'Like adding an extra shot of espresso': The powerful impact of reading to babies (and the science behind it)

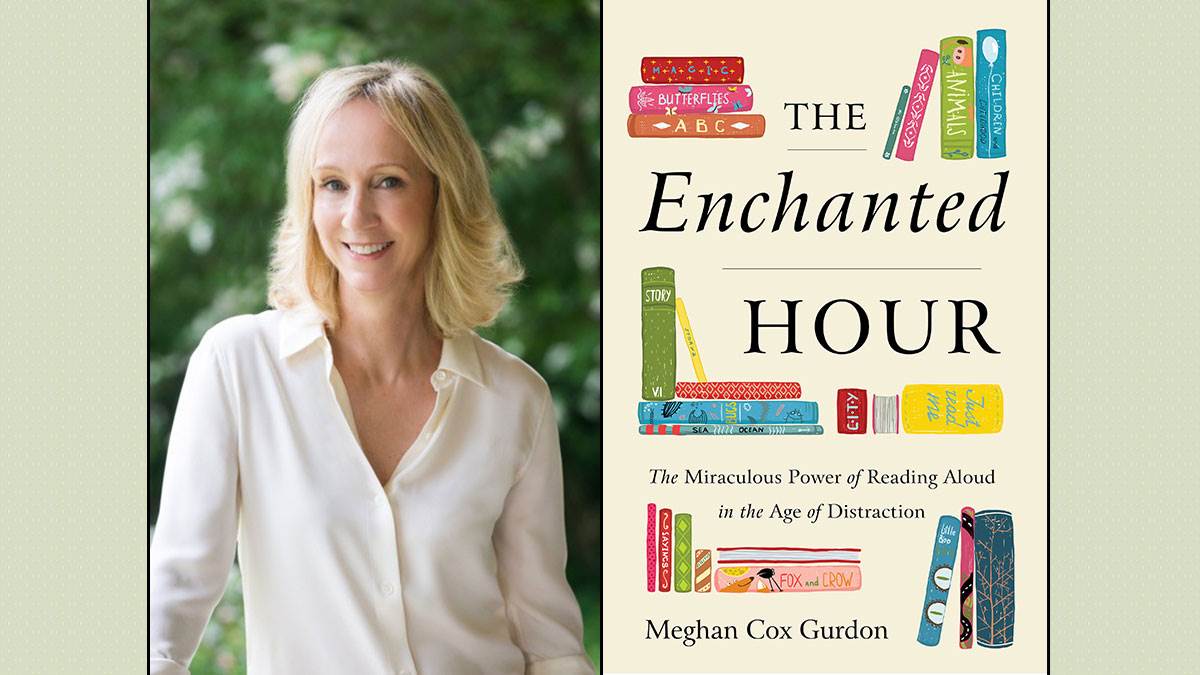

Published on: 7 Chwefror 2019 Author: Meghan Cox Gurdon

Meghan Cox Gurdon has written a new book all about the incredible power of reading aloud - and in this extract from The Enchanted Hour, she shares why it's just so important for babies.

Reading aloud is good for people of every age, but its effects are perhaps nowhere more keenly felt than in infancy and early childhood.

There are good reasons for this, not least the galloping pace of brain growth in a child's first three years of life. Reading to children during this period gives them more of exactly what they need: more loving adult attention, more language, more opportunities to experience mutual engagement and empathy.

Picture books enhance the time parents and children spend together. It's like adding an extra shot of espresso to a café latte: one cup, extra zing.

And then there is the role that stories play in what the novelist Shirley Jackson called 'the nightly miracle'. Bedtime is manifestly sweeter, happier, and nicer when the electronic devices are put away, the books come out, and everyone settles down. A busy day of transactions - spooning cereal (and eating it), washing faces (and being washed), changing nappies (and being changed) - yields to a quiet time of mutual encounter.

How babies soak up the world around them

Illustration: Kate Alizadeh

An infant won't know much about any of it, of course. He won't remember hearing about Pat the Bunny or a Very Hungry Caterpillar. He won't have any trace of a wisp of a recollection of sitting on anyone's lap and reading Peepo! or any other book.

Yet long before a baby is old enough to interact, before the first reciprocated smile, before he can control his head, or sit up, or muster the motor skills to 'find the mouse' in an illustration, he is drinking in sounds, responding to affection, and, through his brand new eyes, learning to distinguish one object from another and to see patterns in the world.

Hogwarts and the Hundred-Acre Wood are destinations years in the future. But almost from the moment a baby arrives, he's paying attention. And why not? He has everything to learn.

In the beginning, there's the muffled cacophony of the outside world, a mother's heartbeat and her reverberating voice. (At least, that is the assumption, as Dr. Abubakar said.) What follows is an extraordinary, seamless process as the amorphous surrounding sounds of a native language separate into syllables, which at some point in the future become discrete words.

Illustration: Erika Meza

'Language comes at us at an incredibly fast pace, and we need to be able to group things together very quickly, otherwise it's just impossible to understand,' said Morten Christiansen, who runs the Cognitive Neuroscience Lab at Cornell University. Learning a first language is a complicated developmental exercise that involves isolating sounds and identifying them with meaning, retaining those first conclusions while isolating new sounds and assigning to them yet more meaning, at the same time adding meaning to the existing stock of words.

'We do know that the amount of exposure to language that kids have really matters,' Christiansen told me. The more speech that a child hears, the greater and earlier his chance of mastering it.

This needs to be understood in a particular way. Ambient talking seems to do little or nothing for babies and toddlers. If two adults stand around talking to one another, the baby in the bassinet is likely to tune them out.

What helps babies most is having people speak and read with them, in a responsive way. As one academic observed, 'If hearing language was all that mattered, children could be set in front of a television or radio to learn their native tongue.' They can't.

Babies don't learn from machines - at least not yet. What millennia of human experience and innumerable modern studies do show is that they learn from us. They need us to pay attention to them, to talk and play and read with them.

How sharing baby books makes a huge difference

Illustration: Kate Alizadeh

One reason baby books are so helpful might seem to be so obvious as to scarce merit mentioning: books contain words. (Well, of course they do!) But there is more to it than that.

Board books in general do not have a great number of words. Often there's no more than one word to a page, or no words at all, just pictures. It's in the interaction with the book that the word-magic happens.

Take, for example, the experience of being read Peepo! by Janet and Allan Ahlberg. The child on the lap will hear the language of the printed text, read by an adult, but also the talking that results from the sight of the pictures.

Coming to an illustration of the baby in his high chair, a parent might naturally make a few remarks about the scene: 'What's that baby doing? Is he eating his breakfast? Look, he has a spoon in his mouth.' This sort of chatter is a huge help to babies as they begin to pick up the rhythms of vernacular speech, which, as Dante observed, is everyone's first language.

How books can help to develop empathy

Illustration: Erika Meza

The personalities and conflicts that children encounter in storybooks can intensify their emotional awareness with amazing rapidity. A 2015 programme in the north of England sent trained readers into nurseries that cared for 2-year-olds in impoverished areas in and around Liverpool. Over the course of just 15 weeks, teachers and project workers involved in the scheme reported improvements in the children's language abilities and increased responsiveness to books and storytelling. They also saw, among the parents of these kids, greater enthusiasm and confidence about shared reading.

In the toddlers, contact with the characters in picture books seemed to stir new depths of empathy. As one observer reported: 'I was reading Solomon Crocodile [by Catherine Rayner] and as the story goes, Solomon annoys all the animals in the river so that they shout "Go away!" at him. When I got to the page with the hippo and his wide-open mouth, as he roars "GO AWAY" at Solomon, 2-year old Finn made a pushing action with his hands towards the book and shouted, "Go away, go away!" at the hippo.'

Little Finn had taken Solomon Crocodile's side and, in a surge of fellow feeling, wanted to defend him against the rude and shouting hippo.

As Dilys Evans writes in Show and Tell, a book about illustration for young readers, picture books 'are often the first place children discover poetry and art, honour and loyalty, right and wrong, sadness and hope'.

And it's true: a child sitting on a lap at home or in the friendly security of circle time at school or at the library has a chance to witness the emotions of others and experiment with his own without consequence.

He can try out big ideas, find consolation for his secret worries, and risk a glimpse at what scares him.

The Enchanted Hour: The Miraculous Power of Reading Aloud in the Age of Distraction by Meghan Cox Gurdon is out now, published by Piatkus.

Discover our tips for reading aloud

Topics: Board book, Picture book, Early learning, Features

Add a comment