'The shock is hard to get over!' Elmer creator David McKee on winning BookTrust's Lifetime Achievement Award and his incredible career

Published on: 23 Medi 2020 Author: Emily Drabble

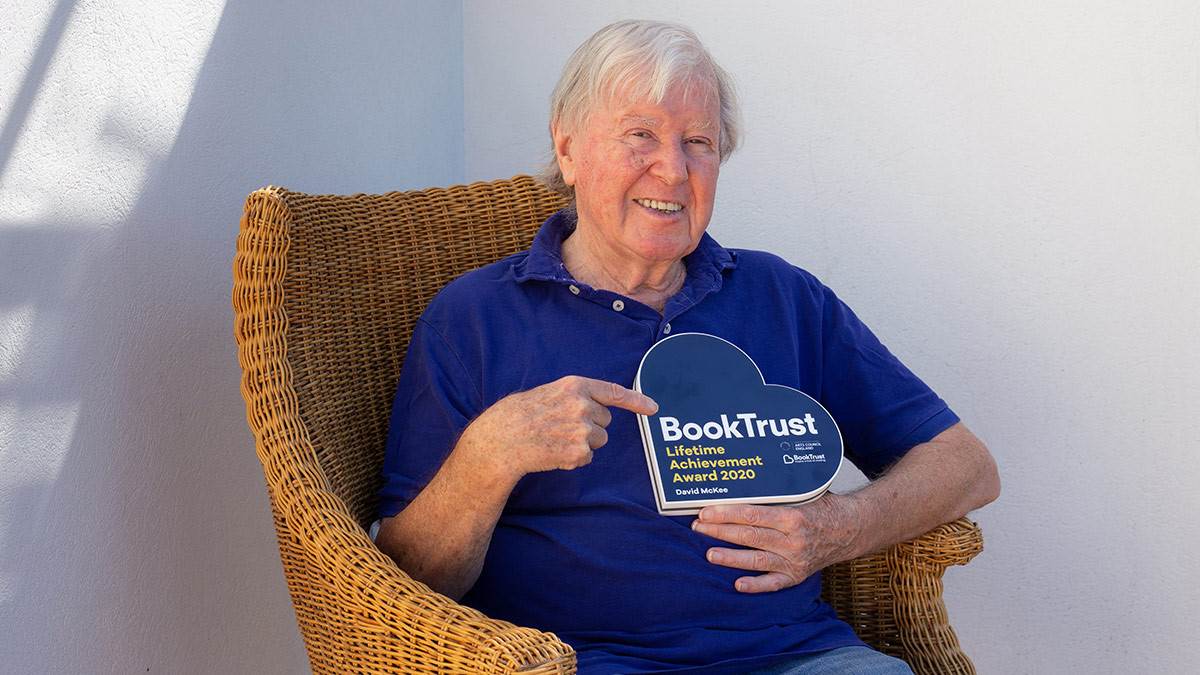

David McKee has won BookTrust's Lifetime Achievement Award!

Here, he tells Emily Drabble how he created his classic books - from Elmer to Not Now, Bernard and Mr Benn - and explores the roots and inspirations of an incredible career spanning over 60 years.

Did you want to be an illustrator when you were growing up?

I was born in 1935 in Devon, and honestly didn't even know jobs like being an illustrator existed! I mean, I drew a lot, and I was encouraged to draw - I think probably to keep me quiet. My mother would give me paper and that was probably to stop me drawing on the walls! I was usually top in art at school, but that was not what one did. It wasn't a proper job. I think I was expected to go and work with my father. After the war, he repaired farm machines and later he started selling them.

So tell us about your road to becoming the illustrator we know and love?

One day at grammar school, one of my masters asked us all what we'd do the following year. I said I was going to work with my father. And it was at that point that I thought about it for the first time - I'd just accepted it before. I realised my father had two weeks of holiday a year and he was working 48-hour weeks. And I realised the only thing I liked about school was the holidays and that I was on three months of holiday a year!

The only way I could keep that three months, I thought, was to stay at school, and the only way to stay at school was to be a teacher, and the only thing I could possibly think of teaching was art, because I was alright at that. And luckily the teacher advised me to go to art college first, not straight to teacher training college. So I went to Plymouth College of Art. Then I thought, 'What's all this business of three months off? I want the whole year for me, thank you very much!'

I did go to an arts specialist teacher training college after my degree in London, but I realised I didn't want to teach. However, a teacher sounded quite respectable for my mother to say I was going to be. She died at 95, and I think she was still waiting for me to get a proper job! In England, I think if you said you were going to be an artist, that wasn't acceptable to most families - and that's probably still the case now.

What were your favourite books as a boy?

Winnie the Pooh and Treasure Island; these were books that were read to me, and lots of people told us stories.

How did you actually get your first book published?

I realised while I was at college that to sell paintings and earn a living - enough to eat - was going to be difficult. I was going to have to find things to bring in money. There was a student ahead of me at Plymouth Art College called Roland Fiddy and I'd admired his ordinary drawings at college and later I noticed he was doing cartoons. I thought maybe I could do that too.

So I set about drawing what I thought were humorous drawings. I'd draw ten cartoons and send them with a stamped addressed envelope. Usually they'd send them all back in the other envelope but sometimes they would keep one, and later you'd get a cheque - they paid in guineas, it was a professional kind of fee. This would be in the 1950s when I was still at college and by the time I left college I could just about keep myself by drawing cartoons.

I became interested in certain cartoonists who were more than 'joke men' but artists. There were two in particular: one was Saul Steinberg in America and the other was André François in France. Interestingly, they were both Romanian by backgound. And they affected all my generation - the influence was very strong. I discovered a book by André François called Crocodile Tears - it was in French and English and a very good book. I used to tell stories to friends at college and I thought, 'I can do this'.

So I made my first book Two Can Toucan in exactly the same way as I would do with the cartoons. I drew it up and sent it off. When the book came back from publishers it might have a comment saying something like, 'All that colour is too expensive', so I'd do it in a different way. The first books were redrawn several times and sent off several times - I did it all by post. Then I had Two Can Toucan accepted by Abelard-Schuman - this was a branch of an American publishing company that Klaus Flugge headed up in London.

The first version of the book, because there are now two, was with hand-separated colours, so that meant making multiple drawings painted in black with a brush, a separate drawing for each colour. But that's the basis of lithography, and was fine, I'd learnt that at college. I had an offer of either a flat fee or a royalty, and because I believed the book was going to be there more permanently than a newspaper I decided on the royalty and that I would make money in the end. So it was a £75 fee with royalties or an outright sell for £150. I made the right choice, I think! After Two Can Toucan, I was off!

What happened next?

While I was working on that first book Two Can Toucan, I also made one called Bronto's Wings, so that was my second book. All through the 60s I wrote a lot of children's books, but did a lot of humorous illustrations too. I drew for the TES every week and regularly for Punch and all that was quite important to me.

Once the books had started, I continued with them. I liked that they had a kind of permanence - one of Klaus Flugge's big things is keeping certain titles in print, and that has been fantastic. A lot of publishers don't do that because it's quite expensive. But I think when teachers are using your books, the books need to be kept in print for them.The world would be a much poorer place without Klaus Flugge, that's for sure.

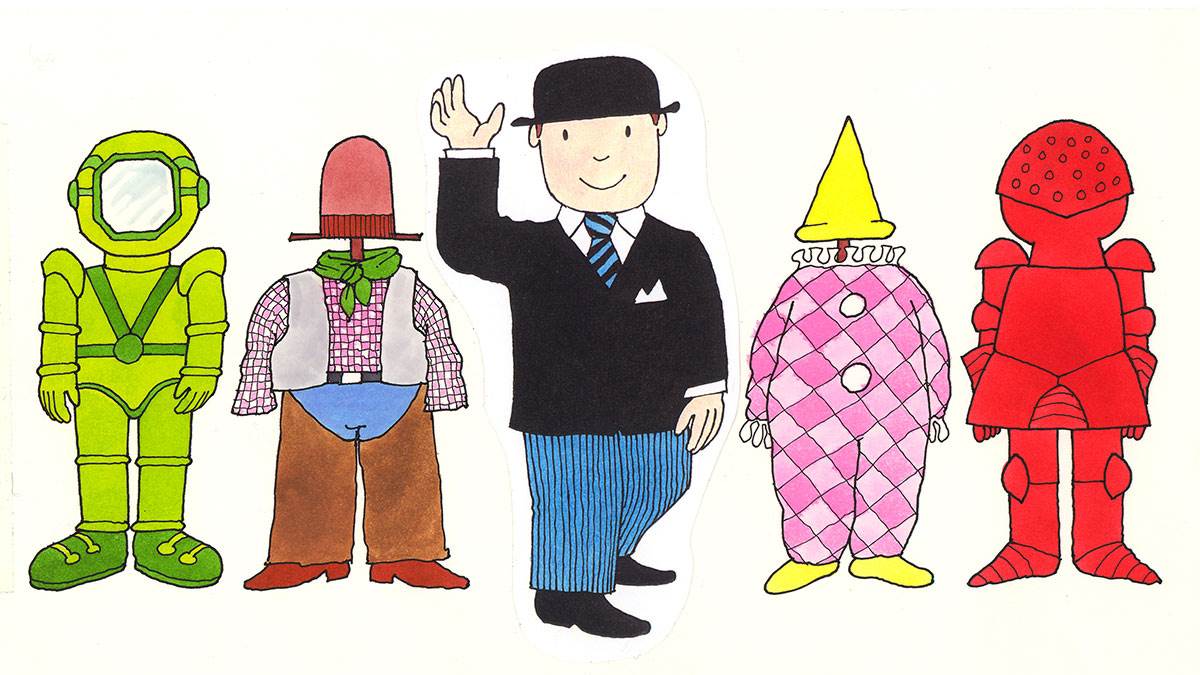

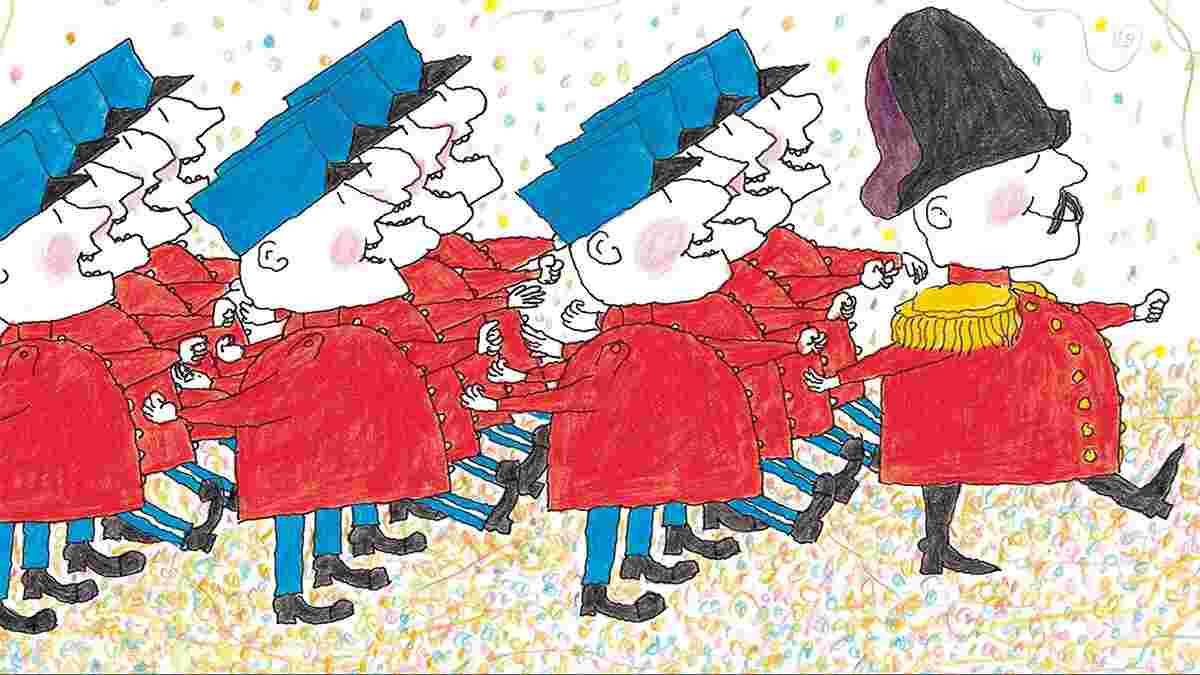

Then in 1969, the BBC asked if I would be interested in making a Watch With Mother series, and that's how I started to make Mr Benn, so then for a while films were the most important thing for me.

Licensed by Factory Rights Limited

What was it like to make children's books at that time in the 1960s?

There were quite a few small publishers and one of the things which was important was they all loved books. I was asked once in a conference in Mexico what I demanded of my publisher. The thing that I wanted is that he or she would love books. Of course, with Klaus Flugge as my publisher that was very much realised - not many people love books like he did and does. He's a great guy as well!

It was an exciting time to be making picture books. First of all, there was the sudden change in printing techniques - suddenly you could do full colour, it was separated and there were these really colourful books. I think I was lucky to be there at the time. I don't think I could make it now if I was starting out!

Parents hadn't seen the kind of books that were coming from John Burningham, Brian Wildsmith and Michael Foreman. Parents were buying children's books for themselves - because they hadn't seen picture books, they were open to them. It was that visual period with Biba and all the rest of it. Now the bookshelves are full - if you're doing something, it better merit its place on the bookshelf! Now parents have seen the books, are used to them and a bit blasé.

In the swinging sixties, I was a young parent and I had three young children so I wasn't out and about that much! But thinking about it afterwards, I suppose I was involved - I was doing lots of advertising and actually was contributing images which were part of the 60s, and the books of course.

Did you write your books for your own children?

No. It's always been for me really, I'm a very selfish chap! But they were involved, in that I would tell them the stories, and we always had lots of children's books in the house. And they influenced me probably by their drawings, and especially by their attitude to reading a book.

I'd have a book flat on the floor and I'd be reading it from the normal position and I'd have one child looking from one side, one from the other and the other one sitting in front of me reading it upside down. I realised they read images upside down perfectly well, and that was one of the influences for me. And there were many others - for example, Medieval war scenes which have inspired my perspective 'mistakes' (as people tell me).

How important are the adult readers of your books, who read the book to the child?

The picture book is the one book that is shared by an adult and a child, so you've got a double audience. Why not work for both audiences? I like it when a book works for an adult as well as for a child. Adults have to read them every night so you don't want them getting bored.

When I made the films for the BBC, the series was titled Watch With Mother. The title was later dropped as I suppose it was too sexist, but it was a nice title in a way because you were conscious of the 'with' - the double audience.

It was also nice because they repeated the series, and that repetition is what a child likes - there's the need to read the same book over and over. I think part of that is security, they know the story and can go through dangerous waters but they're going to get out the other end because they've heard the book before. Certainly I've always been very aware of my adult audience and the books are partly made for them.

Do the ideas come to you as the story or as the look and illustration?

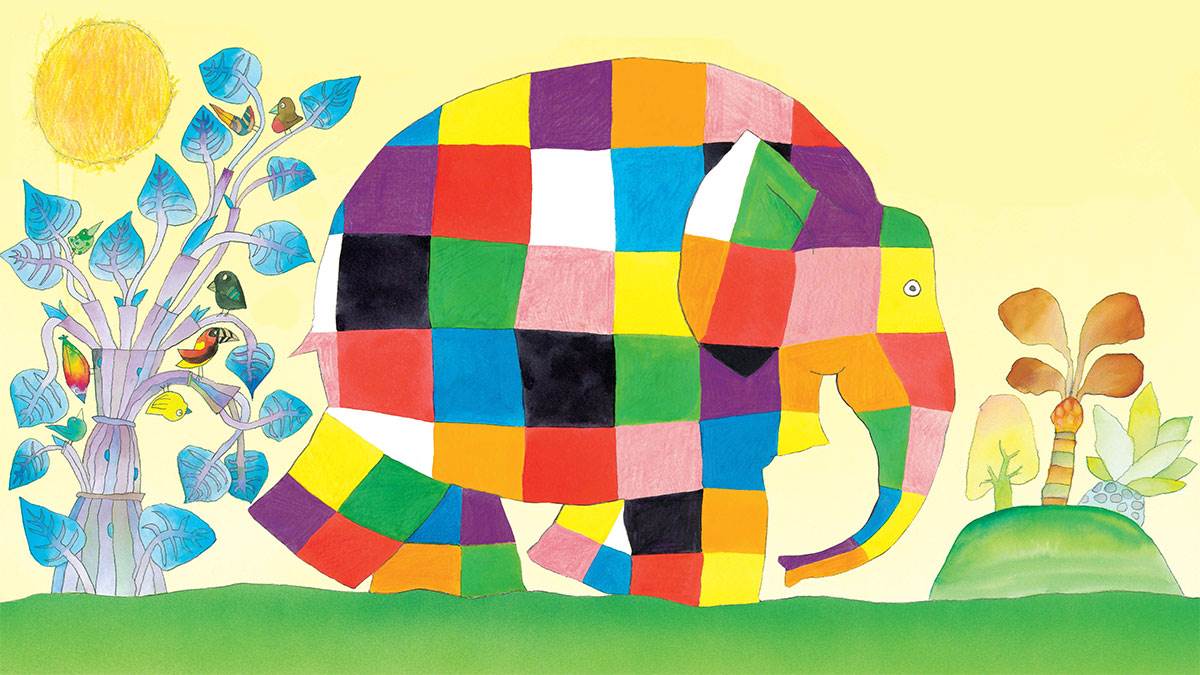

It's one or the other. With Elmer, it was the image of Elmer first, then the name, then the story. But other books, like Not Now, Bernard, come as the story and the image you work out later.

Tell us how you make your books!

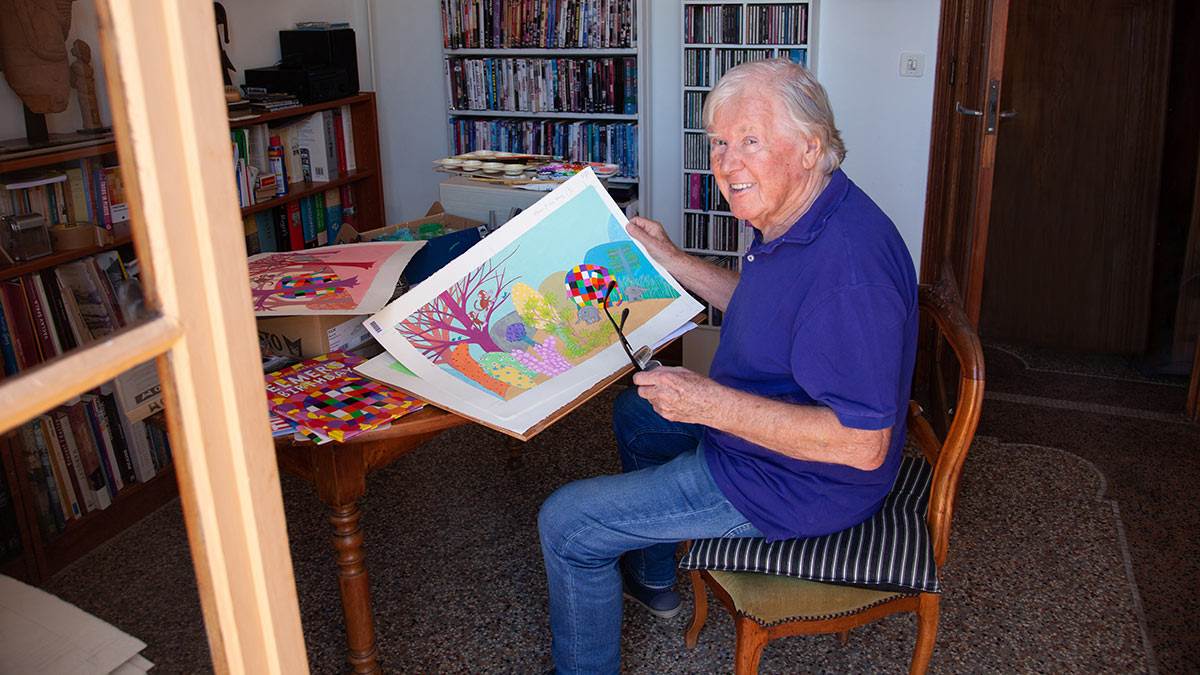

I may make a very vague storyboard, with small pictures to look at how it would work out. I'm working on an Elmer book now and I've drawn all the book and now I'm going through and painting it. I'll have to go through again to correct it, and there's always a chance at the end that I'll reject all of it and say no. That's happened to me - it's a living kind of thing. In that way, it's a bit like a painting - work a bit here and a bit there.

Where do you work?

Oh, anywhere. Absolutely anywhere. I have an area which is allocated at the moment where I am in France. It happens and you just work. If you're on a plane, that's where you work.

Do you keep a sketchbook or notebook where you jot down your ideas and do sketches?

No. I used to carry a sketchbook all the time but I don't do that so much now. Just lifestyle changes - and I'm not so selfish with what I'm doing.

Are there germs of books in your notebooks that you haven't created yet?

Yes! I've got written stories, good stories I think, that I'll never make into books. That used to worry me at one time, that I'd have a book that I'd be working on and I'd die before it could be finished. And then one day I suddenly realised that no matter what I did, as soon as a story was done, there was another one anyway so it didn't really matter.

Do your characters come alive to you? Do you talk to them? Does Elmer whisper in your ear at night and tell you to write more books about him?

He doesn't come at night, but yes! It is the case of knowing the characters and revisiting them and wondering what they're up to at the moment. I suppose I've never analysed the process really, and the nice thing about stories is that you've got that start and then you're carried with it. You want to know what happens.

At the beginning it's like singing blues. You start singing. You don't know where the end is, but at a certain point you know where it's all going. It's like jazz. And then you're fine - you can do what you like because you know where the end is.

What does is feel like to finish a book?

It feels like, 'Oh, thank God for that!' Usually there's another one waiting, or somebody saying, 'What's the next one?'

So you're 85 but you're still very much working on new books all the time?

That's what you do - you can't stop. Nowadays I work more slowly I suppose. If I get five hours of work done that's fantastic, but there are obligations to go for walks, or some bread, which you don't think about when you're younger. And also there are things like arthritis which we older illustrators seem to get that slow you down. I sleep more - older people are supposed to sleep less, but I sleep more. When I was doing the Mr Benn films - the books, the magazines, the cartoons - I was sleeping four hours a night! And all the rest was work. Now I quite like eight hours in bed. I'm happy to take a bit extra and a siesta, which I like!

You don't have the internet at home - is that a specific way of life?

I've stayed in the past, really, doing everything by post. I saw all the trouble that everybody else was getting with it and I thought, 'I don't really need this, I don't even wear a watch'.

Which of your characters do you think most resembles you?

Well, they all do. I think it's all self-portraiture in a way. When I look at things, and when I realise what names I use for certain images, I realise how much comes out of the past.

Who are your biggest inspirations?

Well, I think I've been influenced by everyone actually - mostly painters, or Steinberg and Francois, who I talked about earlier in the graphics side. From the painters just everybody, including Medieval war painting which affected the perspective in my books, and Prussian miniatures, where perspective works differently and I've used a bit in different illustrations.

I was very influenced by Paul Klee; the drawing as well, the fine line that bites, and influenced by his thinking a bit, his attitude to drawing: he said drawing is taking a line for a walk. Even the art teacher at my primary school who taught us how to lay a wash, and to paint the big areas first because they are the most boring! I think they all influenced me. Other students influenced me, and it's probably pretty visible the people who influenced me. I admire the work of other illustrators that I know so much.

Your books have been used to deliver philosophical concepts to children and to help teach them about inclusion, prejudice and violence and peace - especially Tusk Tusk and Elmer. Is this your intention when writing them?

It's a mix. For the obvious one Tusk Tusk - that's what it's about. The world is full of differences and we have to accept all differences. How boring it would be if we were all the same!

My book The Conquerors came about because of the Iraq war, but it was a story I wrote when I was in college in the 1950s! When people ask, 'How long does a book take?' I think of that one. It took over 50 years! When I was in college it was not long after the Second World War, so the older students and the younger members of staff had been released recently from the forces. And one of them, a young assistant at the college, had gone through Italy with the army - I suppose you could say they were releasing Italy. All he could think about was getting back to Italy, and how much he loved it. That was the basis of The Conquerors, because it's the culture that in the end wins. And so there have to be other ways to deal with things than war.

Some people might say you should keep deep themes and dark subtexts such as the pointlessness of war out of children's books. How do you answer?

Well, there's plenty of space for both, I should have thought. It's up to parents to select the books for their child.

How important are children's books to guide the world to be a better place?

I don't think there's much chance of that! Books can change people's attitudes, but you can see what's going on at the moment - it feels like the end of mankind!

I do think children's books can contribute and are very important. It's the children's books which create the fans for adults' books. Without the children's books, the adults' books wouldn't have any public. Also, children's books are a way to access the art world, and in some of my books the illustrations are more important than the story.

How does it feel when people tell you they have been inspired in their career choices by your work?

Well, that's the bit that's quite frightening because you are influencing them! Some young guy was telling me how much the Mr Benn films influenced him one time, and I thought to myself, 'How can people possibly say the films with excess violence and sex don't influence children if an innocent film like Mr Benn can!' You do have to be wary about what you're giving children.

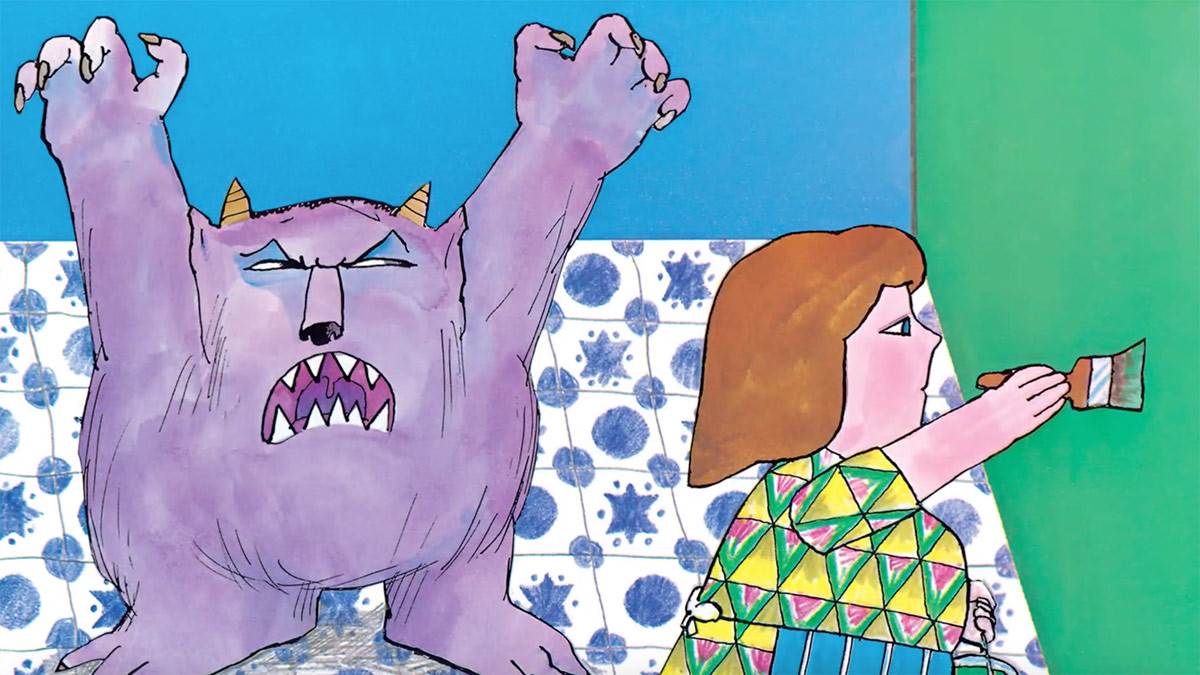

Not Now, Bernard is iconic - but is the monster Bernard, or did the monster eat Bernard? More people think the former, but what do you say?

I don't definitely say either way. Lots of children have written to me to say, 'The monster is Bernard, isn't he?' They understand that we all have a monster inside us that can eat us up. You see it with road rage when quite normal people shout, hit the horn and so on - the monster is eating them. And that has to have a control!

If you just ignore your children the risk is that the monster will eat them up. Now it's the opposite with computers and video games, of course - you might see a parent saying, 'Come and have dinner, it's time for bed', and the child might easily say, 'Not now, Mother!'

We can't imagine a world without Elmer. Why do you think he is so beloved, and has his success surprised you?

I suppose it's not something I consider. I'm very grateful that he is such a success and I hope it continues. I suppose I find myself interested to know if in 50 years time, people will still look at the book. It would be nice to think they would. That would be a kind of permanence - sometimes we shout acclaim too soon!

But Elmer first started in 1968, so I would have been working on him in 1966. He's been with me quite a long time. Last year I said, 'Perhaps I won't make another Elmer book'. But then I stopped being tired and said, 'Now, what was that story you told me? Hmm... I'll do it'.

Do you have Elmer toys around your house?

Quite a few bits and pieces - there's some Elmer pottery we use every day. There's a big Elmer on the settee and other bits around - a lucky Elmer keyring. I'm not sure visiting my house would feel like being in an Elmer book as we have mainly wooden furniture but the paintings (as I still paint) are fairly colourful!

How does it feel to win the BookTrust Lifetime Achievement Award?

Well, in a way I suppose I don't really believe it. It just doesn't seem possible. I've never been really one to get awards like that. I can't help wondering if somebody has mistaken me for someone else! It's obviously fantastic that it's happened, but it is a total surprise - the shock is hard to get over. Well... I suppose I see myself differently.

Desert island books question: if all your books had to be destroyed, which one would you keep on your desert island?

I'd probably prefer a blank one.

Do you have any tips for new illustrators out there?

Yes, get some other kind of job... I'm joking! The only thing I would say is don't expect to get rich or famous. Just enjoy it. If you're not enjoying it you're in the wrong game. If you are enjoying it, if you make it, that's fantastic. But if you don't, you've still enjoyed it!

Topics: Picture book, Classics, Lifetime Achievement, Interview, Features

David McKee booklist

Check out our list of some of our favourite David McKee books, from Elmer to Mr Benn and Not Now, Bernard.

Why David McKee is so special

Authors and illustrators celebrate the news that David McKee has won the Lifetime Achievement Award, by explaining what he means to them.

Add a comment