"Children need to know that things can get better": Michael Rosen and Michael Foreman on writing about war for children

Published on: 22 Mai 2022

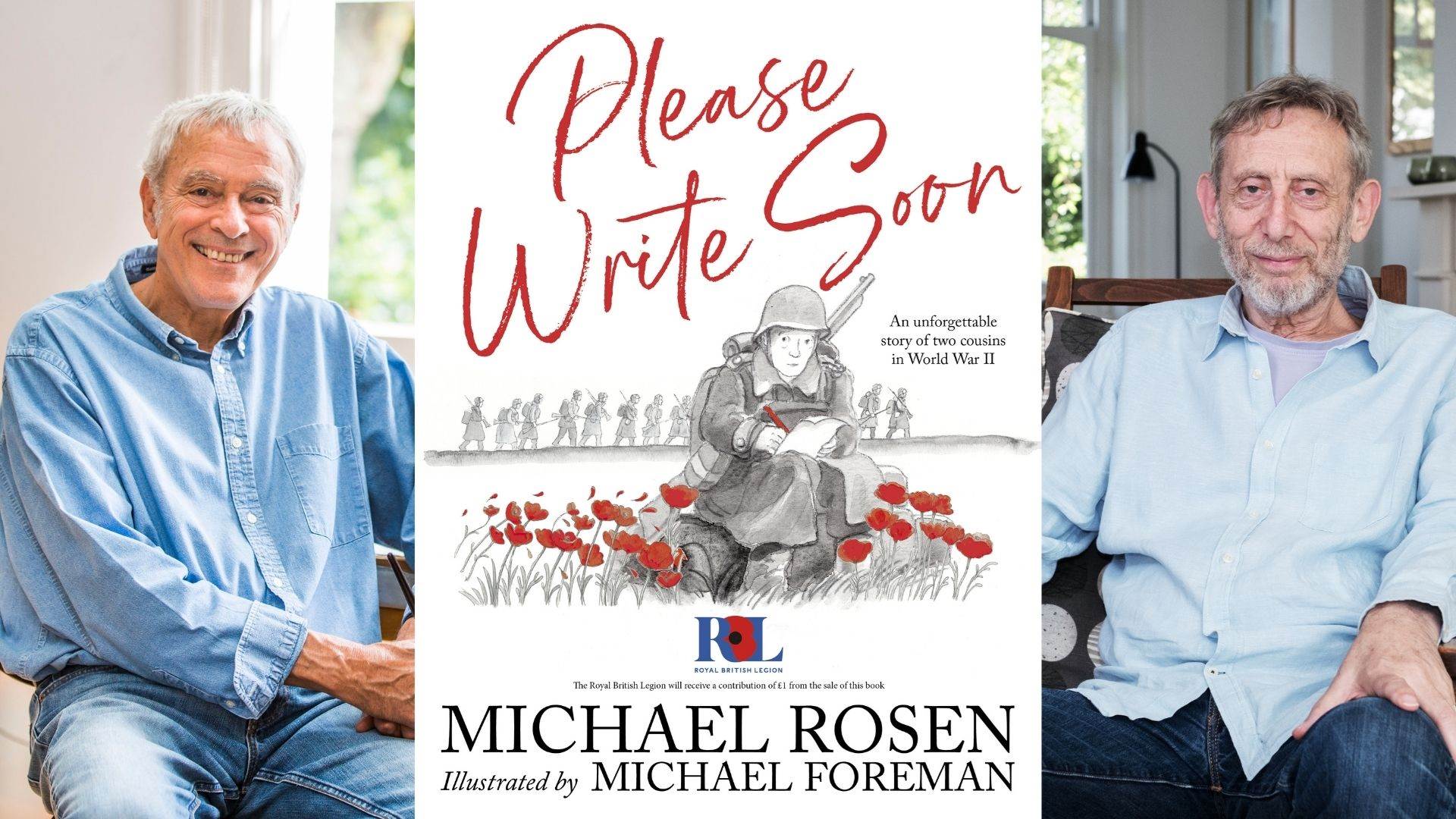

In their new book together, Please Write Soon, BookTrust Writer in Residence Michael Rosen and illustrator Michael Foreman draw on their shared memories of growing up in the wake of the Second World War; and today, with war, devastation, and displacement at the forefront of the news, discuss how we can talk to children about these issues.

Michael Rosen

Can you tell us a bit about your father’s cousin Michael, whose story inspired Please Write Soon?

Michael was born in 1923, and in 1939, his parents put him on a train to go to what is now Lviv in Ukraine – at the time it was called Lvov. He would only have been sixteen at the time. Michael’s family lived in Western Poland, but his family could see that things were going to get bad for them because the invasion of Poland had started – from Germany in the west and Russia in the east. One version of the story says that his mother went with him, but another version says that she didn’t because she was ill, but basically they got separated.

When Michael was in Lvov, his parents started writing to him. At the time, it seems that Russia was rounding up young men to go and work in the labour camos. Poland was divided: West Poland was invaded by the Nazis and East Poland was invaded by the Soviets. Because Lvov was in what at that time was Eastern Poland, now Ukraine, the Russians came in and Michael was picked up and taken to a labour camp.

At that point, the letters between Michael and his parents stopped, and as far as I can tell, very unfortunately they ended their lives in a concentration camp. But Michael didn’t know that then.

When the Germans invaded Russia, the Polish set up the Polish Free Army, which is sometimes known as the Anders Army. Michael enlisted in the Anders Army in either 1940 or 1941. So now, Michael, along with tens of thousands of other soldiers and Polish refugees walked from Russia, to Iran, down through Palestine and then on boats to Italy where they joined the eighth army, where they joined the Battle of Monte Cassino.

After that, the army was disbanded, and Churchill didn’t quite know what to do with them. So they stayed in Italy until the end of the war when they were shipped to Britain and put in what were called Polish resettlement camps. Some people stayed there until 1950 or 1951. In Michael’s case, he got out in 1948.

He lived until last year. Michael had two sons, Grant and Barry, and they had never translated the letters from Michael to his parents, so I got them translated earlier this year, and they inspired the book.

Do you think children today can feel a connection to World War Two – they study it in school but do you think they can really understand what it was like?

Probably not, no. I gave a talk about it in my old school the other day and I tried to make it immediate for them by saying “Look at me: the war ended just before I was born. So you’re looking at someone who wasn’t in the war, but the whole of the time I was growing up, people talked about it,” But in terms of it being a real lived experience for the children and the relatives they know, then no. The very last veterans are leaving us now. Someone born in 1935 will have a pretty good memory of the war, but we’ve got to remember that they would be 85 now. So children might know someone that age and talk to them.

There are movies, of course, and if anything, technology and the internet has enabled us to have information and video about World War Two at our fingertips whenever we want it. When I was a kid and people talked about World War One, there was hardly any pictures of what London was like, even though London was bombed quite badly in the first world war. It had a kind of mythic feel about it because there wasn’t much to really see. Nowadays, parents and teachers can make it much more real for kids.

What would you say to the children who are worried about the wars taking place in the world today?

Wars are terrible and awful, and really I can’t offer much comfort or consolation, I’m afraid. I’m very anti-war myself. I’ve never seen any glory in war, and all wars end in people sitting down and coming up with an agreement: in an ideal world, we’d come up with the agreement before the war.

I say to young people, wouldn’t it be great if we could study peace as much as we study war? And though some people say war provides a solution, it’s peace that actually provides a solution.

The other thing I would say is that, in war, it’s ordinary people, not in uniform and without guns, who always end up losing, no matter what side they’re on. German people lost World War Two, but so did we because we got bombed. Our relatives and friends died. So although we were on the winning side, the people always lose in war.

We have Armistice Day and we have the Cenotaph to remember the men and women in the armed forces that died in wars, but we don’t have a day to commemorate all the civilians who died in war.

I’m very pleased that there is soon to be a Holocaust memorial in London, but I think it’s strange that we don’t have a place to go to think about the non-military people in Britain, mostly in the major cities, that died. Somewhere we can go and think, isn’t this sad and awful. So I would say to young people: maybe one day you could help to make a place like that.

Did you draw a lot on your dad’s life in creating the character of Solly, writing to his cousin Bernie – the character of Bernie being his real-life cousin Michael whose story you’ve told us?

Yes, to some extent. Like Solly, he was brought up just by his mum. And he was also evacuated as a young adult, so that part of Solly’s story was based on my dad too. In fact, Solly’s rather severe teacher in the book, Miss Drury, actually existed, but she was one of my teachers! She had a sort of soft spot for me. She was very severe and strict, but she would always look at me with a bit of a twinkle in her eye, and what she says to Solly in the book is what she used to say to me: that I’d either end up being a master criminal or do something brilliant.

BookTrust Writer in Residence Michael Rosen

BookTrust Writer in Residence Michael Rosen

Michael Foreman

Hello, Michael. Congratulations on Please Write Soon! It’s such a poignant, brilliant book.

Thank you! When I first read Michael’s story, it reminded me instantly of my own childhood growing up in World War Two. It was so moving and heartfelt. I knew immediately it was a book I wanted to illustrate.

I drew upon my childhood memories of air raids and bomb sites, and hiding under the kitchen table with my mum, just like in the book. But when I received copies of the book, I was shocked at how current and relevant all of it was to what was happening now in Ukraine. When I was doing the drawings of the bomb sites and the families pushing prams, with their suitcases – trying to salvage the basics from their lives and not knowing where they’re going - you can just turn on the TV and see all of that now. People being forced out of their homes and being bombed.

Kids don’t have to delve into history to know what it was like in World War Two. Children know so much about the world now through the TV, and there are so many terrible things happening, so it puts rather a responsibility on people making books for them.

But books are a great tool for parents and teachers to use to help children understand things like war, aren’t they – especially when it’s as sensitively and thoughtfully presented as Please Write Soon.

Yes. It’s so important that a book like this is shared at school or at home with adults who know the individual child and can anticipate how these topics will affect them. Far be it from me as someone who makes those books to pretend I’m some kind of great psychologist or something, but each child is different and the input from the adults around them is really important.

This isn’t the first book about war you’ve made, of course.

That’s right – the first book I ever did, The General, was a pacifist book. The Americans called it “A Communist tract for the nursery”! Then I did War and Peas, which is about war but also about poverty in developing nations. Lots of others too, of course – Two Giants, War Boy, War Game, Stubby, Poppy Field with Michael Morpurgo. It really has coloured the direction that my career has taken, and I think that’s because what happens in your childhood affects your life so much.

Were there parts of the illustration in the book that you had to research, or were you solely drawing from memory?

I had to do a bit of research on Wembley Stadium! Also, as the book is in two colours, it follows on from Poppy Field https://www.booktrust.org.uk/book/p/poppy-field/ with Michael Morpurgo which had the same style, red ink and pencil. And as well as the red for poppies and remembrance, we stuck with red because of Michael’s love for Arsenal Football club! To be fair, it wouldn’t have worked as well if we had used blue for my team, Chelsea.

The letter format of the book is really lovely – do you have any family letters still from World War Two like Michael’s, which inspired this book?

No, because there were no members of my immediate family away during the war – my dad had died just before the war started. However, my mum ran the village shop where we lived in a little village outside Lowestoft on the East coast. All the soldiers that were billeted in the area would come in for a cup of tea and cigarettes and so forth, and on a Sunday afternoon they’d come around and play cards. The soldiers were there because they were doing training on the beaches before going overseas. There were American air bases behind our village, and Lowestoft was a naval port too so there were always lots of sailors around. But all that meant that we were a big target for German air raids.

Also, there were German prisoners of war working on the farms around the village, a bit like in Please Write Soon where Michael is working in the work camp in the forest, wearing a red armband. The German prisoners of war had white circles on the backs of their jackets. Anyway, we used to play football with them in the fields, and some of them became friends and they’d also come and join in the card games on a Sunday afternoon. So, on Sundays, there would be British soldiers and German prisoners of war playing cards in our front room. In fact, my cousin Pam married one of the German prisoners of war.

I say goodnight to my mum every night even now, because she was such a tour de force. She was a mum to all these soldiers and prisoners of war who were far away from home. And after the war, my mum used to get letters from them still. One of them, a Scottish soldier, visited my family just ten years ago. So many of those young men wrote to my mum: they never forgot how she helped them.

What would you say to children now who might be worried about wars going on the world?

The subject shouldn’t be avoided: it needs to be discussed, but the important thing I think is that at the end of the conversation or story, children are left with a feeling of hope.

Children need to know that things can get better; that they themselves can make things better. Together, we can still make this world a better place.

In making a book about war, I think it should also always be clear that peace is the aim, and the book should address the stupidity and futility of war. At the same time, how important family and friendship is. Family, schoolfriends – children all the world being friends together.

Illustrator Michael Foreman

Illustrator Michael Foreman

Topics: Historical, Writer in Residence, War, Family, Refugees/asylum, Features, Michael Rosen