Words for Silence: Finding our voice when words won't come

Published on: 02 August 2021 Author: Sam Thompson

Author Sam Thompson wanted to write a story for his son where speaking aloud wasn't the only way to communicate. In Wolfstongue, the power of speech is used by the foxes to keep the wolves enslaved - and it's up to a young character who struggles with his own words to help the wolves find their voice.

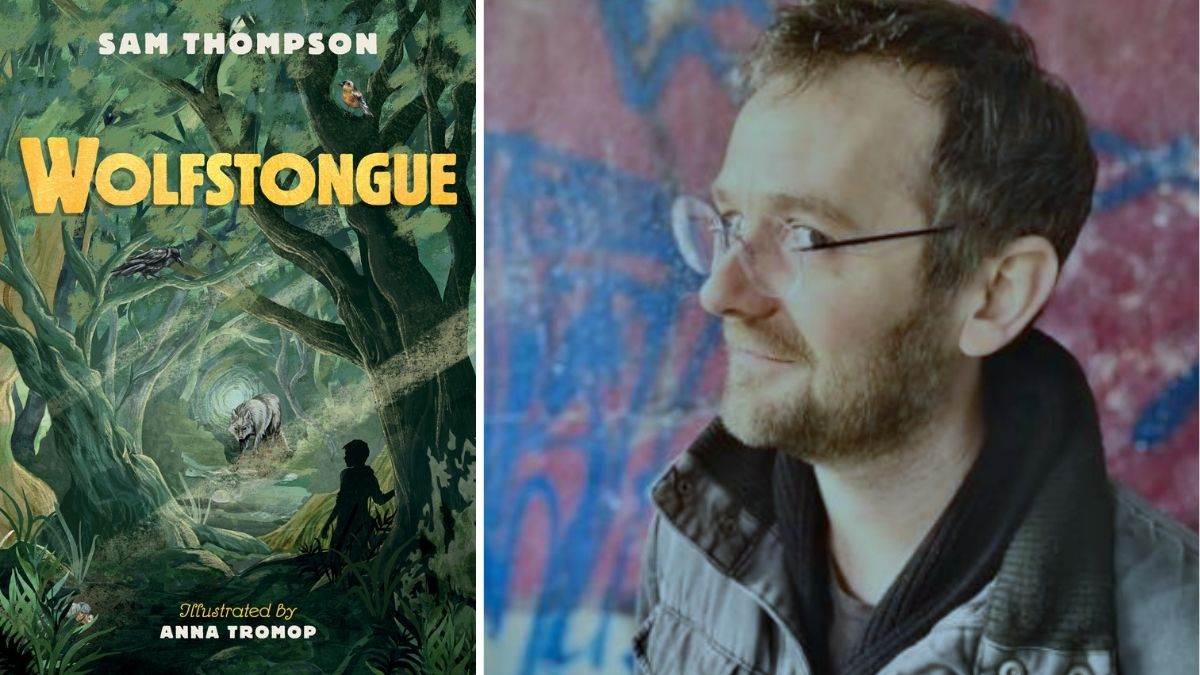

Author Sam Thompson and the cover of Wolfstongue

Author Sam Thompson and the cover of Wolfstongue

Wolfstongue is the story of a child who cannot find the words he needs. When Silas is with other people he is practically silent, but one day he makes friends with a wolf and discovers that there is a hidden world where animals speak.

I started making up this story for my younger son at a time when he was having trouble with his language. He loved wolves, too, and I had an inkling that there was a connection to be uncovered between wolves and words — that a tale about the silence of animals, and about the ancient fantasy that animals might speak to us, could help us make sense of our struggles with words. As I worked on Wolfstongue for several years, I watched its themes unfold in my family. For us these were the first years of school, and the years in which we understood that we are a neurodiverse household. We taught one another a lot, and realised how very much more we still had to learn.

At the start of Wolfstongue, Silas is being bullied at school because he has speech difficulties. Some boys call him 'Silence', ask him if he's as stupid as he looks and wonder aloud if he can say his own name. When he enters the world of speaking animals —a magic space called the Forest — Silas learns that the wolves are being persecuted by the foxes: the silver-tongued fox leader controls everything with his clever talk, and the wolves, who do not know how to speak for themselves, have become slaves in his underground city. Silas's sympathy is with the wolves, but if he is going to help them he will need to find words.

When words won't come

I found that with Wolfstongue, I was writing for myself as a child. Like Silas, I was quiet at school. My head was full of words but I could not speak them aloud when I needed to, and my sharpest memories of school days involve being shamed for not speaking up. It can seem impossible for all sorts of reasons to express ourselves to the world around us or to explain ourselves in a way that feels true - and if this is the case, we may feel that we barely exist, that we are barely human at all.

When he is with the wolves in the Forest, Silas finds he can begin to speak in the way that seems impossible in the human world. Gradually he realises that, for him, speech difficulty comes from the anxiety that overwhelms him when he is expected to speak; he is caught in the complicated force-field of other human beings, and all words fail. With the wolves it's different because they themselves are silent creatures at heart. In the silence of the Forest, Silas can find the inner stillness he needs — he can take the time to breathe deeply, to speak slowly and pause as often as he likes. Above all, he can learn that he does not have to speak just because others expect him to. The words come when he speaks for himself.

Words create the world

Take the word neurodiverse. I find it useful because it unites rather than divides. It does not sort us into categories, like 'normal' and 'abnormal' or 'healthy' and 'sick', but simply tells us that we share a neurologically diverse world, a world to which each person brings a unique neurocognitive profile. If we lack words like 'neurodiverse' we will be prone to think of a neurologically atypical person as having something wrong with them, or as doing something wrong. We will be liable to pity and to punish.

With a word like 'neurodiverse' in our vocabulary we can begin to think about how each of us responds differently to our sensory, social and emotional experiences. We can begin to make sense of the challenges and gifts of our neurodiversity, and to understand one another better.

Words have this power to help and to hurt us in our most private selves, but the same is true on the largest scale, in the way the human species makes its mark on the planet. Humans have imposed our language—our names, our stories—not only on one another but on the inhabitants of the non-human world. By telling stories of the sly fox and the big bad wolf we turn other living beings into symbols for aspects of ourselves. We could not have become the most destructive, most transformative species in the history of Earth if we were not so good at believing our own narratives. We have convinced one another that the wolf is a wicked, murderous beast, the embodiment of our nightmares, the better to drive it to the edge of extinction.

We have told a story in which human beings are fundamentally separate from the 'natural' world — in which the division that really matters is the one between human and non-human. It's a story that has carried us a long way over the past seventy thousand years, since we first began to tell stories at all.

How words can harm and heal

Every story has to end, though. When that happens the question is whether we can find the words for a new one. Our language creates the world we live in, but there is also a silent world, beyond human language, where the non-human beings live. We are going to need the words that unite rather than divide; the words through which we can understand that we are part of the silent world, too, and that neurocognitive diversity does not end at the limits of the human.

I hope Wolfstongue offers courage to anyone who struggles with words, with making themselves heard or communicating the truth of themselves. It's through that struggle that we come to understand how much harm words can do, and how much good. It's comforting to remember that there is a world beyond language, and to imagine how we could inhabit that magic space in the company of wolves. To get there we will need the words that do not break the silence.

Wolfstongue is our Bookmark Book of the Month for August. Read the review here.