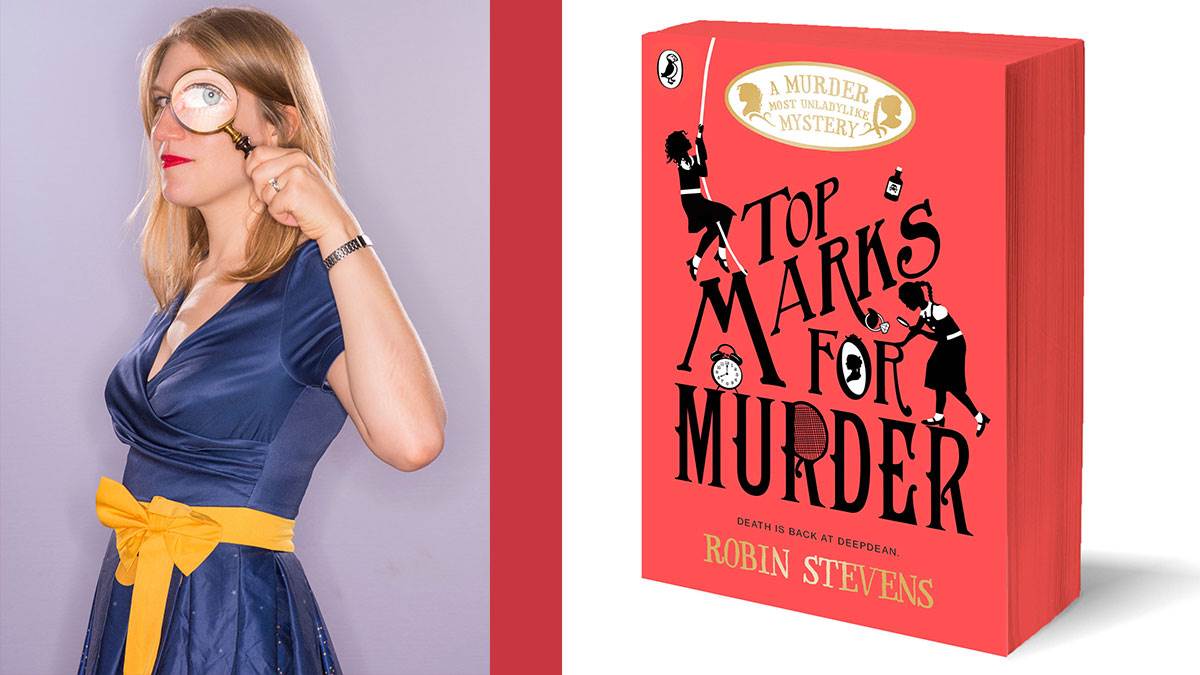

Robin Stevens, author of Murder Most Unladylike, on how her main character Daisy is coming out as gay

Published on: 15 Awst 2019 Author: Robin Stevens

Robin Stevens' incredibly successful middle grade series has always aimed to mirror real life and the diverse world around us. Here's why it is so important that books like hers celebrate LGBTQ+ characters in children's books.

In some ways, it’s easy to say where my character Daisy Wells came from. She had her start in the self-centred, sharp-tongued Gwendolen Chant from Charmed Life, the vain Gwendoline Lacy from Malory Towers (there are a lot of Gwendolen/ines in Daisy’s DNA), spirited Nancy from Swallows and Amazons and Susan from Narnia, who shouldn’t have had to give up adventuring just because she discovered fashion.

But there’s one way in which she differs from each of these characters – and, in fact, every character I ever came across in children’s books when I was growing up: Daisy is a girl who falls in love with other girls.

All of the rules were wrong

As a child, I realised quite early on that people in books must operate on quite different rules to the people I met in real life. In my real life, after all, I went to school with children who were Black, East Asian and South Asian, while everyone in school stories had blond hair and blue eyes. In real life, there were also gay people, while in books the concept had apparently not been invented. It took me until I read my first Sarah Waters book, aged 13, to discover (with a sense of utter astonishment) that you were allowed to write stories where girls fell in love with each other.

That day I began to realise that all of the rules I’d learned about who could be in books, and what books could be about, were wrong.

It’s taken me a long time to really understand why my friends and I were lied to (Section 28, one of the coldest, wickedest laws to have been passed in the UK in the last 50 years), and even longer to decide what to do about it. Old habits die hard, and even when you know the rules you’ve been taught are wrong, it’s difficult to push past the invisible barrier in your head. When I wrote Murder Most Unladylike in 2010, even hinting at Miss Bell’s bisexuality felt transgressive, but I wrote it (in a children’s book! A LGBTQ+ person in a children’s book!) and the world didn’t cave in.

So I kept going, working to tell stories about LGBTQ+ as well as straight characters. Some of the suspects in Jolly Foul Play are lesbians. Bertie, Daisy’s brother, is in a gay relationship in Mistletoe and Murder. Just after it had been published, a child wrote to me to ask when Bertie and his boyfriend were going to get married, and I knew I must have done something right: their letter simply assumed that the characters in my book would behave like the people they knew about in real life.

'My book finally mirrors their real lives'

In the seventh Murder Most Unladylike mystery, Death in the Spotlight, I finally felt ready to be clear about something that I’ve known for years: that Daisy likes girls, not boys. Daisy’s coming out to her best friend and fellow detective Hazel was an incredibly emotional scene for me to write. I wanted to show that Daisy is still the same stubborn, haughty, fiercely self-confident girl we have all loved (and been annoyed by) for seven books. I wanted to show that Daisy’s crush on Martita is just the same as Hazel’s crush on Alexander.

I wanted, once and for all, to show my readers what I was never shown: that children can be LGBTQ+, and that LGBTQ+ people can be the heroes of stories, just as they are the heroes of their own stories in real life.

It's very telling that the only pushback I’ve received has been from adults who, like me, were raised on a diet of entirely straight children’s books. They worry that LGBTQ+ identities are intrinsically adult, that the very notion of queerness is too mature for children to understand. They’re afraid that children will be afraid – which, like so many adult fears where children are concerned, is comically unconnected to reality.

The children who read my books have been utterly united in their joy at discovering that Daisy is a lesbian. Either they see themselves in her, or they see their friends, or their parents. What I’ve written in my book finally mirrors their real lives, and that reflected validation matters to them.

Filling in the gaps in stories

Writing Daisy’s coming out, and seeing the responses to it, has reinforced how important I feel it is to write stories about the people I see around me. I can’t go back in time and fix the gaps in my own childhood books, of course, but what I can do is work to create stories where those gaps are filled in.

There’s still a lot more work to do – for many children, Daisy is still the first LGBTQ+ main character they’ve ever seen in a book – but I’m thrilled that they don’t have to wait for YA or even adult fiction in the way I did.

LGBTQ+ characters belong in children’s books simply because children are LGBTQ+ – it’s time that we work to not only accept that, but tell stories that celebrate it.

Add a comment