its rhythms, you notice the seasons passing more than when you do when you live in the city. And I now find that I need the quiet of nature. I draw my creative power from that quiet, being near the sea, being outside; I’ve got a busy mind, and it gives me the space and stillness I need.

John Moriarty, who was an Irish philosopher, said it best: the wildness in me needs to see the wildness in nature in order to survive. So, yes, I do think there’s an empowering message for young people there too about connecting to nature, to the elemental parts of ourselves. Having time to ourselves away from screens and social media, and letting it help put our problems in perspective.

How do you think stories like The Little Mermaid affected you, growing up?

I do wonder about the implications of fairy tales, but also Disney films, Barbies, Sweet Valley High. The obsession with beauty and thinness, and the correlation between beauty and goodness. If I hadn’t been exposed to that messaging, would it have impacted me anyway? Maybe. I don’t know. But it was very strong messaging to receive at such a young and impressionable age. In The Little Mermaid, the Sea Witch is depicted as a fat and unattractive character, but I wanted to reclaim that; my Sea Witch fully inhabits her body in a way I think is really important.

The Little Mermaid, illustrated by Ivan Bilibin, 1937

The Little Mermaid, illustrated by Ivan Bilibin, 1937

When I was a bit older, I was also obsessed with the Sweet Valley High and the Baby-Sitters Club series. My mum really hated Sweet Valley High – she was right, of course! Those books are so toxic – all the characters are blonde white girls, there’s no diversity, there’s terrible messages there about weight and dieting.

Mum was an English teacher and out of the three books we were allowed to take out from the library every week, she insisted that one had to be a classic – Treasure Island, A Little Princess, books she felt were important for me to read. And I’m really grateful to her for that.

What are your favourite fairy tale-themed books for children?

I was a big fan of Narnia, so that kind of fantasy has a lot of quite mythic elements in it. The Wizard of Oz, also, which has characters that feel like archetypes in it. I loved Philip Pullman and Judy Blume. The Hazel Wood, though it’s a YA read, was fascinating and really fairy tale-themed. I really liked also Sophie Anderson’s The House With Chicken Legs, which is inspired by the Baba Yaga myth.

Why do you think fairy tales endure?

I think, rather like Shakespeare’s plays, fairytales contain archetypes that people recognise. And there’s a chance for children to confront fear, loss and danger in a reasonably safe environment in the space of a fairy tale.

Also, it’s tradition. If you were read fairy tales as a child, you’ll probably share them with your children. They’re considered “classics”. And people are retelling them because they know them so well. They’re deep, familiar stories for many people.

Unfortunately, around those early folk tales, a lot of misogynistic meanings have been added; the gender politics in fairy tales is disheartening to say the least. They’re very didactic; there’s a lot of moralising and preaching in them, especially about beauty and purity.

I think there’s definitely a temptation for writers faced with fairy tales to think, maybe I’ll take out a lot of that toxic stuff and put in some subliminal messages about believing in yourself in there instead. To help young women reject the beauty myth.

So that they know from a young age, as my character Ceto says, that the most powerful and important thing a woman can do is live true to herself.

I’d like to think that my books can instil more positive messaging for children and young women. I want to create positive messaging for them, about their bodies, so that they don’t get programmed into body dysmorphia and thinking they’re not good enough.

Topics: 12+, Fairy tale, Features

Bookfinder

Find your next book

Use the Bookfinder to find the perfect book for you, your family and friends.

Twisted fairy tales

A booklist

Here's a list of some of our favourite twisted fairy tales - fun and anarchic new takes on traditional stories.

Celebrating inspirational women

Children's books that showcase the achievements of women

If you want to challenge gender stereotypes and show your little one some fantastic role models, then this is a good place to start.

Add a comment