How the safe space of books can help children understand big world issues

Published on: 5 Mai 2021 Author: Ele Fountain

Author Ele Fountain explains why she writes about hard-hitting subjects, from refugees to climate change, to empower young readers – and why it's important to give hope and adventure, too.

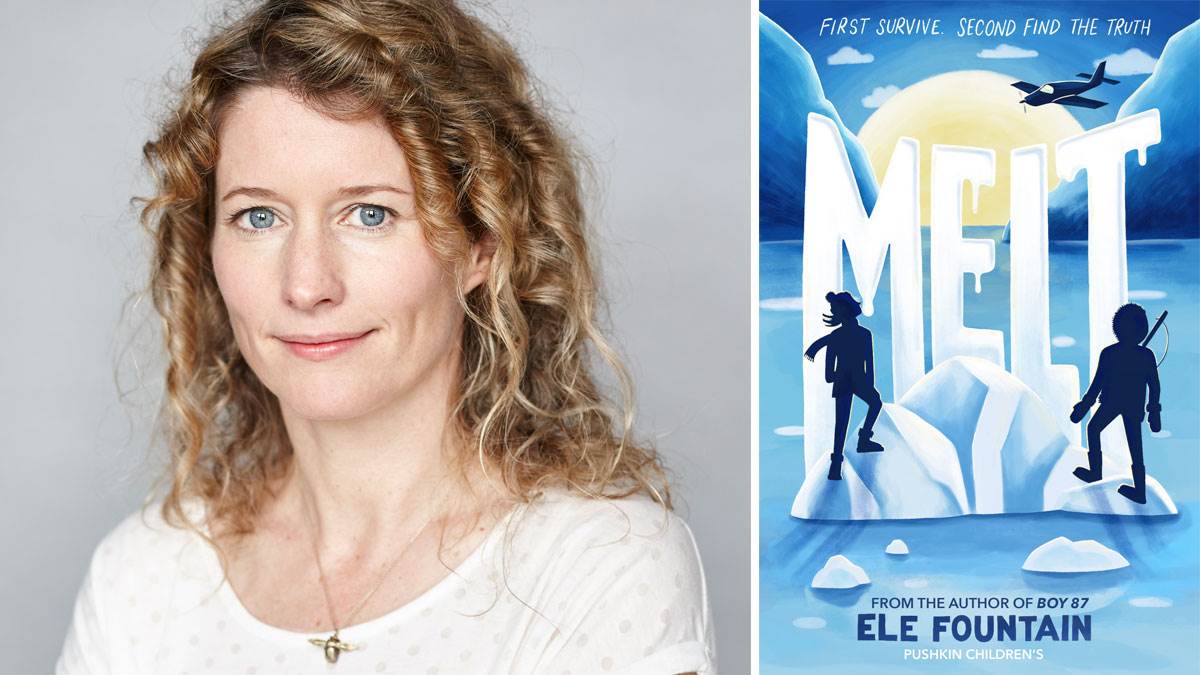

Photograph of Ele Fountain (credit: Debra Hurford-Brown), author of Melt

Photograph of Ele Fountain (credit: Debra Hurford-Brown), author of Melt

My daughter (aged 6) asked me: ‘Mummy, why is that man lying in the doorway?’. We started talking about homelessness. It’s a complex issue. I knew what I wanted to say: to give reasons, to be honest, to be reassuring, too. By the time I had this all straightened out, the moment has passed. But the subject lingered in her mind, and we talked about it later.

Children notice everything. They know far more about the world than adults tend to believe – or want to believe. It’s not just what friends mention at school – it’s images on the news, snippets of conversations. Not being able to join up the dots, to make sense of big issues, can make them feel anxious. Disempowered. Kids want to be able to control the world around them just as much as adults do but have fewer tools. The best tool is understanding what you want to change.

Touching stories all around us

I write about things that have really touched me. Things I want to change. My first novel, Boy 87, came from living in Ethiopia. It hosts the most refugees in Africa but thousands of people flow across the border in the opposite direction too, trying to escape persecution within Ethiopia. Refugees end up caught in a no-mans-land of camps and border crossings, making desperately dangerous journeys as they seek safety. In Boy 87, I wanted to write about these journeys, the ones made before refugees even reach the coast. Journeys which may take years, and their life savings.

Around the same time, while living in Addis Ababa, a more specific event affected me. I saw street kids most days, but on one occasion, I drove past a girl begging at the side of the road, alone. When I was able to return, later in the day, she’d gone. I discovered the girl was trying to get money to take her mother to hospital. Her mother had been lying in the adjacent street. The girl was about 4, my eldest daughter’s age at the time.

When that very same daughter asked me about the homeless man, I thought back to the girl, to the street kids who lived with no safety net of any kind, no one to kiss them goodnight. It’s a tough subject. But kids already know about it. Or they will have heard something. Seen something. From this came my novel, Lost. A story of street kids.

These subjects infuse our daily life. They are all around us.

But why use a book to talk about them?

Magic doorways into other worlds

Stephen King describes books as ‘a kind of portable magic’. Part of this magic is to show us other people’s worlds, to step into other people’s shoes and experience what they might be experiencing. A book is just words, the reader and their imagination, a simplicity which makes it easier to see things through a character’s eyes and helps us to empathise with them.

When we watch TV, we mostly see things happening to other people. When we read a book, it’s someone else’s words, but your own imagination which brings it to life. It’s an intimate, unique kind of experience.

Through this power, books can let us ‘try out’ the world before we might experience things for real. They can provide a framework to explore big subjects and guide readers through possible outcomes in a safe space. Subjects like divorce, bereavement, homelessness, the refugee crisis. Books don’t tell you how to feel but can help you understand the feelings you have. It’s possible to go back and re-read bits which need more thought, or show them to other people, talk about them.

It’s not surprising, then, that studies show reading for pleasure increases children’s resilience and feelings of wellbeing.

‘Pleasure’ is the key word. There’s no point writing about big subjects without making the reader want to keep turning the pages.

Reading for pleasure can be a case of letting kids read what they want, rather than what adults want them to read, and kids are truly the most discerning critics.

This is where stepping into the characters shoes becomes helpful for the writing part, too. Whatever white-knuckle ride your character is experiencing, the reader will experience. That’s partly why I love writing in the first person.

Climate change as a main character

Big subjects can be my motivation to write, but the story itself must always come first. Often my characters arrive unannounced. Then I think about how the characters will respond to the themes I’m writing about. What kind of journey will they go on?

When I began researching my new book, Melt, I realised there was a third main character. A powerful character with moods to match. A character which could be calm and serene or angry, even violent – rarely anything in-between. I knew that this character held the key to an exciting story, a page-turning adventure. It just so happened that this character was also my motivation for writing the story: the weather.

The weather was my third and most imposing character, making its presence felt throughout the story. Climate change is a phrase on everyone’s lips. It’s everywhere in the news. I wanted to write a story which would show how our lives are tangled up in the causes of climate change. In the process, I learnt about communities that have lived for centuries in harmony with some of the harshest weather on the planet.

These communities cannot keep up with the pace of change. Sometimes, the future looks bleak. But I also Iearnt about how human beings can adapt. About the incredible things which happen when we do. This provided me with the other ingredient which is, for me, at the heart of these kinds of adventure stories – hope.

The best stories, whatever themes lie at their heart, must give us hope for the future.