Dragons and rabbit pie: Should we be scared of danger in picture books?

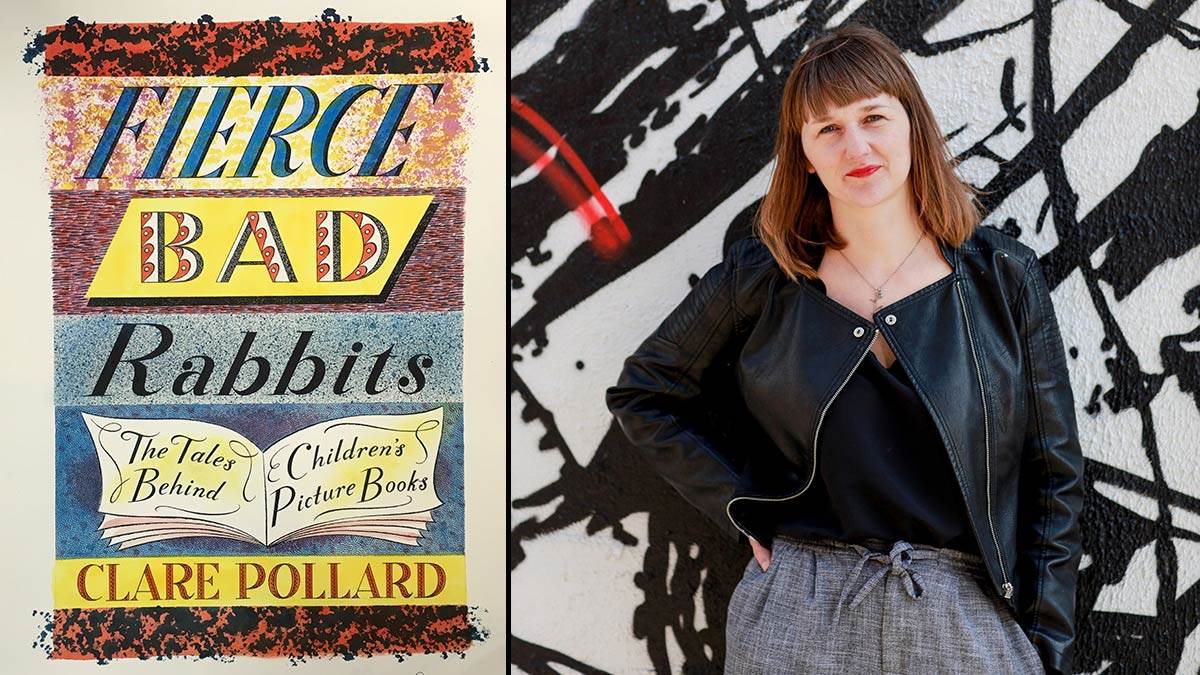

Published on: 15 Awst 2019 Author: Clare Pollard

Author Clare Pollard - whose new book Fierce Bad Rabbits takes readers on a journey through the history of picture books - explains how scary stories could actually teach little ones some important lessons...

Whilst writing Fierce Bad Rabbits: The Tales Behind Children's Picture Books, I realised that picture books have a curious relationship with danger.

When a child is sat on our knee, we often reach for a book that is cosy and comforting. We want them to feel beloved and safe. We don't want to make the child afraid, or give them nightmares.

I don't have the stomach to open certain books at bedtime - for the death of Babar's mother, or Maurice Sendak's Outside Over There, where the goblins abduct a baby and replace it with one 'made all of ice'.

The fear of imitation

There have also always been concerns about art inspiring mimicry. Plato banned poets from his Republic for corrupting youth. Violent video games, this argument goes, might make our children violent; monstrous characters make our children do something monstrous.

Many medics have written about the regularity of superhero‐related injuries in paediatrics. For a while, my small son loved to slip the straps of his buggy; leap from cots; wriggle his way out of highchairs. I toyed with the idea of writing a picture book about a tiny escapologist called Houdinki. But would it be irresponsible? Would I be encouraging other babies to attempt similar death-defying feats?

There are various cases historically of picture books being censored or altered because of the fear children might imitate characters. There were complaints that in Judith Kerr's The Tiger who Came to Tea, the Tiger pours hot tea directly into his mouth from the teapot, setting a dangerous example.

One of the most amusing anecdotes about Where the Wild Things Are is Maurice Sendak's recollection of a fight with his safety-conscious publisher, who wanted to change the dinner from 'hot' to 'warm' at the end of the book.

'It was going to burn the kid,' Sendak recalled. 'I couldn't believe it. But it turned into a real world war... Just trying to convey how dopey "warm" sounded. Unemotional. Undramatic. Everything about that book is "hot".'

There was also concern that children might mimic Max's unruly behaviour. Recently, there were complaints about the smoking in Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler's The Scarecrow's Wedding ('Why on earth would a children's book contain even the idea of smoking?' wrote one Amazon reviewer. 'Disgusting! It should be removed from sale.')

The life lessons in children's books

We like to use picture books to teach children safe behaviours - 'picture-book medicine', as Julia Donaldson puts it.

On a basic level, a character like Lucy Cousins' Maisy Mouse can teach our children health and safety - to wash their hands after the toilet, that 'when the signal goes green it's safe to cross', to hold on tight to the pole on the busy underground train.

Sometimes, though, representing danger might also be useful. In many folktale traditions, monsters serve the purpose of frightening children away from dangerous situations.

In Iceland, elves and trolls inhabit hills and boulders, preventing children from wandering away from their homes. In Nigeria, children are warned that 'Mommy Water' might drag you into the river or lake, whilst in England it is 'Ginny Greenteeth'.

In literature, Dr Heinrich Hoffmann's Der Struwwelpeter includes the tale of Harriet, who plays with matches and is burnt to death; Beatrix Potter's The Tale of Peter Rabbit teaches us that to steal or venture onto private property is dangerous; Hilaire Belloc's Henry King puts bits of string in his mouth and is 'early cut off in Dreadful agonies'.

Many books warn of the danger of strange adults, usually in the guise of witches who lure you with sweets (Hansel and Gretel) or creatures such as wolves or foxes (Potter's eerily hospitable Mr Tod).

One of the most horrifying images in a recent picture book is, for me, in Malala's Magic Pencil by Malala Yousafzai, illustrated by Kerascoët. In it Malala, an activist who at 15 was shot by a masked Taliban gunman on a bus, tells of how when she was younger she wanted a magic pencil – one that could erase the stink of refuse or conjure up a football for her to play with.

The book contains an image of men who stalk the streets carrying weapons, aiming to prevent girls from attending school. It startles me because they are not myth or beast, but simply men.

How do we explain such pictures to a four-year-old? Should we represent such real dangers, or protect our children from this knowledge?

One book that divides parents is Dr Seuss' The Lorax, which shows, through the Once-ler's polluting Thneed factory, how capitalism's obsession with growth can devastate a landscape, leaving only a 'sour-and-slow' wasteland.

It is so bleak that environmental activist Naomi Klein, author of This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate, has described how she read The Lorax to her two-year-old son, Toma, 'watched the terror cross his face' and decided, 'No, this is completely wrong.' An understandable reaction, but can we teach our children to live more lightly in the world without showing them the very real outcomes of human greed and carelessness?

Stories are powerful because they expose the link between action and consequence.

Many would agree with Shirley Hughes, writer and illustrator of such classics as Dogger and the Alfie books, when she says: 'I don't think you should inflict this stuff on young children, you've got to give them the idea that the world is a pretty nice place and it's very interesting rather more than to watch out in case something awful happens - that's for later.'

But picture book writers and illustrators keep on finding ways to explore those awful things – to confront our monsters through allegory or fairy tale; dragons and rabbit pie.

Topics: Picture book, Fear, Monsters, Features

Add a comment